Under pressure: ETHS students adjust to in-person school

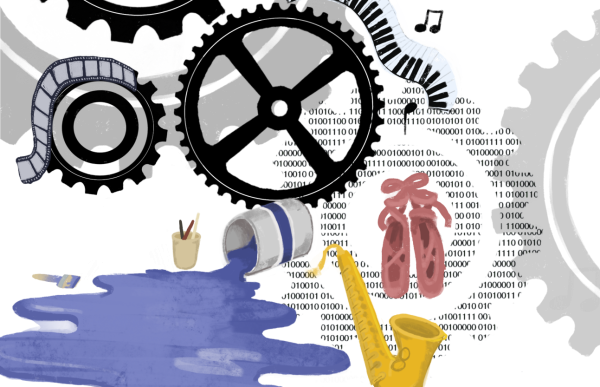

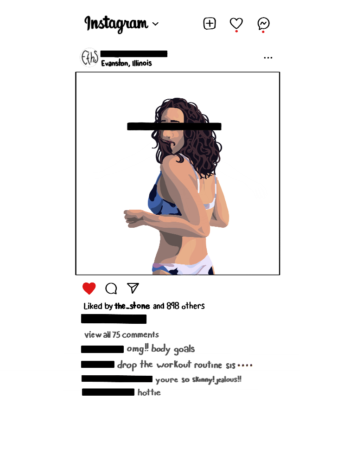

Illustration by Sabrina Barnes

As students return fully in-person for the first time since March 2020, students work to adjust to their busy schedules.

The impact of a lost year

On Aug. 16, the doors of ETHS opened to a crowd of students awaiting busy hallways, friendly teachers and rows of desks. Two years ago, this picture could have evoked a multitude of emotions, but above all: normalcy. Now, these various components that complete a “normal” school day seem foreign.

A year prior, the first day of school took on an entirely different visual. Instead of doors, students entered Zoom waiting rooms; instead of hallways, students remained in the familiarity of their homes, and rows of desks were replaced with rows of black screens.

“At home, I would like to sit on the couch or in my bed with my laptop, and I [would] have food and my phone with me, so it’s kind of a rude awakening—coming back to regular school,” senior Sonja Wagner explains. “But I feel like it’s needed because it’s time to come back to the real world and realize that in college and after high school, we’re not [going to] be able to just sit in our beds on our phones during class; we have to actually pay attention.”

Wagner emphasizes a crucial theme derived from returning to school: adjustment. However, preceding adjustment, acknowledgment is required.

“I recognize that students are not going to have the same background in math that they have [had] in previous years; I’m just trying to be more aware of that, and [I have] definitely slowed things down in all of my classes compared to previous years,” math teacher Avani Khandhar says. “I anticipate that, as we get into the material, students are going to have holes in their knowledge that I’m going to have to take time to kind of fill in those gaps. In my geometry classes, I’m taking the algebra really, really slow because I know that that’s what they did remotely.”

Taking into consideration the various effects that the pandemic could have had on students is the first step in helping students regain skills they may have lost. While content-related comprehension is a significant factor of education that may have been harmed by remote learning, social skills, including collaboration and participation, can be seen as equally as important and, potentially, equally as lost.

“I know there’s some people … [who] didn’t go out at all; [they] didn’t have any contact with anybody else, except for their immediate family or their immediate pod; even just the step of sitting next to somebody that they don’t know is huge. There’s an emotional aspect to that, there’s a psychological aspect of that, that has to be recognized; it has to be appreciated and valued,” says French teacher Ashlee Cummings. “I’m certain that there are students out there that are having a harder time than they would have had in years past, just because of the time away.”

While keeping these losses from remote learning in mind, students may feel unprepared for an entire year of in-person instruction.

“I do not feel prepared for this year at all. I feel like last year was kind of a joke of [a] year [and] that this year is gonna be a lot more difficult. I’m hoping that [teachers] ease us into it a bit more, but it doesn’t seem like that’s how it’s gonna be,” Wagner voices.

Taking into consideration the energy level that is required to withstand a fully functioning school schedule, junior Kelsey Blickenstaff explains her sense of dread entering the school year.

“I was like, ‘No, I’m not ready.’ I have to choose an outfit every day, [and] just be prepared mentally and emotionally to talk to people and be social. You can’t just be having a bad day, turn your camera off, [and] go to sleep. No, you have to be there, even if you’re exhausted.”

The addition of the new block schedule also adds another layer of unfamiliarity and potential challenges for students. Students now have up to four blocks of 85-minute classes a day, with class schedules alternating every other day, whereas students in previous years dealt with eight class periods for 42-minute periods every day. This schedule can alter classes’ workload, content, and how long students have to focus on the material they are being taught.

“I definitely feel more overwhelmed and stressed. So far, I feel like the block schedule is working for me, but I know it’s not working for a lot of students. I think it’s probably because I have a lot of really great teachers, so I’m actually able to engage, and I think engagement in the block schedule will really just depend on how the teacher teaches their class. If the teacher is really great, it’ll work great; if the teachers aren’t teaching great, it won’t work great,” explains Wagner.

Not all students have similar opinions or experiences with the block schedule.

“I do not like the block very much, but I’m definitely getting used to it. It’s definitely not as bad as I thought it was gonna be. The first few days were chaotic. No one knew what they were doing, but now, I kind of like it, because you don’t have to bring everything to school every day … It’s so heavy if you do,” Blickenstaff says.

While some students appear to be adapting to the length and frequency of classes, others have still found it burdensome compared to the schedule from past years.

“[The blocks are] too long and having AP Physics [as the] last period of the day, every day is really exhausting. It’s 85 minutes of hard science. You want to get up and move around. Some teachers let you do that, though; you have a break. They let you go out into the hall and do some work, but some teachers just make you sit in the classroom, [and] your back starts to hurt. You’re like ‘Ouch, yeah, why am I doing this?’” says Blickenstaff.

While students may still be adjusting to the block schedule, teachers have expressed their appreciation for the longer classes. By allowing teachers to have more time at once with their students, it opens opportunities for teachers and students to create stronger connections— with the content and with each other.

“85 minutes can be a really long time, but I just think you can get so much more out of the 85 minutes. You cannot have 42 minutes each day, because every day you have to check in with the students and every day you have to kind of debrief with students. If you are cutting down that time, you’re getting so much more educational time; it is giving you a better chance to actually bond with the people around you,” history teacher DeAnna Duffy says.

In regards to the mixed opinions about block scheduling and the loss of various skills during remote learning, it may feel as though this school year is crowded with obstacles. However, teachers still feel hopeful about in-person instruction going forward.

“I’ve already had students express that to me, [saying] like, ‘Hey, I’m learning a lot more being in the classroom compared to being on zoom,'” says Khandhar. “I know that I’ve already experienced students participating, and I anticipate that both participation and comprehension will be greater than they were last year.”

In order to keep this hope afloat, teachers emphasize the importance of demonstrating patience and grace. In light of all the challenges attached to this school year, an emphasis on self-care and personal well-being should be enforced.

Duffy concludes, “I’m just trying to be incredibly understanding this year because we came back, but we’re still in a pandemic … It’s a really hard transition, [and I’m] just trying to be understanding of kids and allowing them to put their emotional health first rather than my curriculum.”

Outside of the classroom looking in

In the time that has passed since ETHS’ in-person abeyance; extracurriculars have been modified to comply with COVID-19 restrictions. Students’ idea of after-school “normalcy” existed behind computer screens and the thought of meeting in-person seemed inconceivable.

Now, as ETHS opens its doors to faces new and old, the transition from remote to fully in-person, adjoined with the renewing of extracurriculars, echoes a sense of familiarity of life before the pandemic. Despite in-person school being well-received as a step towards normalcy, students are feeling overwhelmed in trying to balance rigorous coursework with after-school activities.

“Honestly, the homework has been really detrimental to my mental health recently, because I have so many extracurriculars,” says junior Claudia Marter. “I feel like a lot of people have clubs and/or go to work, [so] by the time they come home, it’s really late at night [and they] may have to stay up really late to get all their work done when they could be sleeping.”

Marter’s experience emulates the stress, common amongst high schoolers, that comes with a busy schedule and hefty workload. The return of in-person schooling accentuates the mounting pressure to achieve academic greatness and engagement in non-scholastic activities. With upperclassmen rushing to prepare for post-secondary plans, a participatory scramble has begun.

“I definitely feel like there has been more pressure to join extracurriculars, especially since it was so hard to join them last year,” says Marter. “[Since we’re] close to senior year, it feels like it would look better on college applications, but, at the same time, it feels like I don’t have enough time because of how stressful academics have been.”

The return to in-person activities hasn’t been all bad, though. While stress has undoubtedly risen, motivation has as well.

“When we were online, I did not want to do anything,” recalls junior Tyler Alexander. “Being in front of a computer screen trying to learn over a year’s worth of material made those many, many months of school so boring for me. This affected my interest in extracurriculars too. I was drained from doing school online, and there just wasn’t much energy left for other things, I didn’t have any motivation to participate. Now, being back in person, I feel much better in that regard— much more engaged and ready to be involved.”

The upheaval has become second nature to students during COVID-19. It can be difficult to even recall what an education was like before masks, Zooms and isolation. Now, as schools across the country work their way towards normalcy, students experience a shock in their schedule and class experience.

“I think the difference in workload is astronomical,” Marter says. “Honestly, last year I got maybe one piece of homework every two days for every single one of my classes. Then, this year, [I have] at least one thing to do for all of my classes, [which is] due like every single day. Also, this year, I’m taking three AP classes as opposed to one, and it’s just very, very different.”

Marter is not alone in this reaction. Plenty of people, staff and students alike, cannot remember the time when such a heavy workload and busy schedule were a usual part of life.

“Of course the amount of work I have has changed,” Alexander continues. “Being back in-person, we’re trying to go back to what school used to be like, so teachers are likely to try and return to giving the same amount of assignments they did pre-COVID, if not more to make up for all the learning time we lost over the Zoom year. Junior year has a notoriously intense workload. It just feels ridiculous for a lot of kids, because of all the down time we spent during the pandemic. Going from zero to 100 is a lot harder than going from 75 to 100, like we were meant to. COVID really threw a wrench in the progression to Junior year. Instead of building up to the stress, we’re just getting thrown in.”

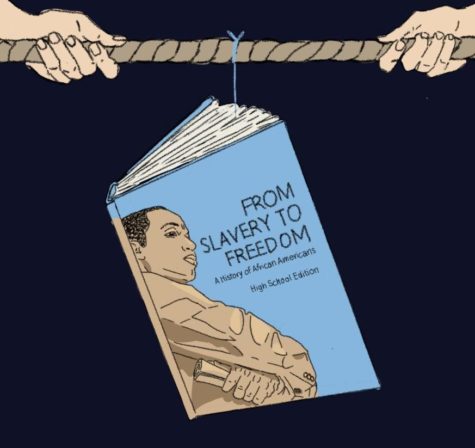

The drastic change in everyday routine and the academic burden has shifted the general outlook on extracurriculars. While most after school activities are meant to be something fun and fulfilling to be involved in, they have gradually come to be viewed by many as phrases to add to a college application. Not everyone joins these activities for the purpose of building a post-secondary resume, but many ETHS students sense the rising pressure to get involved for involvement’s sake, rather than genuine interest or passion for the subject.

As application “season” approaches, juniors and seniors are left to ponder post-secondary options, creating new pressures to appeal to them. Students are often faced with the overwhelming standard of accomplishing a “well-rounded” status, requiring thorough immersion in educational and recreational activities. This pressure breeds the misconception that indulging in an extensive amount of extracurriculars is necessary to build a strong application.

Community Service Coordinator Diana Balitaan reflects on their own experience with the application process. Despite applying to college nearly a decade ago, Balitaan reverberates the similar expectations students feel today.

“I will say that I think there was my own pressure from my parents to be involved, to do something well-rounded and to start something new, knowing that that would look good for post-secondary options … I do think that there’s this looming pressure and the idea that ‘I have to be committed to this thing for four years, even though by my last year I’m maybe not interested in it anymore,’ or thinking, ‘ have to be in a few different things because it does look good for colleges.”

Even as time goes on, the school remains largely the same. Despite the time away from the school, its physical construction hasn’t changed; just like the culture that exists. Students still feel pressure to fit into the school’s aforementioned environment. However, in this space, clubs and extracurricular activities can provide a refreshing change unlike any other.

These activities should be cherished and revered for their ability to connect even the most distant of students through passion and interest. Instead, the looming pressure to appear perfect has begun to erode the joy that once drove students to join extracurricular activities. Rather than inspiring the next generation to explore what makes them happy, ETHS culture at times can encourage these students to look elsewhere in pursuit of societal validation as opposed to personal fulfillment.

Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.