Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

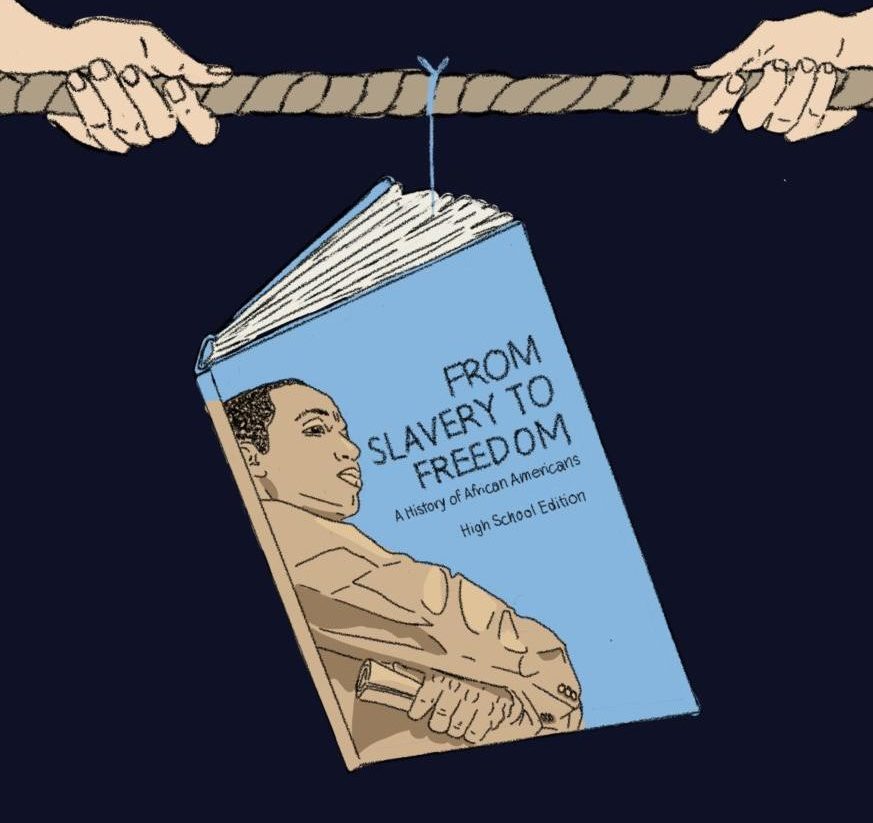

A historical tug of war

Politicians, College Board push to alter AP African American Studies course being piloted at ETHS

March 15, 2023

In 1969, then-senior Hecky Powell marched 250 students through ETHS’ Heritage Hall that runs right through the center of the building. Students from all walks of life parked outside of the Superintendent’s office, covering every inch of ground in the main lobby. They had one mission in mind: implement an African American studies course at ETHS. The following year marked the first formal teachings of Black studies within ETHS school walls.

In spite of Evanston’s historic pursuit towards progressive action, many other cities countrywide do not share a similar past. Amid a period of national civil unrest, Powell’s protest was a great triumph for ETHS and the Black community. Now, over 50 years later, new strides towards racial equity still coincide with national tension and controversy.

“We’ve had Black students here for a long time, and during my time at ETHS, we’ve had a rich history of teaching from that particular perspective—both in core courses and in electives. Of course, we still have room to grow. As educators and historians, we should always be seeking to incorporate more stories that reflect who our students are,” says History Department Chair Nicole Parker.

Evanston is currently piloting the College Board’s newly introduced AP African American Studies course (APAAS). As one of 60 schools nationwide trying this curriculum, ETHS is opening new pathways and learning opportunities for all students—Black students in particular. However, APAAS has faced significant opposition from individuals and government institutions; its implementation is sparking national discourse, harkening back to the tension surrounding race and education from decades ago.

From history onwards

It isn’t unique for ETHS to be a trailblazer for new curriculums and opportunities. In 1952, ETHS became one of seven high schools that served as a beta site for Advanced Placement (AP), meaning AP courses were piloted at ETHS prior to becoming available to all high schools.

With Evanston’s history of piloting AP courses and reputation for progression, it was a natural fit for ETHS to be included in the preliminary stages of APAAS’ curriculum.

According to the College Board, the process for crafting the APAAS course began over a decade ago, but it wasn’t until this year that the first pilot of the course made its way into high schools. Behind the development process was ETHS history teacher Dr. Kamasi Hill, who served as one of four high school teachers on the 13-person committee that worked on the formation of the APAAS curriculum. Hill has been working with the committee for over a year now, and his focus has maintained consistent: prioritizing the student perspective.

“When adults get together and create curriculum,” Hill explains, “a lot of times, the focus on students gets lost, and because the vast majority of College Board employees are college professors, many of them have never had the experience of teaching high school students.”

“This is a high school course that introduces students to college-level material. AP courses are not college courses; they’re high school courses that have college material and teach college skills, but they’re not college courses. [In] most college courses, the professors don’t have the background of pedagogically teaching students and reinforcing certain skills. They know how to lecture, they have a command of their content, but they don’t know [how to teach high schoolers],” he continues.

When adults get together and create curriculum, a lot of times, the focus on students gets lost.

— ETHS history teacher Dr. Kamasi Hill

As the sole instructor teaching the pilot AP course at ETHS, Hill prioritizes conversation and collaboration, rather than recitation, which is the philosophy of teaching that he urged the curriculum to emulate as he worked to create it.

“Let’s say we’re studying the Great Migration period of the early 1920s. A college professor will say, ‘These are the scholars that wrote about the Great Migration, these are the things that happened and this is what the long term impact was,’” Hill elaborates. “[As a high school teacher,] I will come into class, and I will say, ‘What does migration mean? What is greatness?’ . . . I would actually have a conversation inviting students to think about, on a fundamental level, what does it mean when human beings leave the place where their jobs are, where their families are, where their community is and then go somewhere else permanently?”

This year, the class consists of eight students partaking in the AP curriculum. They are learning alongside a classroom full of students in ETHS’ long-standing non-AP African American Studies Honors course. The class size of the AP pilot is not abnormal, since the class wasn’t offered to the broader student body or suggested by counselors.

“A pilot class is not part of the books. It’s not on the books, so counselors can’t sell the class. As you know, as a student when you take classes, your counselor assists in that process. There was none of that,” says Hill.

Although managing a classroom with two different levels in it comes with challenges, Hill has found a curriculum that everyone can partake in, prioritizing engagement on multiple levels within the topic.

“[The APAAS class] is interdisciplinary,” Hill explains. “One day, we may be learning about food, the next day, we may be learning about geography, the next day, we may be learning about performance and another day, we may be learning about typography of climate.”

I think it’s great to learn about my history as being an African American and having ancestors who have gone through slavery, learning about their past, and not just hardships, but how we’ve overcome those and grown over the past 100 years.

— Senior Brooke Banks, a student in APAAS

The APAAS course is for students who want to examine a broad range of ideas and their effects on African American history and culture. According to the recently released official APAAS framework constructed by the College Board for 2023-2024, there are four distinct units in the curriculum. The first unit, titled “Origins of the African Diaspora,” focuses on the history of different African nations and people, covering topics such as early West African Empires and early Africa and Global Politics. The second unit, “Freedom, Enslavement, and Resistance,” covers Atlantic Africans, the Transatlantic Slave Trade and resistance and the Civil War. The third unit, “The Practice of Freedom,” covers the history of reconstruction, “The Color Line: Black Life in the Nadir” and “The New Negro Renaissance.” The fourth unit, “Movements and Debates,” covers the Civil Rights Movement along with discussions of Black pride and diversity within the Black community.

Brooke Banks, a senior who is one of the eight students in the pilot class, has already learned a lot from this course.

“I think it’s great to learn about my history as being an African American and having ancestors who have gone through slavery, learning about their past, and not just hardships, but how we’ve overcome those and grown over the past 100 years,” says Banks.

Historically, most AP spaces have been predominantly white, which leads to an unwelcoming environment for students of color who wish to engage with AP curriculum. However, by incorporating representations of Black history and culture into AP curriculum, Black students who hope to pursue an AP course may feel less isolated.

“Unfortunately, sometimes [students] group themselves in terms of race and just feel comfortable in those spaces,” Hill states. “Most [students] would at least want some adequate representation in the class [so that] they don’t feel like they’re alone.”

Asia Daniel, a member of the African American Studies Honors course, learns alongside the APAAS students. She describes the impact that having Black voices in class can have.

“The dynamic of the class is pretty good. It’s a nice, comfortable environment, and we can all relate to each other and in a good way. From my experience in my past AP classes last year, I was in AP English, and there were Black students and me, and you can’t really relate to the material [when you’re] surrounded by other people who don’t really know [your experience with the subject]… but being in a classroom environment surrounded by people who look like you is also more comforting and nice to be in,” says Daniel.

The importance of representation in APAAS goes beyond just the class’ demographics. It carries into the content of the course, which is drastically different from any other AP class.

I think making an AP [African American Studies] class will go against the long history of Eurocentric or white courses taught by College Board or AP.

— Brooke Banks

“I think making an AP [African American Studies] class will go against the long history of Eurocentric or white courses taught by College Board or AP and make people of color feel more invited to AP spaces,” says Banks.

Although these are only the early stages of what the class will look like in future years, student feedback is already positive.

Junior Milan-Giovanni Fultz is also enrolled in the pilot this year.

“I think this new course is a pathway to a better understanding of American history and building a stronger community,” Fultz says.

The controversy

Despite the praise that the class has received from students, the curriculum has faced major backlash and pressures for change. On February 1, the College Board released its official APAAS curriculum. The new curriculum was a significant revision of the original material introduced to pilot classes in 2022. The release came less than one month after Florida Governor Ron DeSantis announced that he would ban the class from Florida high schools. This began one day after DeSantis released a plan to overhaul higher education in his state and less than two weeks after Manny Diaz Jr, Florida’s Commissioner of Education, tweeted his “concerns” about six of the topics covered in the original APAAS curriculum. His concerns included the curriculum’s discussions around intersectionality, the Movement for Black Lives, reparations and several readings implemented into the course. The Feb. 1st changes, which adhered to many of the suggestions, made by Florida officials, resulted in uproar from leftist scholars who felt that the College Board had caved to the Republican political agenda.

The outcry surrounding APAAS stems, in part, from the recent movement to ban critical race theory (CRT) from classrooms. CRT became a mainstream concept a few years ago, when conservative journalist Christopher Rufo discovered that the term was being used by legal scholars to dissect systemic racism and white supremacy in America. Rufo was able to warp the true meaning of this term and reframe it as a negative, radical race ideology employed by anti-racist activists. Since then, CRT has been a large political target for conservatives who claim that CRT is discriminatory against white people. Since CRT was introduced as a conservative talking point, it has come to represent the right’s determination not to teach any racial topics in classrooms, and DeSantis has been at the forefront.

“The woke class wants to teach kids to hate each other, rather than teaching them how to read,” DeSantis told his state’s board of education in June of 2021.

Not only has the issue of race in schools fueled many angry discussions, it has also become a tremendously effective campaign strategy. It was seen, perhaps most effectively, with the election of Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin, who won a blue state by running on the mission of protecting children from a supposed “woke agenda.”

Youngkin’s first executive order as governor was to “end the use of inherently divisive concepts, including critical race theory” in K-12 schools. However, there is no mention of CRT in any Virginia K-12 curricula.

Mirroring Youngkin’s rhetoric, DeSantis’campaign in favor of restricting education is fueled by his political motivations. It’s widely believed that the Florida governor will run for president in 2024, which explains his attempts to gain national support from conservatives. Hill notes that he views DeSantis’ censorship efforts as mere political strategy.

“He’s doing what he’s supposed to do as a conservative Republican candidate who’s trying to drum up a base of support for his candidacy,” Hill says, “because he has to run against the most popular person in the Republican Party, and that’s Donald Trump.”

In addition to DeSantis’ opposition to APAAS, he has also initiated book bans within Florida schools by establishing a law that requires all books within school libraries to be approved, and he has introduced a bill that attempts to restrict curriculums at state universities, in part by banning the teaching of gender studies. One of his most infamous policies is the Parental Rights in Education bill – labeled by liberals as the ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill – which he signed in March, 2022. The bill prohibits curricular instruction surrounding gender identity and sexual orientation “that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.”

“The ‘Don’t Say Gay’’ bill has made me, as a queer student, fear disclosing my identity to my teachers,” emphasizes Zoe Weissman, a student at a private high school in Florida. “I am scared that my school’s administration, as well as other administrations at private and charter schools, will be forced to abide with DeSantis’ education standards out of fear of repercussions.”

The ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill is a product of the broader movement to censor LGBTQ+ voices and otherwise controversial topics, restrict teachers’ ability to teach what they want and set up hotlines for parents and students to report teachers who don’t follow the rules.

The ‘Don’t Say Gay’’ bill has made me, as a queer student, fear disclosing my identity to my teachers.

— Zoe Weissman, a student at a private high school in Florida

Additionally, while lawmakers continue to craft educational policies, they often neglect the voices of those who, arguably, matter the most: students.

“I think that [censoring APAAS] can be extremely harmful, because [it’s] denying me and other people the right to know my history,” Daniels states. “It makes no sense to me. [Politicians are] empowered to think that they’re doing all [of] these good things, but they’re depriving [students] of learning important [topics]. They think that they’re helping people but they’re not; they’re setting us back even more.”

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, a professor of African American Studies and History at Northwestern University, is a nationally recognized author, activist and scholar. In 2020, she was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and in 2021, she was inducted into the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship. She addresses the nature of Republican ideas when it comes to race in the classroom.

“[Anti-CRT people] don’t want to actually talk about the substance of the issues, because it gets into things that they don’t want to address, which is the United States as a systemic, institutionally racist country,” Taylor says.

While many of the conversations about critical race theory that politicians like Youngkin and DeSantis have engaged in were unspecific and fabricated, demands for changes to the APAAS curriculum have been more particular. The controversial original outline of the class included heavily debated subjects like Black Queer Studies, intersectionality, reparations and the Movement for Black Lives. It also featured the work of controversial Black authors and activists like Angela Davis and Kimberle Crenshaw. All of these elements faced opposition from DeSantis and his political allies, and, seeing an opportunity to gain support and publicity, DeSantis made the class a central political talking point.

Parker believes that DeSantis’ agenda is ignorant and misses the purpose of APAAS.

“What I understand about this new course and Governor [DeSantis’] reaction or other people’s reaction to it, is they didn’t go deep enough to really understand what the course is all about,” Parker states.

Specifically, the New York Times reports what changes were made to the curriculum after increased pressure from Florida officials.

“The study of contemporary topics — including Black Lives Matter, incarceration, queer life and the debate over reparations — is downgraded. The subjects are no longer part of the exam, and are simply offered on a list of options for a required research project.”

For DeSantis, these changes just mean getting rid of a movement – Black Lives Matter – that he portrays as violent and anti-American. For Taylor, however, the push to censor BLM is a sign of Republican fear.

“I do think that the defining characteristic of [the protests of 2020 was that] they were multiracial. They weren’t just Black people demanding Black Lives Matter. There were tons of young white people at these protests, and I think that that scares the hell out of the right, the way that young white people have been radicalizing.”

Even within the walls of ETHS, students have sensed the same “fear” that Taylor describes.

“I don’t believe it’s harmful in any way to learn about [Black] history, and I feel like that’s the reason why [the right wing is] scared, because it’s a class focusing on Black liberation [and] our struggles,” says Banks.

A similar trend can be found in the elimination of intersectionality from the curriculum. Intersectionality is an analytical framework that teaches that discrimination across social categories like race, class and gender is all connected. The concept, which is considered a progressive framework, also failed to make the class’ final cut.

Furthermore, the term “police brutality,” which was a part of the initial curriculum, was erased by the College Board for the Feb. 1 release. In the wake of the January traffic stop and murder of Tyre Nichols, an unarmed Black man in Memphis, the curricular decision has been seen as controversial. Black households continue to grieve the Black lives lost to police brutality, with parents, brothers and cousins living in fear of who will be next. Meanwhile, conservatives point to the bravery of police and condemn those who want to expound on the harsh realities of policing in America.

Rich Lowry, the editor-in-chief of National Review, a conservative news and opinion magazine, believes that the new version of the course still teaches the most important history.

“This is the typical game of pretending that the only way to teach the history of African Americans is through the tendentious political lens favored by the Left,” Lowry writes in the New York Post. “When red states push back against critical race theory, its proponents make it sound as if students will, as a consequence, never learn about the Transatlantic slave trade, the 13th Amendment, or Frederick Douglass.”

Taylor, on the other hand, points to the trend of conservatives making themselves victims of the “woke” left.

“[Conservatives] claim that it’s the woke mob that wants to cancel everyone and wants to shut down any debate in a conversation, and, meanwhile, these people are banning books, they’re banning discussions, they’re telling you what you can say, they’re telling you what you can’t think, they’re telling you what you can talk about in the classroom, what you can’t talk about in a classroom. They’re literally micromanaging every aspect of engagement in schools, because they’re afraid of these ideas, and they’re afraid of the way that these ideas might make sense to people in ways that undermine their trust, patriotism [and] blind adherence to what it means to be an American.”

Meanwhile, the College Board has carried the weight of making determinations about what should and shouldn’t be included in the curriculum. In response to a scathing report from the New York Times that claims that the College Board was influenced by Florida politicians, the educational organization pointed to the dates that it made its revisions to the course.

“The Times argues the revisions were made in response to Florida, despite the fact that the College Board has time-stamped records of revisions from December 22, 2022,” the College Board published in a Feb. 1 statement. “The article simply ignored that the core revisions were substantially complete—including the removal of all secondary sources—by December 22, weeks before Florida’s objections were shared. The fact of the matter is that this landmark course has been shaped over years by the most eminent scholars in the field, not political influence.”

Frederick Hess, an education policy expert and political scientist, writes in Education Next that the College Board’s statement should be a reality check for leftist academics.

“There’s a good chance that the College Board is being straight when it says that most (or even all) of these changes were in the hopper before DeSantis put this on the radar a few weeks ago. If that’s the case, the fact that the College Board and DeSantis wound up in pretty much the same place—rich African American history, yes; radical academic fashion, no—should prompt plenty of reflection.”

Despite the evidence that the actions taken in Florida may not have directly influenced the final curriculum, Taylor still blames DeSantis and other conservatives for the changes. She remains disappointed and outraged by the decision to exclude these elements from the curriculum.

I think it’s important for [ETHS] to have [APAAS] because it aligns with our values and who we are. It’s the right time to talk about history, because history is being politicized.

— Superintendent Marcus Campbell

“To me, it seems fairly obvious that [the College Board] acceded to pressure from the right wing,” Taylor states. “Even if they weren’t making direct change in response to the specific comments made by Ron DeSantis [in January], the overall atmosphere that has been whipped up by conservatives that degrades, denounces [and] dismisses African American Studies is certainly a part of the atmosphere that the College Board is responding to.”

While ETHS teaches the course with pride, the debate around talking about race in schools is much closer to home than many realize. At New Trier High School, which is located just a few miles north of Evanston, there have been heated discussions over race in curriculum for years. In 2017, the New Trier school board announced that they’d be holding a “Seminar Day” on topics relating to race, such as racial microaggressions and implicit biases. The guest speakers were going to include authors Colson Whitehead and Andrew Aydin, who have both received prestigious awards for their works relating to race. This seminar faced immediate backlash, with a group called “The Parents of New Trier” forming to protest the seminar. They stated that the idea for the seminar was “unbalanced and divisive” and didn’t include enough conservative perspectives. They also argued that language like “systemic racism” was biased and even bigoted. This was long before critical race theory became mainstream, but it highlights the significance of ETHS’ decision to pilot APAAS.

“I think it’s important for [ETHS] to have [APAAS] because it aligns with our values and who we are,” Superintendent Marcus Campbell explains. “But broadly speaking, in a time where people are not wanting to talk about history for what it is and for what it was, wanting to erase it—there are states that are banning the discussion of it—[APAAS] is critically important right now for students across the country. I’m glad the College Board is [committing] to understand history as it occurred, not to erase and minimize all of the trauma from the past. This [course] has a bearing on the inequities that we see, socially, today. It’s the right time to talk about history, because history is being politicized . . . certain kinds of facts are being erased for political reasons; it’s just the right time to talk about it.”

Amidst controversy, ETHS remains unwavering in its mission towards equity, which includes not only teaching content in the name of racial justice but also understanding the deeper importance beneath the curricula and dialect surrounding African American studies.

“[Black history] is significant because it helps us to understand who we are today. We don’t really know who we are unless we know where we’ve been, and that means collectively . . . everybody. Black history is U.S. history. It’s important for us to understand our local context, our present context and how we continue to move forward so that we don’t repeat some of those atrocities in the past,” Campbell concludes.

Zoe Kaufman and Paula Hlava contributed to this article.