Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

Piling up: peer pressure pervades teenage experience

Students explore the 'smaller details' of peer pressure that adults too frequently ignore

April 20, 2023

Teens in the ‘80s and ‘90s may be eerily familiar with the infamous catchphrase: “Just Say No.” On Sept. 14, 1986, former First Lady Nancy Reagan launched this widespread campaign in a nationwide broadcast where she stated, “Long ago in Oakland, California, I was asked by a group of children what to do if they were offered drugs, and I answered, ‘Just say no!’”

Decades later, a similar message remains instilled in teenagers. Between conversations with parents and lectures in health classes, the be-all and end-all solution to avoiding risky behavior in high school is to just say no. However, this seemingly simple act is often much harder in practice, because the “Just Say No” rhetoric fails to investigate why students so commonly find themselves saying yes in situations where they otherwise might not have.

Researchers and educators often boil this phenomenon down to two words: peer pressure, which occurs when the actions of others in a particular age group dictate the decision making of an individual in the same age group. Conversations surrounding peer pressure are expansive and, most commonly, geared towards adolescents. However, the demographic that tends to lead these discussions the most—adults—frequently oversimplify this issue and neglect the intricacies of peer pressure.

As sophomore Gwendolyn Dinsmore put it, educators “are missing the smaller details” on peer pressure.

The textbook example that nearly every high schooler has been warned of is forced substance use.

“Adults teach peer pressure as other kids offering you drugs in the bathroom or at a party and forcing you to do them, but I think that’s really inaccurate,” senior Amelia Myers said.

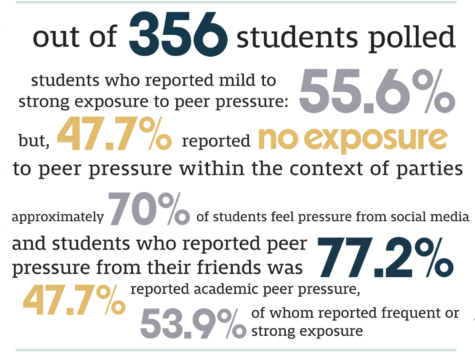

In a survey conducted by The Evanstonian, 356 current ETHS students were asked to rank their overall exposure to peer pressure in high school on a scale of one to five, with one indicating little to no exposure and five indicating strong exposure. Despite 56 percent of students ranking their exposure at three or higher, only 22 percent of students reported frequent to strong exposure within the context of parties.

Despite the personalized experiences of these students, one common thread exists between their stories: adults can’t seem to understand. While certain elements of teenage life have stayed the same from when Nancy Reagan preached “Just say no,” as high schoolers born in the digital age, there is a pressure to achieve academic excellence, maintain an enviable social media presence and develop strong friendships.

Fitting In

The habit of associating peer pressure with substance use isn’t necessarily off base. However, students reported the manifestation of this pressure is less so external and more so internal. In other words, the example of “If you don’t take this shot, you’re not cool,” doesn’t really exist. However, the notion of, “If I don’t drink when all of my friends are, I won’t have as much fun,” is very much real. A blanket term for this experience is FOMO: fear of missing out.

“I don’t experience much [peer pressure]. I think the feeling of pressure I have more [of] is from FOMO and not wanting to miss out on what my friends are doing,” senior Maya Cooper said.

Oftentimes, this line of thinking leads teenagers to partake in a variety of activities, drugs included.

“When it was warm out, [my friends and I] were at the beach, and we saw other people that we were cool with . . . We were out by Clark Beach, by the picnic tables and the trees, and [they told me] something along the lines of, ‘You can’t be in the smoke circle unless you take a hit,’ and I was like, ‘Sure,’ and I just totally faked it; I just did not want to partake,” senior Ethan Cummings said.

Despite Cummings’ blatant exposure to the pressure to participate in something he wasn’t interested in, he also noted that he rarely feels peer pressure.

“Around here, I feel like people are really good about setting boundaries. I actually haven’t been peer pressured all that much; if someone tries to offer me something . . . usually they’ll back off [and] respect my opinions . . . Most people have been very good about respecting boundaries around here, and I’m thankful for that.”

Cummings’ experience highlights the root of FOMO. Would his friends have tormented or ostracized him had he chosen to not participate? Probably not. But when an individual chooses to exclude themselves from an activity that everyone else around them is doing, it can be isolating, whether the people intend to make them feel bad or not.

“I’ve never felt pressure to drink, party, etcetera, at least for me. But there is a pressure to always be hanging out with people, and I think there’s this general sense of FOMO [that] one can get [towards] participating in things like football games, certain senior events or even social media,” senior Heath Grossman said.

Social media is another subtle force that acts as a vehicle for peer pressure. The risks of social media for adolescents are often attributed to cyber-bullying and stranger danger, which are both serious issues in their own rights. However, a common risk that frequently goes unidentified is the effect of FOMO. In a world of constant and widespread connection, access to social media has accelerated teenagers’ desire to feel a sense of belonging, enabling them to engage in a variety of risk behaviors. According to The Evanstonian survey, 70 percent of students experienced some degree of exposure to peer pressure from social media.

“I think that social media also amplifies that sort of pressure [to gain certain experiences], because a lot of things that people say that they’ve done on social media, they’re like, ‘Oh, I did this when I was 14 [or] 15.’ I’m taking in all of that information, without knowing how much of it is true. But just because I see these things online, I feel that I need to partake in that in order to be a normal teenager,” sophomore Briana Erving said.

Not only is there a pressure to align with the experiences of peers on social media, but there is also an, oftentimes internal, push to maintain a desirable social media presence, which may include crafting a virtual appearance that boasts a fun or well-accomplished livelihood. This can vary from sharing videos of parties to posting photos of prestigious achievements, and both hold influence in different ways.

“Social media creates a lot of pressure without really meaning to. Seeing people post pictures of a party or a vacation they’re on or doing anything with their friends, [by] seeing that, you feel more pressure to do [those] things,” Cooper said. “When people post about or brag about how much fun they had, it does feel like a form of pressure, like [you think] ‘Oh, now I need to go do this.’”

On the other hand, Grossman detailed the academic pressure from social media, referencing the ETHS seniors Instagram account, which allows students to share their post-graduation plans. ETHS students have run a similar account for years, and many other high schools nationwide use the same model. Although students tend to engage with the account, it can also have an intimidating effect. Every year, ETHS sends several students off to Ivy League schools and other highly prestigious institutions, and with the age of social media, for lack of better words, everyone knows where everyone is going. This can be positive for students who take pride in their accomplishments, but it can also leave other students feeling insecure in regards to their post-secondary plans.

“I was obviously swayed by the system to [want to] go to an Ivy League school,” Cummings said, who shared a story of a neighbor who openly and persistently strived to go to Princeton University, and in turn, Cummings took on that desire as well.

A lot more peer pressure has been in an academic setting [than a party setting]. Especially here at ETHS, [there’s] peer pressure to be participating in a bunch of student [extracurricular] activities and [engage in] academic competitiveness that sometimes surrounds grades.

— Senior Heath Grossman

As a college town of the internationally respected Northwestern University, Evanston has established a “college or nothing” culture, as Grossman puts it. Meaning, students frequently feel pressured to attend a four-year university, as peers, teachers and families often make that out to be the only option for success, and as a result, students feel obligated to enlist in academically competitive course loads.

The Evanstonian survey found that 71 percent of students experience some level of exposure to peer pressure in regards to academics, 54 percent of whom reported either frequent or strong exposure.

“A lot more peer pressure has been in an academic setting [than a party setting]. Especially here at ETHS, [there’s] peer pressure to be participating in a bunch of student [extracurricular] activities and [engage in] academic competitiveness that sometimes surrounds grades,” Grossman said. “[There’s] definitely peer pressure involved in the world outside of parties.”

But that academic pressure that many students resonate with isn’t inherently bad. In Grossman’s experience, he applied to be a student ambassador his sophomore year after his friends all encouraged him to do it. He explained that he wouldn’t have otherwise joined, and initially, he didn’t want to, but he’s continued to be a student ambassador for the remaining three years of his high school career.

“Peer pressure is not always a good thing, but also peer pressure has pushed me to do things that have led to amazing and great things that I don’t know that I would’ve been able to do without peer pressure,” Grossman said. “I don’t know if peer pressure is the right word to use, but it can definitely be seen as peer pressure to get me to participate in an activity [or] hangout with people that ends up growing into something greater.”

The term that Grossman is describing is known as peer influence. Peer pressure and peer influence are often used interchangeably, but peer pressure tends to have a more negative connotation.

“We don’t use the term peer pressure so much as peer influence,” psychologist Brett Laursen, who specializes in developmental psychology and researches the psychology of influence, said. “When we talk about peer influence, we describe changes that one child makes in their behavior or their attitude that they wouldn’t necessarily make if it weren’t for their affiliation with another [child].”

As an example, Laursen described a scenario in which an adolescent has a friend who dyes their hair and, weeks later, that adolescent chooses to dye their hair as well. “Peer pressure has this negative connotation of bad things always happening, and . . . all kinds of positive things happen as a result of peer influence, not just negative things.”

As an example, Laursen noted that peer influence can steer adolescents away from “unattractive activities” such as picking their noses or acts of vandalism or violence, and in turn, it can lead them towards “prosocial behaviors” like social activism or extracurricular involvement.

Peer pressure has this negative connotation of bad things always happening, and . . . all kinds of positive things happen as a result of peer influence, not just negative things.

— Psychologist Brett Laursen

So peer influence isn’t always bad, but it is certainly more powerful than some may think. Many teens have noticed that peer influence can affect identity and self expression.

“I’ve changed myself over the years pretty purposefully. I don’t have a problem with that change, and I think I’ve changed to be a better person; it’s really just me growing because I’m so young,” senior Charlie Plante said. “As I’ve become friends with different people and move through friend groups and move through life, I’ve definitely [felt] some pressure to assimilate to the rest of the group that [I’m] hanging out with.”

That pressure is far from isolated to Plante’s experience. According to The Evanstonian survey, 77 percent of students feel peer pressure from their friends. In fact, peers that fail to assimilate often find less satisfaction within their relationships.

“Opposites do not attract. We have a lot of research that suggests that the more differences you see in two friends, the less likely that relationship is to [survive], the more likely it is to dissolve,” Laursen said.

Even on a smaller scale, peer influence is still evident in unassuming ways.

“I used to hate flare leggings. I know that sounds so stupid, [but] now I only wear flare leggings because it’s a trend [now], and I feel like if I don’t [wear them], I’d seem weird,” Cooper said. “In the summer when things get warmer, I have to ask my friends if they’re wearing shorts so that I can [decide if I’m going to] wear shorts to school, because I don’t want to be the only one that’s left out.”

Although it may seem small, or “stupid,” these subtler effects of peer pressure can have a large impact on confidence and self image.

“Every little thing that makes you feel different or that makes you feel [like] an outsider or that makes you do something that you don’t want to do, it builds up, and you get this image of yourself and a false idea that you are the odd one out,” Cooper said.

In Dinsmore’s words, it’s “like a snowball:” as the snow rolls and rolls, the ball becomes bigger and bigger, and as the smaller effects of peer pressure pile up, the impact expands as well.

“How we talk and how we dress, that’s definitely because we want to follow the patterns of other people. We’re very habitual creatures,” Dinsmore said. “It especially relates to peer pressure because if all of your friends are doing it, why not join in? What’s the harm?”

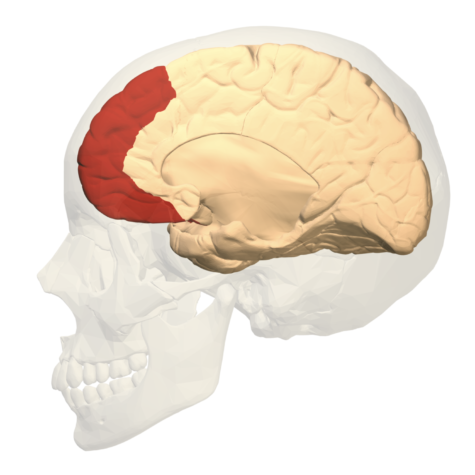

Dinsmore isn’t wrong that humankind leans towards habit, but peer influence seems to target one group in particular more than others: teenagers, and research shows that this isn’t a coincidence. In response to emotional arousal, activity in the social brain differs between adults and adolescents. Teenagers’ brains tend to activate the medial prefrontal cortex, which is the region of the brain responsible for understanding others and mirroring their behavior. Structurally, the teenage brain is wired to obsess over the thoughts and actions of others.

“Neurological maturation takes place at different levels. During early adolescence, the logical thinking part is pretty well formed, but that tends to be overridden by the presence of peers. Hot cognitions tend to override cold cognitions during early adolescence, because peers tend to stimulate these hot cognition centers, these reward centers,” Laursen said. “You might get more susceptibility to peer influence simply because there’s less taking a step back and thinking about things in a logical manner.”

Aside from just a neurological standpoint, changes in lifestyle and social routines can contribute to this phenomenon as well.

“Everybody is susceptible to peer influence across the lifespan . . . But we think that children and adolescents are particularly susceptible to [peer] influence [considering] the changes that take place from childhood to adolescence,” Laursen said. “Children are heavily supervised by adults, and their comings and goings are pretty carefully monitored. As you move into middle school, things change pretty dramatically, and suddenly you’re thrust into navigating a world that’s largely peer dominated with only superficial adult supervision. At this time, children really need to pay attention to their age mates in order to navigate these new circumstances.”

Teenage Rebellion

From cult-classics like Dazed and Confused to Joan Jett’s “Bad Reputation,” teenage rebellion has fascinated audiences for decades. American media outlets in particular have an obsession with depicting drug use and sexual activity in school, as seen in television like Euphoria. When viewers consume this content, it can lead them to commonly associate rebellion with extremes.

“Particularly in American high schools, there’s this glorification of teenage rebellion, and I think that teenage rebellion is natural, but it has the implication of sex and drugs. Rebellion can just be flourishing as a person, and not specifically sex and drugs. [But because this association is so prominent,] I think that people feel the need to engage in some of these things, or else [they feel like] they’re missing out,” Erving said.

As Erving outlined, teenagers may feel pressured to engage in risky behavior because they want to achieve a so-called “teenage experience.” This desire is proliferated when students find others who share their interest in engaging in various risky behaviors, especially substances. In fact, this impulse to explore can be the sole basis for friend groups.

There are some [friend groups] that I see where the only thing that they have in common is that they do drugs together.

— Sophomore Briana Erving

“There are some [friend groups] that I see where the only thing that they have in common is that they do drugs together . . . I think that part of it comes from a place of low self esteem, and I think that excessively doing drugs is a form of self harm, too. In fact, [it’s] a very social outlet to harm yourself, which is a little sickening, if you think about it,” Erving said.

Like Erving mentioned, friend groups can simultaneously unite and destroy teenagers. Feeling a sense of belonging is a psychological need for humans, but what happens when the exact thing that enables community damages one’s health?

This conversation is nuanced in nature, but it also can be traced to peer pressure. Largely an unconscious force, an individuals’ friend group can shape their actions and beliefs in massive ways—way more than one would expect.

According to psychologist Judith Rich Harris, childrens’ life decisions are more influenced by their genes than their parents. In her controversial novel, The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do, Harris, in response to developmental psychologist Terrie Moffits’ claim that teenagers commit crimes to be like adults, writes:

“What stopped me in my tracks was Moffitt’s explanation of this unendearing foible. ‘Delinquency,’ she said, ‘must be a social behavior that allows access to some desirable resource. I suggest that the resource is mature status, with its consequent power and privilege.’ Wait a minute! I thought. Is she saying that teenagers commit illegal acts because they want to be like adults? That can’t be right! If teenagers wanted to be like adults they wouldn’t be shoplifting nail polish from drugstores or hanging off overpasses to spray i love you li 8 A on the arch. If they really aspired to ‘mature status’ they would be doing boring adult things like sorting the laundry and figuring out their income.”

While her anecdotal justifications may appear non-scientific, she describes a social context that many resonate with.

“I‘ve definitely seen some of my friends who would stand against something for a long time, [but] then change their minds once the rest of our friends started doing it,” senior Franny Mereu said.

Tracy Van Moorlehem shares a similar experience. From navigating peer influence as a teenager to having conversations with her two daughters about the importance of individuality, Moorlehem has experienced both sides of the spectrum.

“[There have been times where] my child has been upset because I wouldn’t let them do something [that the rest of their friends were doing]. Having the conversation [with them] and asking, ‘Why are you so upset that you can’t go to this concert? I’ve never heard you listen to this music one time.’ And then [my] child saying, because everyone’s going, and I’m going to be the only one who can’t go, [leads me to respond by asking], ‘Do you think it’s best to go somewhere just because other people are doing it? Or do you think it’s best to go places that align with your interests?’ … [But I also understand] because I remember being that teenager, [and] wanting to go to that concert that I didn’t care about at all just because I was so flattered to be invited and I wanted to be friends with this particular group of people,” Moorlehem said.

If influence from friends is an established component in understanding why teenagers act the way they do, where does that leave the individual? All decisions ultimately come down to one person: ourselves.

“I have been pressured into certain things that weren’t drugs or alcohol, but I would consider myself to blame as well, because what I was talking about with low self-esteem and self-destructive behavior, that’s much of what drew me to do what could be considered ‘rebellious acts,’” Erving said.

But “rebellious acts” can also mobilize massive change. For decades, teenage rebellion has been an integral tool in petitioning the government, advocating for gender equality, and in our very own hometown, demanding tighter gun control laws.

On March 14, 2018, thousands of Evanston students walked out of school to protest gun violence following the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting. Unified by a national goal to make schools safer, ETHS students created posters, delivered moving speeches and garnered administration’s support to commit to change moving forward. When teenagers are collectively upset about something, they are able to exercise a level of agency and persistence that is uniquely powerful.

Love and Relationships

It is impossible to discuss adolescence and peer pressure without referencing sexual maturation and the complex landscapes that may come with that stage of development. From a young age, children receive a narrative on what their sexual activity should and shouldn’t look like, and this can largely impact their sexual behavior later in life, particularly during adolescence. A 2022 study found that the average age that people begin to watch pornography is 10.4 years, meaning from childhood, kids are taking in that explicit content and forming expectations about what sex should be. Depending on gender identity, this vision may look starkly different.

“Societally, I think male-identifying people are taught to be careless about sex. [On the flip side], female-identifying people are taught to think of sex as something that’s fragile and delicate, like it’s a coveted flower. [We’ve been conditioned to think that] women want to wait and men don’t care about it, and they’ll have sex with whomever. I think that’s definitely one of the biggest stereotypes that come with it,” Cooper said.

If [my] mind is saying, ‘I’m not ready,’ but all my friends have done it, I [feel compelled to think], ‘Okay, I’ll just say yes, and I’ll just do it.’

— Senior Maya Cooper

A study by Cornell University surveyed 500 women, and the results showed that a theoretical woman with over 20 sexual partners was viewed as “less competent and emotionally stable” than a woman with two partners. On the other hand, 500 men were given the same survey, but the hypothetical women were switched to men, and the man with over 20 partners was denoted as “more competent and emotionally stable” than the less sexually active man. Evidently, women tend to view sex as shameful, whereas men often view sexual activity as a point of pride, and this line of thinking can impact teenage decision making during initial sexual experimentation.

“I made a pact with one of my friends that I would not have sex until junior year of high school. When that didn’t happen, I felt like I betrayed her [and] I betrayed that idea of what I was supposed to do. It felt like I had done something out of the norm, and it felt like I was pressured to wait or not do something [that I wanted to do],” Cooper said. “It felt so weird at the time, even though it wasn’t something that should have been determined by someone other than myself.”

On the flip side, many teens experience the pressure to engage in sexual activity, which can interfere with authentic sexual wants and needs during adolescence.

“I think that it is natural for humans to want to be loved and to want to know how to show someone that they love them. I think that that’s, in the primal sense, what draws teenagers towards attraction in the first place,” Erving said. “But I think that what can [augment] this picture of teen relationships so much is the external pressure that they feel to be more experienced.”

![]() When expectations become intertwined with intimacy, an individual’s agency can often become lost in the mix. This is where peer pressure ties in with consent culture. In Cummings’ words, “peer pressure waives the consent step.” Although adolescents may not experience pressure from the people with whom they choose to be intimate, they can still feel pressured from a broader, cultural standpoint, that can sometimes be just as hard, or even harder, to say no to. This form of pressure is especially harmful for adolescents who are just beginning to learn their likes and dislikes in regards to sexuality and often lack the proper tools and confidence to vocalize their needs.

When expectations become intertwined with intimacy, an individual’s agency can often become lost in the mix. This is where peer pressure ties in with consent culture. In Cummings’ words, “peer pressure waives the consent step.” Although adolescents may not experience pressure from the people with whom they choose to be intimate, they can still feel pressured from a broader, cultural standpoint, that can sometimes be just as hard, or even harder, to say no to. This form of pressure is especially harmful for adolescents who are just beginning to learn their likes and dislikes in regards to sexuality and often lack the proper tools and confidence to vocalize their needs.

“You always learn that if you don’t want to do [something], say no to the other person. But when it’s not the other person pressuring you, [and it’s more of a societal pressure], it’s kind of like, where does that tie in? If [my] mind is saying, ‘I’m not ready,’ but all my friends have done it, and I should feel ready anyway, I [feel compelled to think], ‘Okay, I’ll just say yes, and I’ll just do it,’” Cooper said. “Sometimes, it’s not always the other person pressuring you, I think that it can also be yourself or just society in general making you want to say yes, even if you don’t want to, or making you say no even if you want to.”

Words of Wisdom

Peer pressure can affect anyone, regardless of age, but oftentimes these conversations lean towards the experiences of young people. As a result, it is essential that adults provide insight into their experiences with teenage peer pressure and how they were able to navigate around it.

When Moorlehem reflects on her internal desire to “fit in” while she was in high school, she recalls feeling a sense of dread about diverging from the norm. Now, she understands the value of having a sense of individuality.

“Particularly when you’re a young person, and you’re trying to figure out who you are, [you think a lot about] how much you have to conform. I remember being a teenager [and wondering], if I didn’t fit in, what would my life be like? I assumed it would just be terrible, [because I thought] how could [I] possibly be different from all the other students in [my] school and be happy?” Moorelehem said. “As I got older, [however], I saw many examples of people who resisted the pressure to conform and had great lives, including lives I wanted to emulate. But I think [we’re] born understanding that [we] don’t have to conform, but this innate, self doubt that most people have makes [us] think that the way to be right, to live right, to look right, to do the right things and to say the right things [is to] conform with the pressure around [us]. That leads people into all kinds of activities that can harm them.”

Like Moorelehem mentions, conformity is learned, and virtually any environment can encourage assimilation. In recent years, however, social media has transformed the landscape of peer pressure where it constantly follows teenagers.

It seems like the norm now is to do so much more work on your appearance, and that just really concerns me, [because what] kind of a message is that [sending]?

— Parent Tracy Van Moorlehem

“I grew up in the 80s in a small town in Minnesota. The world was so different then, [as] you can imagine. There were no cell phones, there was no internet and we didn’t have cable TV. My high school class was like 50 kids. So for me, peer pressure looked like somebody I had known since kindergarten suggesting I should do something. It was very personal. But today, it feels like you can’t ever get away from it. Because you’re always checking your phone, myself included, you’re checking your phone, or you’re watching TV or you’re texting with friends. There are just so many different ways now that people can be subjected to peer pressure.”

With peer pressure being so present in children’s lives, Moorlehem worries about the impact this access can have on a girl’s self-confidence.

“I worry so much about young women and all of the images they see around appearance. One thing that really stands out for me is makeup. Growing up, I would sneak out of the house and put [makeup] on at school because I wasn’t allowed to wear it, even starting in seventh or eighth grade. But now I see my daughters watch YouTube videos of these elaborate makeup rituals that are [seen as] the norm. It seems like the norm now is to do so much more work on your appearance, and that just really concerns me, [because what] kind of a message is that [sending]?”

On the other hand, social media can build community and safety. Connecting with people online gives people an opportunity to escape their current situations and create relationships with those who share common interests.

“I think one positive of social media is whoever you are, whatever you’re interested in or however you feel, you can find people out there who can speak to you and who can validate who you are and the things that you’re interested in. You could be having the worst day ever at school, and then go home and connect with people online.”

To close, Moorlehem suggested that teenagers open up to their parents or guardians about their struggles. With the help of one’s family, it can make navigating adolescents and the pressures that come with it much easier.

“As a parent, I would suggest to students or young people who are struggling to give your parents a chance . . . I know it’s hard sometimes to be honest with your parents and to let them in on things that are going on in your world, but your parents, if you think there’s a chance that they can handle hearing the details of what’s going on in your life, they might be really helpful. I think most parents really want to be [helpful]. Even though most of us are not parenting experts, we are experts in our child, we know our child, we love our child, and so I say, in doubt, give your parents a chance to help you work through peer pressure.”

Editor’s Note: The student with an asterik by their name gave quotes anonymously.

Staff Writer Milo Slevin contributed to this article.