The inner-workings of political conversations in, outside of ETHS

Discussions are prevalent throughout Evanston, and they take many forms. Whether it be a debate in English class or a heated discussion around the dinner table, ETHS students are exposed to a multitude of voices in their daily lives, which shape their perspectives on social issues and politics.

When seeing how discourse occurs amongst ETHS students within the walls of 1600 Dodge Avenue, it is vital to address the influence that the greater Evanston community, and specifically parents and guardians, have over the beliefs held by students.

Conversations at school

Departed from many other communities across the country, Evanston has long held a reputation for political progressivism, and the up-and-coming generations being raised here are seemingly no different.

Whether it be in the crowded cafeterias or the hectic halls, students are actively engaged in conversations regarding politics and social justice. However, the vast majority of these discourses occur within the classroom. Fostered by teachers, baseline curriculum and the students themselves, belief systems are molded by the discussions that take place in class.

Students’ initial introduction into civic engagement begins their sophomore year. The state-mandated Civics course equips students to cultivate and deepen their political beliefs with the ultimate goal to “encourage civic engagement and give students the skills to influence and develop the communities they’re a part of,” says History teacher Rick Cardis.

Cardis has taught AP United States History at ETHS since 2008. In 2016, “a state law passed that required public schools to teach civics. [Because] the requirements were pretty significant, we—[the history department]—made the decision to do it as a separate class [from US history],” he says.

While Civics became mandatory only a short while ago, the differences with which current students engage in curricula compared to before the course’s implementation is evident, and a clear indication that students are becoming increasingly more engaged with their communities and affirmed in their political beliefs.

“The engagement level of students is significantly higher than I’ve ever noticed or experienced in the past,” Cardis notes.

The 2016 presidential election increased awareness of social justice issues, a factor that Cardis believes directly impacted the engagement level of students. As modern egalitarian movements resisted the Trump Administration, classroom discourse flourished and more students were able to deepen their viewpoints and develop their identities as activists.

“The increase in activism that we’ve seen nationally over the last five years or so, I think largely in response to Donald Trump’s election … Black Lives Matter, and some of these national movements that have developed in the last five to six years has definitely impacted the activism that young people are engaged in. The climate crisis as well, I think, has been a big motivator,” he says.

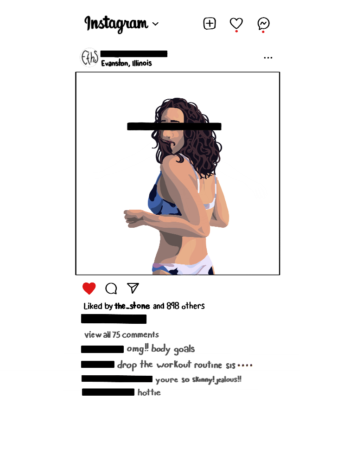

Another factor in considering the political socialization of youth is social media. With news becoming increasingly more accessible and personalized through algorithms, young people’s introduction to current events begins early.

“With social media, there’s just so many more avenues for getting information for young people. Back [when] there was cable TV, you had three news networks who distilled most of the information, which in some ways is good, because it kind of finds a middle ground to appeal to a broad audience, but at the same time, that certainly leaves out people who aren’t in the mainstream, whichever side of the discussion they’re on,” he says. “Now, [social media] is really influential, because there [are] just so many more perspectives [young people] have access to that are influencing them.”

Students that feel inclined to participate in more extensive political discussions have an option to take AP Government as an elective. Through this class, students have the ability to learn about the American legislature and participate in discourse regarding American politics.

“AP Gov [is a class] which I recommend everyone takes. … People can voice their opinions on whatever. I was with Ms. Gordon, and we specifically focused on more current events. Because of that, we would obviously talk about the politics that were going on,” senior and founder of ETHS Politics Club Madeline Matsis says.

Although AP Government is not a class where discussions regarding social justice are written into the curriculum, teachers anticipate that those conversations will arise.

“It’s definitely great to have an open forum for students to really explore, express their ideas and beliefs. But it obviously has to be a safe place where there’s a rule saying, you can’t say this, not in a sense of censorship, but hate speech and derogatory language is not accepted,” Matsis explains.

Taking an AP elective can be intimidating, but AP Government teacher Darlene Gordon wants the class to be anything but that.

“It’s so easy to have these [political and social] conversations in a vacuum [and] not really having to think about [them] in [terms of] the real world [and] what’s going on right in front of my face. The purpose and intent of my AP Government class is to study the book and prep students so they can do well on a test, but it’s also [about learning] humanity and [taking that with you when you leave] this building,” Gordon says.

Gordon sees AP Government as an opportunity for students to not only expand their knowledge, but to gain real life skills. Gordon finds issue with the fact that much of the “policing” of teachers is put onto the students. She believes that, while conversations regarding politics and social justice are important for students to have, teachers need to be more aware of what they are saying and how it might affect students.

“There’s plenty of [teachers] out there who might be teaching controversial stuff, [and] how I found out [about it is through] hearing students talk about it [in class],” says Gordon.

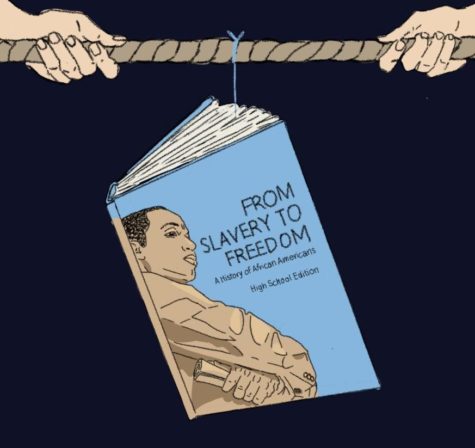

Serena Brown, a senior and founder of the ETHS Black Student Union, holds a similar viewpoint to Gordon. In class, Serena Brown observed a lacking effort from teachers to facilitate neutral political discussions.

“I’ve had classes where teachers don’t seem like they put in the effort to skew the conversation more towards a neutral ground. That makes sense. It’s very in line with their political views. And it ends up like that, and no one in the class usually complains,” she says.

In addition to Serena Brown’s comment on the direction most class conversations take, Gordon elaborates stating the onus is on teacher’s to create an environment where students feel safe and welcomed to share their opinion.

“Students shouldn’t be the police; we should be policing each other. It shouldn’t take the students. It’s on us to make us do the right thing,” Gordon emphasizes. “We should be held accountable for what we are presenting in our classroom. You may say something that you think is very benign, and that may stay with that young person for years, if not the rest of [their] life.”

There is no denying Evanston’s left-leaning identity; children who grow up in Evanston have political upbringings that are supremely unique, and yet lack diversity.

“Is it a bubble, or is it just because one viewpoint has a much louder volume and kind of silences the other viewpoint? … I don’t think there’s any issue if a certain school is one-sided or has a certain viewpoint, I think the only issue towards students is you’re not exposed to seeing and interacting and having conversations with people from the other side. The other type of bubble, right,” Math teacher Michael Bahi believes. “What that does is, as people from both sides would be guilty of this, it [causes] people to label and throw [around] stereotypes [towards] people believing in one side.”

This concept of the Evanston bubble is not a new one and shows no signs of going away any time soon. Classroom conversations can only be so educational if all of the people voice their opinions on topics that polarize the nation. The most effective way for students to strengthen their viewpoints is by defending them to the opposition, an opportunity that is largely nonexistent in ETHS and the Evanston community as a whole. Junior Sophie Brown expands on this, exploring the dialogues that prove to be scarce here.

“[The difficult conversations] are the ones that say that it’s okay to make concessions to conservatives. There’s a lot of fear behind that, which makes sense because conservatives say a lot of things that don’t match a lot of progressive ideology. But making concessions to conservatives allows you to see the larger picture; [it] allows you to not only see it, but also to engage with it and then fold it into your own conversation,” Sophie Brown says.

In Evanston, the political, social and moral divides of America are evident. They reflect in the unequal representation of viewpoints and the lack of diverse conversations occurring among students in school, leaving more conservative ETHS students feeling unsafe in expressing their opinions.

“I think it’s safe to say that as a whole we’re pretty left in political views in our school, which is not an issue at all,” Bahi says. “But I feel like, over the last year, given the circumstances … I think that there was a certain stigma, where if you had right-leaning political views, I feel like that group kind of was more silenced than the left-leaning [views].”

Juxtaposed to Bahi’s belief is Gordon, who asserts, “[At] ETHS, there’s room for everybody. Whatever your interest is, whatever your political leaning is, wherever you feel like you fit in, and you want to express yourself.”

Whether or not Evanston ever reaches a moment in time where multiple viewpoints on opposite ends of the political spectrum can coexist productively remains to be seen. While ETHS students can be categorized as having similar political beliefs, most of the world is not that way, and students will be forced to reckon with this when they leave their classrooms.

Regarding the lack of public political diversity within ETHS, Serena Brown concludes, “I think that allows us to get stuff done, I think it’s the reason because we all agree. [However] it’s also what hinders us, in the sense that we don’t always understand the full issue, and we don’t always understand where everyone’s coming from on issues. I think that it’s something that we could work on for the school.”

Conversations at home

Prior to political discussions bound by the brick walls of ETHS, students encounter these conversations within the margins of their own home. Many students’ first exposure to political dialogue stems from interacting with their family members.

“I have three kids. I have a junior, and then I have a senior in college and a sophomore in college. We have always talked about politics,” ETHS parent Sheila Loop shares.

Although students may experience overlap in the content of these conversations between school and their home, there is a significant disparity in the dynamic. With the consideration that these two spaces

provide unique qualities, communication differs between them.

“I feel like the atmosphere of having political discussions between the classroom and home are so vastly different … because in one [scenario], there’s a specific question being asked and there’s someone there mediating it who is supposed to be bipartisan,” junior Lily Straussman elaborates. “Versus a political discussion at home when … there is no bipartisanship. It’s your own personal opinions genuinely coming out, and people get really defensive.”

This defensiveness Straussman speaks of stems from a level of transparency found in household conversations that sometimes lack the structured environment of school conversations. Although household conversations may evoke defensive language, their honest qualities can leave a larger impact on the participants than possibly disingenuous school discussions.

“I feel, personally, that political conversations at home influence your political beliefs more [than conversations at school], particularly when you’re growing up and forming opinions,” Straussman shares. “A lot of the time, what your parents tell you and what they feed to you is what your baseline for political beliefs are going to be.”

Straussman highlights a key idea, universally common amongst households: the influential role of parents and guardians. In some instances, the ways in which authority figures shape their children’s beliefs may even be unintentional.

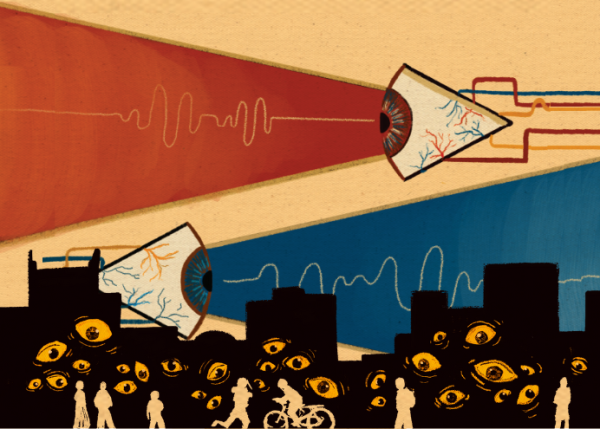

“My husband and I may watch Fox, every once in a while, [but] we don’t watch that with the kids,” NorthShore parent, Colleen MacKaimm, says. “With the kids, it’s just ABC, as the regular news, and it’s just on in the background. It’s not like we’re all sitting down just watching and analyzing the news. I just may have it on when I’m cooking or something like that.”

After interviewing several parents and students, the majority reported a similar dynamic within their household. While parents may not deliberately hand-pick the news their children absorb, they tend to hold power over which news sources are most present around the house.

“[My children] have access to all of my [primary news sources], so New York Times, Washington Post, [etc.]” Loop reveals.

Parents and students both agree that the amount of access a child has to different news affects their beliefs surrounding social issues and politics.

“I think it affects them greatly, because how could it not?” Loop explains, “Kids watch their parents, regardless of whether we believe that or not, and sometimes, it may or may not seem like they’re listening to us, but they are. They’re hearing [the news their parents listen to] in the background, and they know that [their parent is] believing that [news], and that [they’re] taking that as fact. I think that can definitely form their viewpoint.”

Junior Mayra Bazan expands on this idea.

“I’m a big believer in if you’re raised in a certain environment and receiving certain information … then you’ll start to believe that way. I think that if I was raised in a household that was really big on Fox News, I would also be really big on Fox News.”

Loop and Bazan essentially demonstrate the subconscious practice of parental authority figures controlling their children’s beliefs through filtering their news access. In addition to news biases, parents and guardians inadvertently influence their children’s political perspectives through the nature of their relationship and the power dynamic that comes with that. In some cases, this can lead to inequality when political conversations take place at home.

“I think that some of the conversations do turn hostile, and that position of power comes into play,” Bazan mentions. “I think the conversation would be more fluid, and it would be less stressful if that [leverage of power] wasn’t used as much; that argument of ‘I’m your mom’ isn’t that great when you’re trying to have a civilized conversation.”

Not only is there a disparity in power across parents and children, but an age difference can also play a significant role in explaining why different family members may approach politics in contrasting ways.

“Every now and then, we’ll have a generational difference … so we talk about it. I explain my point of view, and they explain theirs, but there’s no real tension,” Loop says.

This age gap can also help to add dimension to discussions by providing multiple perspectives on a topic. In doing so, the conversations can hold meaningful insight for both adult family members and children.

“I think it’s important for me to listen because I learn from my kids. This is a new decade—it’s 2021; when I was a kid their age, it was the 70s, so a lot has changed,” MacKaimm says. “It’s important for me to listen because they teach me. … I think it’s important for them to listen, because I have a lot of experience, and I have seen a lot more than they have.”

For students, this experience can be a useful tool as they mature and learn about different political issues. Loop recalls a specific instance in which she helped her child better understand an issue they were unfamiliar with, due to their age.

“I remember when my oldest was in ninth grade, he said something about [how] he had to debate the legalization of marijuana at the time, and I said, ‘Well, you chose pro, right?’ and he looked at me like I was crazy. He said, ‘Well, no, because it is illegal.’ I mean, this is a number of years ago, but I explained to him my viewpoint on it, and … it was like a light bulb went off. He was like, ‘Oh, oh, you’re absolutely right.’ Just [by] talking about issues that they wouldn’t know about or wouldn’t be on their radar because of their age … I’m sure I have opened their eyes.”

As students grow up, they are able to rely less on their parents for political insight and learn how to form their own opinions. Consequently, political discussions between authority figures at home and students are able to evolve and balance out in a way that helps students gain more confidence in the conversation.

“I think I’ve gotten more comfortable [talking to my parents about politics] as the years have gone by, and I’ve really solidified what my beliefs are,” Bazan explains. “I think that when I started out [in] middle school … I was a little bit more insecure, and not as certain of what I was saying and what my beliefs were. But I feel as though I am more solid on that now.”

As students continue to encounter conversations surrounding politics within their school and household, building upon their personal beliefs is a natural part of human growth. Parents and guardians, whether for worse or for better, play an essential role in shaping these beliefs. Loop concludes that a part of that role is allowing children to explore political opinions of their own.

“I think [parents should be] helping to support [their children] in creating their own political lives [and] just providing them [with] a basis. I think it would be great if more parents would lead by example, just in terms of political activism, or volunteering or showing if they’re making a donation … just treating them more [as] peers about politics and giving them [the] support to develop their own views.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.