A summer of activism: making a movement

August 17, 2020

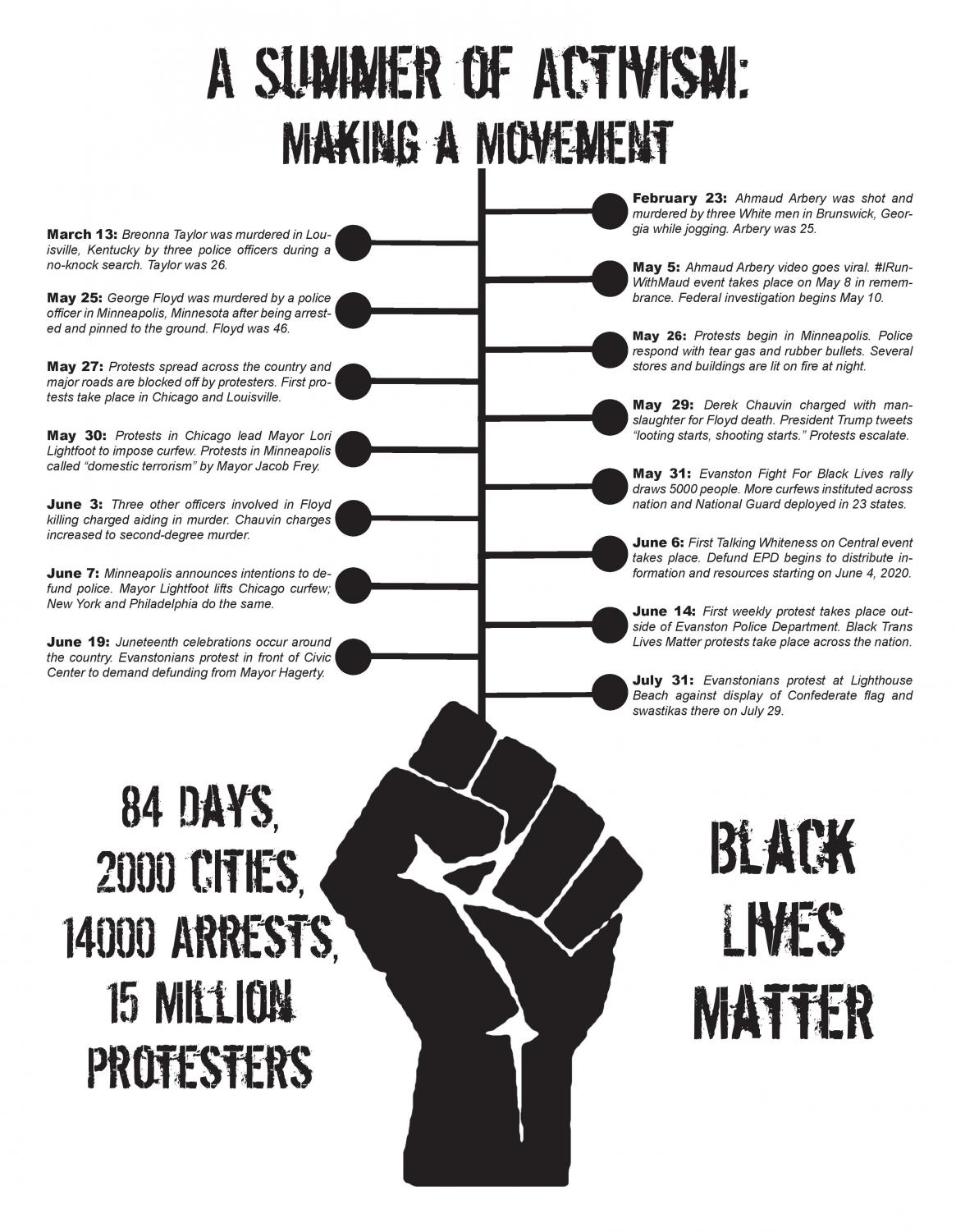

February 23. Ahmaud Arbery was murdered in Brunswick, Georgia.

March 13. Breonna Taylor was murdered in Louisville, Kentucky.

May 25. George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

These three murders sparked a movement. These three murders sparked a revolution.

In the weeks and months following these deaths, and the deaths of countless other Black men and women throughout our country and across our history, many found themselves at a tipping point. The continued cycle of violence against the Black community and the continuation of centuries old oppression by systems of power needed to be rethought, reformed or destroyed. Protests erupted across the country as people of all races and creeds cried out for justice. These cries spread like wildfire from the streets of Minneapolis to the beaches of Los Angeles and the parks of New York. They echoed across the world and were met with responses in Sydney, London, Tokyo, Lagos and Nairobi, and reverberated back to Chicago and Evanston.

At the heart of this movement is a truth: Black Lives Matter.

A simple, apolitical fact.

The youth leading the movement have many goals—to reform and defund police departments and justice systems, to examine the role of systemic racism and whiteness in our societies, to bring resources to communities who have been ignored and imprisoned for generations—but at the core is the underlying belief in the humanity of others.

Black Lives Matter.

The Protests

The Evanston community has hosted a wide range of protests and events aimed towards addressing, preventing and eliminating racism over the past several months in light of a new wave of activism nationwide. Groups including Evanston Fight For Black Lives, Defund EPD, E-Town Sunrise and Talking Whiteness on Central have taken steps on a communal level to propel the Black Lives Matter movement forward and ultimately work towards racial justice.

“I think Evanston is trying to do more than many cities. That’s what I love about Evanston, so many residents are engaged and now so many young people . . . are really getting engaged in city issues, and we’ll see over time the changes that come about as a result of that,” Evanston Mayor Stephen Hagerty expresses.

The first major event in Evanston took place on May 31, more than 5,000 people marched and rallied at the peaceful protest planned by Evanston Fight for Black Lives to call out systemic racism within the police force and the racial inequality that has been normalized in American culture.

“We try to speak at the City Council meetings on Monday. On Sundays, we’ll paint [Defund Evanston Police Department (EPD)] in front of the police department and try to get folks in the community to kind of better grasp and understand what we mean when we say that. We just did a yard sale where we had different clothes and stuff like that. Then, we donated it to Assata’s Daughters and other organizations,” says Evanston Fight For Black Lives founding member and 2019 ETHS graduate Liana Wallace.

Wallace emphasizes that Evanston Fight For Black Lives is a persistent force by taking action through a variety of different protest methods. Consequently, the protests have had a significant emotional impact on many Evanston community members.

“The protests made me happy, made me proud, made me realize that maybe people of color were coming to a different place of being humanized by people who don’t look like I do,” shares Marcus Campbell, ETHS Assistant Superintendent and Principal.

Although identifying and exposing institutionalized racism is important, that is not the extent of the organization’s aims. Evanston Fight for Black Lives, founded by eight Evanston alumni, has one particular call to action: to defund the EPD.

“[Defunding the police] means taking funds away from the police department, or what we have deemed to be policing for right now, and using those funds to either create or put money into other programs that actually reduce crime,” explains a founder of the organization, Nia Williams.

While some Evanstonians support the Defund EPD movement, others have voiced their concerns regarding the possible defunding of the EPD; they feel as though their safety could be compromised with this proposal.

“Everything deserves critique, but most of the time when people are critiquing defunding the police, they’re coming from a space of privilege,” Williams says. “Therefore, the next question I ask them is, ‘How many times do you interact with the police?’ or ‘Are those interactions good or are they bad? What are we defining as good and bad? Why can’t we stop crime before it happens? Why are you so against putting money into the community, and so for putting money into locking people up in cages?’, because that is essentially what police do.”

Evanston Fight for Black Lives is not alone in their mission to defund the police. This summer, the 2021 City Budget will be modified and confirmed by the Evanston City Council. Therefore, Defund EPD formed as a group dedicated solely to pressuring the government to deduct financing towards the EPD, and in turn, invest money in other aspects of the community.

“For too long, policing and enforcement have been favored in place of actual support in our community. Traditional reform has failed. Specifically, it has failed Black folks—in Evanston, in this country, and around the world,” reads the Defund EPD official Instagram page. “The time is now to embrace transformative justice and non-reformist reforms.”

Defund EPD leads the “Every Sunday Protest” outside of the EPD, which creates weekly racially driven conversations regarding defunding the police.

“In the past few months, I have actively used my body in protests and addressed the systems of oppression within my community such as the EPD,” mentions ETHS senior, Izzy Basso. “I have followed existing organizations within the community to stay updated on events and ways to get involved.”

For some, reallocating funds is just the beginning of an overall plan of complete elimination.

“I think also, [defunding the police] is a step towards abolition, because we don’t actually need what we call ‘policing’ right now,” Williams reveals.

Intersectionality is also central in this movement, seen in climate action group E-Town Sunrise endorsing the Black Lives Matter movement and the push to defund the EPD. They have used their platform as an existing activist group and collaborated with local organizations, such as Evanston Fight for Black Lives, to drive the movement further.

“Sunrise put out a statement in solidarity with Black Lives Matter, and we’ve just been focusing on that ever since,” says E-Town Sunrise member and 2020 ETHS graduate Aldric Martinez-Olson. “Since we are primarily a political organization, we’ve been pushing for Black progressive leaders to get elected who support police defunding, along with progressive climate policy.”

A separate activist group in Evanston has taken a different approach to addressing racism in the community. Founded by three Evanston graduates, Talking Whiteness on Central highlights North Evanston and works to include that community in conversations surrounding race and equity, given its majority white population.

“A lot of the time it’s easy for white folks to ignore things going on,” Talking Whiteness on Central member Caroline Jacobs admits. “The idea that we’ve embodied as a group is to change that and bring these conversations and put them on white folks, because this shouldn’t be on the back of people of color and Black individuals.”

Talking Whiteness on Central has planned and executed numerous events that work to educate North Evanston residents about existing racism within the community and normalize conversations that highlight white privilege in white households.

“We’ve had some people saying that we should be including more people of color and saying that white people talking about race is inappropriate, and I think there’s sort of a miscommunication there that we aren’t talking about race but about whiteness specifically,” Jacobs enunciates.

Whether it’s 5000-person protests or constructive conversations, racial activism in Evanston has reached its highest peak since the Civil Rights Movement in the mid-20th century with numerous activist groups in the community working towards a common goal of defunding the EPD and eliminating systemic racism. Public response has varied, but these groups have undoubtedly made their mark.

Jacobs concludes, “One of the amazing things about living in Evanston is that we can be proud of where we live. I love Evanston so much . . . and because I love Evanston, we want to find ways to make it better. You can still have that Evanston pride and try to find ways to address the injustices and the racism that exists here.”

Public Reception

At the forefront of Evanston’s activism is young people. They are the leaders of many of the city’s most impactful organizations. Evanston Fight For Black Lives, Defund EPD, Talking Whiteness on Central and Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR) are all run by Evanston’s youth.

“I think in terms of what’s going on in Evanston, I think Evanston is actually doing a really great job, especially the youth,” says Howard Godfrey, an ETHS senior.

Evanston’s Black Lives Matter activism has been orchestrated by primarily young people, and this has been acknowledged by the city’s government.

“This is very much a generational kind of issue, more than racial. If I’m 50 and I have other friends in the community who are Black, who are similar in age, all of our children all feel very strongly that policing is absolutely broken, we need to defund the police,” says Mayor Stephen Hagerty.

SOAR Board Member and ETHS senior Meena Sharma discusses what it means for white Evanston residents to acknowledge their privilege and understand the areas in which the community needs to change.

“The first thing that comes to mind when I hear equity and race in Evanston… is concealed because Evanston claims to be this place where great conversations take place and there’s a lot of progressive action, but it’s really limited to the conversations people are willing to have,” Sharma adds.

“If you heard of the instance at Lighthouse Beach, where these people came and hung a Confederate flag and it wasn’t until a Black woman showed up that the situation was addressed. So even though there are certain people in Evanston, specifically white folks, who want to have conversations about equity and race, [they don’t] dive deep enough to the extent where people can actually show up.”

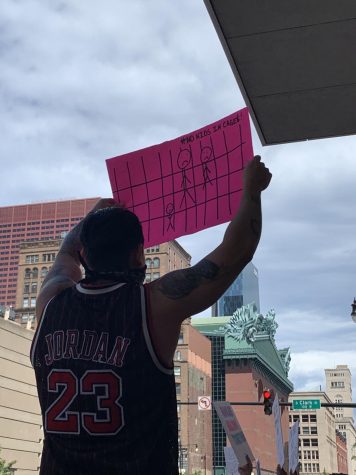

While Evanston frames itself as a progressive, primarily liberal city, there have been controversial events occurring over the past few weeks. One such event took place on July 29 at Evanston’s Lighthouse Beach when Black resident La Shandra Smith-Rayfield confronted a group of beachgoers who had hung a Confederate flag towel on the beach’s fence. According to Smith-Rayfield, at a protest held two days following the event, the group hanging the Confederate symbol was not shut-down until she stood up.

Tackling such a complex topic as systemic racism in Evanston means that action has to be taken by people of all races. According to Sharma and Liana Wallace, that is something many of Evanston’s more privileged residents still need to do.

“I think a lot of white families have and families with a lot of resources have to realize that they have to give up things in order for equity to actually take place, which I don’t think a lot of people in Evanston understand,” says Wallace. “[For example] people get very threatened when you’re talking about schooling, because a lot of people move their kids to Evanston for equity and diversity, but they don’t understand what should come along with that, which can be very challenging and frustrating.”

Beyond the events of Lighthouse Beach, a similar hateful action took place on July 3 following the painting of a Black Lives Matter mural on Dodge Street in front of ETHS by the Boy’s Basketball team. However, just hours after the mural was completed white paint was thrown over the yellow letters spelling ‘Black’.

“There’s a part of me that believes these aren’t Evanstonians doing this [i.e. bringing a Confederate flag to Lighthouse Beach and defacing the Black Lives Matter art in front of ETHS], but even so, my views of Evanston haven’t changed,” Marcus Campbell says. “I still believe that of all the places to really work at racial justice, Evanston is positioned more than any other city in the country. Evanston still has to reconcile its histories and what it still does, but I have faith in Evanston, I believe in Evanston and my views of Evanston have not changed.”

Reflecting back upon Evanston’s past has been another discussion. Topics such as gentrification, education and redlining are all a part of Evanston’s history, and, moving forward, young people feel that addressing Evanston’s past racism is essential for creating a more equitable community.

“As diverse as we are and as liberal as we are, we see a giant achievement gap within our education system, we see social segregation at our lunch tables, we see North Evanston which is 97-98% white…. If you look at the history of Evanston, it’s kind of messy, and I think there’s something to looking at that messiness and figuring out what we as white people can do and that’s part of this project…. It’s complicated and the first step is recognizing Evanston’s history and Evanston now and seeing what’s there to be done,” says Caroline Jacobs.

The impact of Evanston’s history of racism is shown through its demographics. According to 2010 U.S Census data, there was a decrease of over four percent within the Black population in Evanston from 2000 to 2010. This decrease can be attributed to significant property and income tax increases the state has made since the 2007 recession which has made it difficult for many families to continue living in Illinois. The state’s property taxes specifically affect Evanston residents, but primarily hurt its Black communities. While more affordable housing is being built, it is not enough for many residents to continue living in the city.

“In Evanston, people really love to talk about equity and Evanston’s diversity, and it is interesting because a friend of mine pointed out to me if you walk through Evanston, you see tons of Black Lives Matter signs, but we don’t pay attention to the diminishing population of Black folks within Evanston because property taxes are rising. There’s no affordable housing or things of that nature,” says Wallace. “We in Evanston say that we value Black lives, but in reality, a lot of the things that we say that are working towards equity, are actually not good enough and are not benefiting the Black community.”

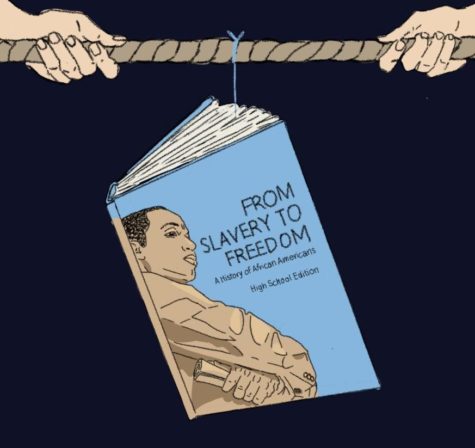

If recognizing Evanston’s history will lead to systemic change, many believe that addressing Evanston’s areas of inequities in school is important to bringing that change about.

Aldric Martinez-Olson reflects upon his experience at ETHS, “I have walked out of those four years with a better understanding of race and how it affects me, how it affects my peers and how it affects the systems in this country.” Martinez adds, “I have the concern we don’t really learn about segregation in Evanston, which was very common despite how progressive we are. Redlining was a huge issue, and it has added to a lot of the inequity that we see today. We could be a very different community, more integrated and more uplifted if we didn’t have these implicitly racist policies shaping the way people could get housing, education and other resources.”

While discussions around racism in Evanston can be overlooked, SOAR’s mission is to provide spaces at ETHS that focus on discussing racism within the high school and the broader community.

“I was really involved in SOAR, and what I always come back to is that SOAR taught me agency. It taught me self-love as a Black woman and what that looks like to demand that as you walk through the world.” Wallace adds about her experience at ETHS, “But I think something that I really learned was that I kept unknowingly pushing the conversation towards. Let’s get white folks to understand this work. Let’s make sure they’re not microaggressing people and let’s make sure they know not to say the n-word. In reality, I wasn’t even centering the Black voices within ETHS.”

As SOAR is working to expand discussions about Evanston’s history of racism, work still needs to be done to bring them to every classroom.

“Even if you’re in a math class, let’s say if you’re in AP or an honors Math class, and if it’s what I’m assuming [is] predominantly white, that right there is a product of Evanston is history: of bussing and discrimination and unfair access to tutoring and resources for Black and brown students. I think that conversation can be found in every single classroom,” says Sharma.

Confronting and correcting one’s own racist actions has been many people’s core lesson from this movement so far. Yet another is listening and understanding; this can be seen by social media posts with the statement “I understand that I will never understand, so I stand.”

“I think that the foundation of this entire movement is, ‘Please listen.’ It’s because no one is resorting to insane methods for no reason. We just want to be heard. So, if anything, at the end of the day, we just have to learn to listen and to educate ourselves and to learn from one another,” says Godfrey.

Wallace expands on the concept of listening and learning by saying the conversation around race should be centered around the voices and perspectives of people of color.

“It takes [other] people to hold you accountable to see your blind spots because racism is complex; it’s a beast. So you might be thinking you’re doing stuff to really benefit the community and in actuality, I was not centering Black voices enough, so instead of centering it on white people… you have to center it on Black people.” Wallace adds, “They are kind of like the bread and butter of re-imagining what liberation could look like. So time is better spent when you build up the Black community and give folks resources and just center their voices above everything else.”

Government Response

Though national and regional authorities in certain parts of the country are meeting protesters with aggressive tactics, many of Evanston’s current leaders are in support of youth activists who are hopeful to make great change. However, there are many others who remain skeptical of the current movement.

“I’m really impressed by the young graduates [and current students] who have gone to college and have gone back to continue their work. They’ve all been really active in past years and are standing up for human rights. I’m moved and excited by their efforts and their efficiency to provide a new stream of consciousness,” says 2nd Ward Alderman Peter Braithwaite.

However, while there are those within the city government that support the goals of the Evanston For Black Lives movement, the process towards change within bureaucracy is slow. No matter the speed, it is happening.

“I’m going into my fourth year [as mayor] right now, so I’ve been through three budget cycles and not once in any of these cycles have people come forward and said we need to look at this police budget,” Mayor Stephen Hagerty says. “As elected officials, we’re always looking at the budgets, but in terms of the examination and reimagining that’s going on right now because of this movement of defunding the police, that has not happened and I think that’s a good thing.”

Defunding the police has become a national movement that calls for the reallocation of police department funds into other areas of support for communities. Meaning if the job of the police is to control crime, doesn’t it also make sense to invest money in resources that aim to prevent crime from ever happening? These redirected police funds would go to better support underprivileged communities through increased spending in education, community services and development, social services, violence-prevention work, housing and other programs that have historically been underfunded.

According to Hagerty, the police budget will likely shrink in the coming months, however, that change is due to the ramifications of COVID-19.

“I do think there will be changes to the police department. The question is will it be defunded in the way that the movement is asking… the reality is that we have a 12 million dollar deficit [because of COVID-19]… so we’re going to defund everything, but that’s disingenuous… since that’s not what defunding the police means since it means reinvestment or reallocation into other areas,” Hagerty says.

Protests, in particular, have played a significant role in advancing conversations surrounding the actions and intentions of police officers at the city level. While EPD aims to prioritize what’s best for the community, de-escalate situations and broaden the outreach for conversation, re-envisioning the role of officers in Evanston and investing in less intrusive means of community support is what needs to happen.

“Our goal in what we’re trying to do is figure out, as a community, [is] what Evanston looks like without police officers . . . Our goal is to provide people with basic necessities so that we can move towards defunding and, eventually, abolishment,” Nia Williams says.

Williams also explains how Evanston’s institutions, which include housing and criminal justice, oppress marginalized groups, because of the way our system operates.

“We have to understand how other systems that are not policing are systemically racist. We can put money into housing people, but we also need to talk about how housing has disproportionately discriminated against Black and brown folks. We can put money in there, but we also need to address the racism in those systems. I think defunding the police encompasses all of that, and how we are going to destroy and then rebuild a system that finally works for all people,” she adds.

In response to Defund EPD, members of the City Council have come forward with their thoughts regarding the possible dismantling of the Evanston Police Department; including Hagerty, Braithwaite and 9th Ward Alderwoman Cicely Fleming.

“I’ve sort of been painted out there as Hagerty’s opposed to defunding the police and what I said was to [activists] that I can’t sign on to that commitment that they want me to sign on to… I’m completely open to setting the table in the community as the Mayor that we will have a complete and thorough examination of the budgets and the operations of the police,” Hagerty says.

Braithwaite argues understanding the goal of defunding is comprehensive in working towards the next step.

“Once you get past the word, and you get to the substance of the work, that’s the challenge. You have to go beyond the polarization of the word [defunding] and once you get to the substance, the conversation becomes easier.”

Similarly, Fleming makes her stance clear on Defund EPD.

A blog post from June 19 reads, “Defunding is a reasonable and achievable government action. I stand ready to support defunding EPD. I am ready to fill our community with more services while working towards making Evanston a place where we don’t equate safety with guns and arrests, a city that actually practices radical racial justice.”

Earlier in 2020, Evanston made history by becoming one of the first cities in the country to institute a 10 million dollar reparations fund aimed at preserving and enhancing the Black community of the city. The fund is a step toward racial equity in Evanston and focuses on correcting Evanston’s past inequities such as redlining and the racial wealth gap. Reparations will go towards providing housing and financial resources to Black Evanston residents.

While dismantling structural racism within policing, housing, education and other institutions is a goal across the board, racial equity will not be achieved through reparations or through defunding the police alone.

“We’re constantly evolving towards justice…. You don’t really set out this work to do it perfectly. You just want to start it and realize that the journey is imperfect, we’ve all been socialized in these white normative behaviors, our policies have done it, and it’s happened for generations and generations. Coming to a new understanding, beginning to undo some of what’s been done and holding space for where there’s a contradiction and where there’s tension is really important for us,” Marcus Campbell says.

Additionally, Campbell notes how the young activists of Evanston continuously break the mold and push the boundaries of conversation.

“I have been overwhelmingly warmed by the conversation and the willingness that Evanston has shown in having very difficult conversations. That gives me a lot of hope. Youth are pushing these conversations and have always done that,” he concludes.

Regardless of the pace of government action within Evanston, one thing is certain; this movement shows no signs of slowing down.