Different demographics breed different forms of activism

March 23, 2019

ETHS English teacher Anita Bucio, who identifies as Indian American, graduated from New Trier High School in 1998 where she experienced racial prejudices. Bucio has not been back to New Trier since her graduation, even though she lives in a neighboring community.

“I think the difference between [New Trier] and [ETHS] is when you come from uber-wealth and privilege, which most of the students at New Trier do and many of the students at Evanston do, you live in a bubble where you have certain perceptions, beliefs and experiences that shape your reality, so you are unable to understand what it’s like to feel like your not welcome,” Bucio says. “And at Evanston, you see two worlds, you see a world that’s like the New Trier community, the upper, super-affluent side and you see the side that is not. I think that trickles into the school and I think people believe that since this is a diverse place, those problems aren’t there, but those problems still exist.”

When attending New Trier in the 1990s, Bucio encountered racism from her fellow students and teachers. She explains that there was a divide at the school.

“You saw it when you entered New Trier. You saw people of color sitting together and you saw the super athletic kids together, I mean it was really clique-ed up,” Bucio adds.“You could see students of color sticking together, and they would be together because they were all experiencing the same thing.”

Similar phenomena still occur in New Trier and ETHS today.

“Everyone stays with the people that they’re like,” New Trier student Sophia Kurzman, who identifies as white, says. “But everyone’s really accepting of other races. Black people are rare, but they’re accepted and everyone treats them normally.”

New Trier Assistant Superintendent for Student Services Timothy Hayes further explains the racial dynamics of New Trier’s student body.

“When we talk about the impact of race on students of color at New Trier, we’re talking about a group of students who are experiencing going to a school in which they are very much the minority,” Hayes says. “There may be only several dozens of people in the school who share your racial identity. For students of color in our school, that experience can be very lonely.”

ETHS is statistically more diverse than New Trier, with 45.4 percent of white students compared to New Trier’s 82.5 percent. But numerous accounts of racial prejudice and self-imposed segregation reveal that Evanston’s greater diversity does not necessarily equate to a community free of racism.

“The student body is generally accepting of people’s different identities, however, there is miscommunication about ways to support other students and they identify without dominating over voice or space.” ETHS senior Erin Ikeuchi says. “We’re having a lot of conversations about it, especially at the race summits.”

ETHS addresses matters of equity in a variety of ways — through summits for different affinity groups, education initiatives geared towards closing the achievement gap, all-school presentations like Calvin Terrell’s “Healing Historical Trauma” exhibit, and student-run equity-based clubs such as Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR).

“[SOAR’s] mission is to create an anti-racist environment whether that be in the school, the community, and hopefully the world,” senior and SOAR member, Nia Williams says.

New Trier also has groups and clubs centered around student identity, like the African American club and Black Student Union, which are meant to provide a safe space for African American/Black students. A student-run club similar to SOAR called Voices and Equity meets with staff members to discuss and address equity issues within the school and community. But historically, New Trier has struggled with talking about race, perhaps because of their racial demographics.

“85 percent of our student body is white, and speaking as a white person, the challenge with being white and having a conversation on race is that we’re taught as white people that we’re not supposed to talk about race, and that we don’t really have a race,” Hayes says. “For the majority of our students, they may not have really ever engaged in a conversation about what it means to be white in America. So they can go for most of their education and not have that discussion.”

Hayes acknowledges that this is problematic and recounts an example of when the idea of talking about race brought up feelings of discomfort among New Trier parents.

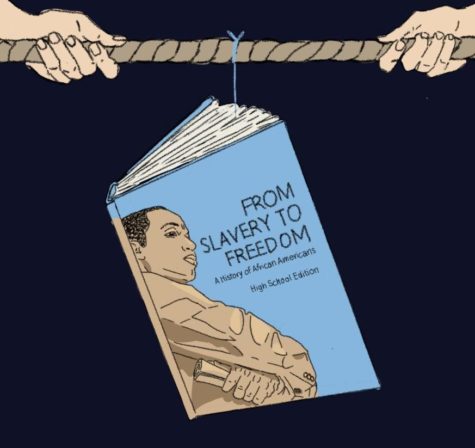

In 2016, New Trier altered their school schedule for construction purposes, adding Martin Luther King day as a school day. The school board decided to have a Seminar Day on MLK day about Dr. King’s legacy and its impact on modern America. The following year in 2017, New Trier held another Seminar Day titled “Understanding Today’s Struggle for Racial Civil Rights”, which sparked controversy from a group of New Trier parents.

“There was a small group of parents who became concerned about the day, and began a petition drive to petition the board to either change the day — they wanted to add own speakers — or they wanted the board to cancel the day,” Hayes says.

Hayes says that some parents felt as if the day was politically biased, and worried about what it would mean to talk about race, offering that the day was about “trying to make white kids feel guilty.”

Both ETHS and New Trier have also used protest as a means to counter issues, such as the issue of gun violence. Following the Parkland shooting, last February students from both schools participated in the National Walkout against gun violence.

New Trier student Alex Gjaja reports that the Walkout at New Trier led to larger conversations regarding the safety of the students, especially after construction work included an installment of new windows, causing some students to feel unsafe.

ETHS students approached the issue from a different lens. Rather than working with the administration to improve safety measures within the school, students poured their energy into protesting guns and gun violence itself. However, Williams felt as though the walkout was geared towards white victims of gun violence.

“I did not attend the walkout. It felt to me that my black body was not going to be included in this struggle against gun violence,” Williams says. “I only say this because I had never seen ETHS students walkout when black bodies have been killed every day and I found it extremely uncomfortable and upsetting that bodies only mattered when they did not look like me.”

Economic status is another topic that both ETHS and New Trier struggle with discussing.

The average household income within New Trier District 203 is $262,814 while within Evanston Township High School District 202, the average household income is $115,582. Data from Illinois Report Card states that 38.4 percent of Evanston students are considered low-income and 3.7 percent of New Trier students are.

“It’s easy to forget when you live in this community that there are people with financial concerns,” Gjaja says.

Joshua Brown, an ETHS English teacher, went to New Trier in the 1990s. He discusses a time during his freshman year when his father lost his job.

“Several of my fellow students said something to the effect of ‘well, anybody who wants a job can get one, it’s just a matter of people being lazy or not’,” Brown says. “I think I didn’t share that my father was unemployed, but I always remember being embarrassed about that and feeling like there wasn’t really a place for that to be said.”

Although statistically, New Trier lacks racial and economic diversity, the school emphasizes and encourages diversity among political ideologies of students — more so than ETHS, where the student population is overwhelmingly left-leaning.

“Sometimes at Evanston, I can find a middle ground with people, but I feel like there are some people where once I just say ‘yeah, I’d say I’m a conservative’, it just stops, the conversation ends, they walk their own way,” ETHS sophomore Chris Giella says, who identifies as conservative Republican.

Many clubs at ETHS encourage political activism from students. But most of these clubs, including the official student government club, Student Union, encourage activism that reflects the typical values of the Democratic party.

“I feel like a lot of things at ETHS are very left-leaning, so maybe [ETHS] getting more involved with some conservative things too could be a way to raise more awareness of other political opinions,” Giella says.

Opposingly, New Trier has clubs for multiple political identities including the Trevian Republicans club and the Young Democrats club. Students are open about holding a wider range of political views — whether attending meetings for their party’s clubs or dressing in attire representing their party.

“People wear MAGA hats and people wear Hillary shirts and it’s not something that’s hidden. It’s not something people will get upset about,” New Trier junior Stella Kustra says.

“Even if NT students might not be actively going to marches, or actively campaigning for candidates or doing some of that active social justice work, they are always willing to listen, which is something I appreciate,” Gjaja adds.

Contributor: Zosia Johnson