Peeling away the layers behind Pathways to Honors

December 13, 2019

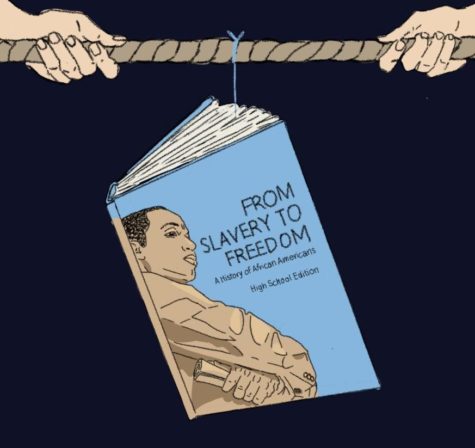

In 2010, ETHS gave its freshman curriculum a massive facelift. This complete detracking of the Freshman Humanities and eventually later courses sought to remove historic impediments to provide greater access and opportunities for underrepresented student groups with the hopes of creating a more equitable classroom experience for its students. Now, nearly a decade since its implementation, Pathway to Honors, formerly known as Earned Honors, has not only increased the number of students of color in AP classes, but also increased the number of college-ready scores of three on AP exams. While Pathway to Honors has boasted upward trends in achievement and positive qualitative student experiences, many would agree that there is still more work to be done.

The Pathway to Honors system was implemented as a way to challenge and restructure a once-flawed system of tracking that perpetuated the opportunity gap and subsequent achievement gap between white students and students of color.

“We had five tracks initially that students entered in freshman year based on their eighth-grade test scores,” Associate Superintendent for Curriculum and Instruction Peter Bavis says. “What we found when we looked at the data was that once students were tracked into a level, they stayed at that level.”

Bavis introduces a common phenomenon that often occurs during tracking, or “ the practice of grouping children together according to their talents in the classroom,” according to the National Education Association. Bavis furthers this explanation in regards to high-tracked students.

Humanities placement, in specific, was based on the EXPLORE Reading test, which is the ACT’s college readiness test for 8th and 9th graders. Students with EXPLORE Reading scores between 40 and 69 percentile were placed in mixed-level regular classes; students with EXPLORE Reading scores between 70 and 94 percentile were placed in mixed-level honors classes; students with EXPLORE Reading scores at the 95th percentile or above were placed in honors-only or high honors classes.

“If you were tracked into what was called high honors at the time, which was students in the 95th percentile and above on some rate on a reading test, we found that those students traveled together freshman, sophomore, junior, senior year,” Bavis says. “Those were the students who had access to the Advanced Placement courses, and the rest of the students, for the most part, did not. Where you were placed in eighth and ninth grade before you ever set foot in the high school determined your academic outcomes as a senior.”

With the creation of Pathway to Honors, these barriers, often established long before students reached high school, have been mitigated, allowing students to receive honors and eventually the possibility of taking AP courses, not on the basis of one singular test, but on the basis of their learning and comprehension in the classroom.

“There were two schools essentially in one building—one for students who were on the honors track, and one for students who were not,” History & Social Sciences Dept. Chair Nicole Parker says. “And so, in eliminating that, and giving all kids the opportunity to earn honors, we’ve changed not only the social dynamics of the school but also opened up the door of opportunity for students to earn honors credit, and then also on that pathway perhaps take more AP courses and then finally to be able to be more college and career ready.”

However, another issue with ETHS’ previous system of tracking, as Bavis indicates, was that it enforced the concept of stereotype threat, where students feel at risk of conforming to usually negative stereotypes about their social or racial group.

“When an institution labels or society labels somebody, there’s a whole lot of power that comes with that,” English Teacher Julie Mallory says. “When you take that away, that lets people be who they are without some sort of stigma attached.”

A possible explanation to this, as Bavis suggests, could result from the inconsistent expectations set in each class at the time. Oftentimes, teachers built curricula based on their subjective perception of what their students were capable of. In creating the Pathway to Honors, administrators were intentional in crafting clear expectations and guidelines of how students could earn honors credit. The previous tracking system, on the other hand, allowed for inconsistent expectations, creating clear inequities in the skills and practices fostered in the respective classrooms.

“There was a time in this high school where if you were in a two-level or a regular level class, you didn’t get the best curriculum. You got whatever the teacher thought that you should have, and that was in large part based on race because the kids in the middle and at the bottom were the black and brown kids,” Assistant Superintendent Marcus Campbell says. “If I don’t have high expectations of you, then I’m not going to give you the best, I’m going to give you something that I think you can do.”

However, the work is far from done, with some administrators, teachers, parents and students referring to the Pathway to Honors process as merely “a step in the right direction.”

“There’s many layers to closing the achievement gap, and I think that the Earned honors is one step toward equity. But as far as closing the achievement gap, I would not say that ETHS can wholly be responsible for that,” ETHS School-Wide Reading Specialist Kiwana Brown says. “There’s things that need to start way before kids get here. But I do think that [Pathway to Honors] is one step in the right direction.”

Rollout of Pathway to Honors courses

Freshman Humanities

ETHS began the Pathway to Honors implementation with Freshman Humanities classes for the 2010 to 2011 school year following the school board’s approval in December 2010.

According to the first Restructured Freshman Initiative Evaluation Report, students must have a C or higher in the class, and at least an 80% average on honors assessments in order to earn honors credit. Mallory worked with administrators and other Humanities teachers to detrack the freshman curriculum in early 2011 and recalls some of the initial challenges introducing the curriculum and assessments.

“[Pathway to Honors Assessments] used to be like this big ‘Ta-da! Now we’re going to earn our Honors credit’ and there was a big event that happened that was really stressful,” Mallory says. “Over time become more comfortable with, ‘You know what? We can just blend that honors credit assessment into the curriculum into the way that this course is structured.’”

Brown taught English classes before detracked Humanities and recalled engaging students in a range of novels and types of writing while the current Pathway to Honors model is “more about quality instead of quantity.”

Parker underscores the quality of skill development in classes like Freshmen Humanities.

“It now has become the practice for us to talk explicitly about honors credit skills with students, and so even if you haven’t mastered the skill yet, keyword yet, at least you’re now exposed to it,” Parker said. “We talk about things explicitly, like use of evidence, reasoning, claim. Those are things that did not happen across the board for all students before this program.”

Biology

The year after Freshman Humanities became Pathway to Honors, Biology was redesigned. Biology teacher Adriane Slaton notes that changes have allowed for “the teacher to create a lot more spaces and curriculum that they are passionate about, that they can get students passionate about.”

The initial Biology Pathway to Honors assessments were based on college readiness standards that focus on skills like graphical analysis, reading graphs and making arguments from data, according to Slaton; these skills are assessed on the ACT Science section. While assessments were designed this way, Slaton clarifies that Biology is now “in a great place in curriculum development to analyze whether the earned honors assessments should play such a large role in determining if a student earned honors credit.”

Teachers like Slaton recognize how students taking Pathway to Honors Biology may take AP Biology, another course she teaches, or other AP science courses, but these courses are not the end goal of Pathway to Honors Biology.

“Our hope is that Earned Honors Biology is rigorous enough to build foundational skills and confidence so students can take AP or any of the other amazing science classes ETHS offers in the future.”

Civics, Sophomore Writing & Junior English

Civics and Sophomore Writing were implemented as Pathway to Honors courses in 2017.

The design of Civics was also informed by changes to Illinois education mandates for students to receive a civics education, according to Parker.

“For sophomore year, we have really discreet statements about skills. And we’re building on what happened with freshman year,” Parker said. “And second semester, in particular, [we’re] looking at oral communication.”

Like Freshmen Humanities, the Sophomore Writing curriculum focuses on reading and writing skills that students compile in their Pathway to Honors portfolio. The Junior English course is in its first year of implementation. Mallory, who has taught Sophomore Writing and currently teaches Junior English, indicates that the skills and assessments of these classes are aligned to the Pathway to Honors framework towards equitable opportunities for students.

“I think that there’s a population of students that wouldn’t have had an opportunity to earn honors credit,” Mallory said. “[Those students] realize that, ‘Oh, there’s no mystique to this. I just have to do the work and apply the feedback and maybe I do a revision or something, but, I’m capable,’, and I think that goes a long way.”

Geometry

After three years of planning, Geometry is in its second year of Pathway to Honors implementation. Geometry was particularly difficult to transition as there were many different standards.

“If we’re going to have the best geometry class, what are the standards we have to cover?” says Math Dept. Chair Leibforth. “And then we want to take those and go at a deep level with them.”

The Pathway to Honors course was structured around 28 Common Core Standards isolated as essential for students, according to Leibforth.

During its first year, the Pathway to Honors assessments focused on seven learning targets per quarter (or LTAs) that students retook until they mastered them. There were also free response questions with reflection modeled after AP style questions and a semester-long comprehensive problem with reflection. According to Liebforth, the following semester teachers made adjustments to assess honors-level problems for students to master earning honors credit on unit assessments.

Math teacher Dawn Eddy thinks the changes to the assessments better demonstrate that students can do honors level work.

“Our second semester really represents what it is now,” Eddy says. “There were four earned honors assessments as a part of each unit test within the semester. If students averaged 80% or better on those assessments, they earned honor credit.”

Complexities of “Achievement” Data

Pathway to Honors courses aim to provide equitable access to Honors and AP Level courses, particularly for underrepresented student groups often denied such opportunities under the previous tracking system.

To better assess student success, ETHS generates an annual Student Achievement Report, detailing data in areas such as standardized test scores, GPA, AP enrollment and scoring and overall college readiness. This report, which is annually presented to the school board, provides quantitative information about the achievement of different groups within the school.

ETHS administrators have presented data to show that the introduction of Pathway to Honors courses has increased student achievement, evident in the increased percentage of each cohort receiving honors credit, larger enrollment in AP courses and an increased percentage of students in AP courses earning a three or higher on AP exams.

“Students who would have been tracked into a regular level are performing at higher levels than they would have before,” Director of Research, Evaluation and Assessment Carrie Levy says.

After examining the Student Achievement Reports for the past ten years, which are available on the ETHS website, The Evanstonian notes that some of these trends are difficult to confirm from our own reading of the data. There have been inconsistent metrics in the language and indicators of academic success due to changes in state and district’s data evaluation practices.

Prior to the 2016-2017 school year, data around GPA was released as a series of averages, with those values being calculated for various student populations grouped by race, grade and gender. However, since 2016, the data around GPA was presented as a percentage of students with a 2.8 unweighted GPA or higher as mandated by the Illinois Every Student Succeeds Act (IL ESSA). 65% of students in the class of 2017 graduated with an unweighted GPA of 2.8 or higher, 63% of the class of 2018 and 65% of the class of 2019. Because of this change in how GPA data has been tracked, The Evanstonian could not determine a clear trend in GPA growth due to Pathway to Honors.

The percentages of students taking AP exams and scoring a three or higher on those exams are noteworthy. The percentage of students taking at least one AP exam has steadily increased since 2006 with the highest percentage of students taking an AP exam in 2018. In Bavis’s article “Detracked — And Going Strong,” published in 2016 in Phi Delta Kappan, he states that the first group of students to have taken Freshmen Humanities graduated in 2016 with the highest average ACT score of a 23.9 in school history and the highest number of college-ready scores of 3 or more on AP exams. Pathway to Honors doesn’t just aim to promote accessibility of these classes; it also works to promote student success in these classes.

“There are huge increases in the numbers of students of color in both honors and AP classes, without a diminishment of success in students of all colors scoring a three or above,” School Board Member Gretchen Livingston says. “We have been able to maintain a high and increased number of students scoring three and above.”

According to Bavis, scoring a three and above on an AP exam is considered “college ready.” Illinois public colleges and universities legally mandated to grant college credit for scores of a three and above. Since 2005, the percentage of ETHS students scoring a three and above on at least one AP exam has fluctuated by cohort with an average of around 72%. In 2016, 71% of students scored a three or above on at least one AP exam. In 2017, 73% did and in 2018, 64% did.

Beyond AP exams, it is challenging to understand the data around achievement on other standardized tests based on achievement reports currently available to the public. Prior to the 2016-2017 school year, Illinois changed its state-mandated standardized test score from the ACT to the SAT. While these tests don’t differ drastically, it is difficult to establish trends in student achievement based on test scores since the tests changed. Additionally, the 2015-2016 Achievement Report shows 2015 marked the last year that eighth grade students in District 65 took the EXPLORE reading test, which had been used to place students in different level classes for Freshmen Humanities and Biology freshman year. That test was also used to measure growth over a student’s time at ETHS, comparing EXPLORE scores to ACT scores.

The reports also reflect the changes in how achievement is measured. The 2015-2016 report is the first one to use a college readiness metric, defined by the Illinois Every Student Succeeds Act (IL ESSA).

According to the IL ESSA, established in 2015, a student is deemed college ready if they have an unweighted GPA of 2.8 or greater, 95% attendance and proficiency in both English/Language Arts (ELA) and Mathematics. A student is proficient in ELA if they earn an A, B or C in an AP English class, score a three or higher on an English AP exam or earn an SAT subscore in ELA of 480 or higher. One is deemed proficient in mathematics if they earn an A, B or C in Algebra 2, score a three or higher on a math AP exam or earn an SAT subscore in mathematics of 530 or higher.

65% of students in the class of 2019 met one or more of the ELA benchmarks and 78% met one or more of the mathematics benchmarks. For the class of 2018, 68% and 84% of students met one of more of the ELA and mathematics benchmarks, respectively. The class of 2017 had similar results with 66% and 80% of students meeting benchmarks in ELA and mathematics, respectively. These statistics show that there had been no clear trend in growth of students meeting the benchmarks to correspond with Pathway to Honors, at least within the past three years.

It is important to note that throughout the past nine years examined, there has not been a change of more than 3% in each student demographic category captured in the school report that may have impacted the data captured about achievement. While the intention behind the Pathway to Honors framework is clear, the data around student achievement is difficult to directly link to Pathway to Honors courses based on achievement reports currently available to the public.

“We still have an achievement gap that’s based on race principally, so obviously in a few years, this hasn’t fixed the problem, so the issue remains and there’s obviously more factors that play in that discrepancy,” Livingston says.

Classroom implementation: teachers, students’ experiences

“This was really designed to make sure that we were providing the best possible academic course that we could for all of our students,” Bramley says.

While the intent of Pathway to Honors was to create rigorous educational opportunities for all students at ETHS, the experiences of students and staff members with the model vary.

“Depends on the teachers”

“We want to make sure all students have access to the best curriculum and are stretched as high as they possibly can,” says Leibforth. “But then to have teachers actually do that, to develop the curriculum for that, to teach a mixture of students, you know a lot of that is on the backs of the teachers. So they’ve done an amazing job.”

Parker speaks to a similar value of teacher collaboration to craft and deliver the Pathway to Honors curriculum, recalling specifically her experiences as a history teacher during the implementation of the Freshmen Humanities course.

“I collaborated with my colleagues,” Parker said. “One of the cornerstones of each sort of new course that comes online is to really involve teachers in the discussion, identification of skills and development of the course.”

History teacher Ganae McAlpin notes that the strengths of the Freshmen Humanities course is contingent upon the alignment between the English and history teachers.

“I think a lot of our Honors really depends on the teacher and the teacher pairing that we have,” McAlpin says. “But I think that that is definitely a strength, the pairing of the English and history together.”

The Pathway to Honors classes allow for teachers to adapt the curriculum. According to Slaton, biology teachers now have the freedom to develop their own finals.

“Changes like these allow teachers to create a lot more spaces and content that they are passionate about, that they can get students passionate about,” Slaton explains.

Geometry was the last of the freshman core classes to become a Pathway to Honors course.

“Other departments had already started the Earned Honors model and worked out some of the kinks. Because math is so heavily tracked prior to getting [to ETHS], before students were actually engaged here, we were trying to figure out how we were going to detrack it with the huge range [of students],” Eddy said. “The challenge last year was trying to pace it at a level where the students who traditionally struggle more with the concepts are given enough time. For some students, they just need time to be able to process it and be able to master the concepts.”

“Good intentions”

The perspectives on the intentions and implementation of the Pathway to Honors model were debated among students and families during its original conception, as reported by The Chicago Tribune in 2010.

“After that initial wave, we really haven’t had much resistance or negative feedback,” Bramley said. “It’s maybe a couple of families here and there, and it’s usually something specific to their student’s situation,” Bramley says.

After interviewing several students and conducting a survey taken by 327 students, The Evanstonian found a variety of opinions and experiences, indicating that the perception of Pathway to Honors was not unanimous.

“Earned Honors has very good intentions in that anyone can have more opportunities to obtain an honors credit, “ junior Jade Orbello says. “However, it can go both ways. Honors, I believe, is supposed to be recommended for you because teachers have been aware that you deserve it.”

While some like Orbello are still questioning the principles around earning honors credit through this model, other students see value in the model for all students.

“I do feel Earned Honors is important. Because especially, I’m someone who’s privileged and very lucky to have tools and resources that have helped me very early on to be advanced in a similar kind of studies, but I feel like the kids who don’t have that definitely deserve the opportunity to be on the same playing field,” senior Will Chehab says.

Students have a range of responses to the rigors of the coursework in their Pathway to Honors classes.

“I feel like the classwork is just as it should be, challenging, but not overbearing,” freshman Caron Walker says. “I think [the assessments are] perfectly appropriate because it’s about your comprehension and how well you can understand what you’re supposed to be doing and how well you can apply that understanding to actually doing it.”

Sophomore Ella Greenberg Winnick notes how she did not feel prepared for the transition to AP courses.

“I take one AP class this year, AP Gov., and the main difference I see between AP Gov. and my Humanities classes from last year is that there is a lot more work, meaning you’re supposed to go home, read the chapter, do the work and have a quiz in class the next day,” says Greenberg Winnick. “I just don’t think my Earned Honors classes prepared me for that.”

McAlpin suggests that the Pathway to Honors courses are not intended to be as rigorous as AP courses; however, Pathway to Honors courses can still prepare students for future AP courses if both the teacher and students are aimed towards that goal.

“I think it depends on the teacher. I think it depends on how much work [students] put into it. You know, if you just float through the class, then yeah, no, you’re not gonna be prepared. But if you really do the class, I feel like you should be somewhat prepared,” McAlpin says.

Mallory echoes McAlpin’s focus on student voices and perspectives as they shape class experiences and outcomes.

“I think students can also have that misconception that ‘Well, that was easy. I didn’t really have to do anything,’” Mallory says. “I like to put that back on the students. ‘Well, if you thought that was easy, then what would challenge you?’”

Despite the potential benefits and challenges of this framework, not all students at ETHS currently access the Pathway to Honors courses given the different academic needs they may bring into classrooms.

“We still have a whole other track, which is the support class. And the support students do not get a chance to earn honors. And the support classes are primarily Black and Brown students,” McAlpin says. “So while we are hitting those Black and Brown students who would have been in the regular classes who are now in the Earned Honors class, we still have a nice population of Black and Brown students that don’t even get the opportunity to earn honors.”

McAlpin recognizes the complexities that exist for some of the students in the support class that make it difficult to detrack entirely.

“But I do understand why they have them tracked by ourselves because the reading in the regular Earned Honors classes would be very, very hard for the students in a support class,” McAlpin says.

What’s Next

ETHS is continuing to expand the Pathway to Honors model, adding this framework to new courses this coming school year.

According to Bramley, every class within the CTE and Fine Arts departments that is currently mixed level is moving to an Honors Pathway. This excludes “Project Lead The Way” PLTW courses and AP courses, which have curricula established outside of the school.

“My sense is that in the next five or six years, every class that is not some external course like AVID or Project Lead the Way or Advanced Placement will probably be an Honors Pathway course,” Bramley says.

While initial reactions to the first Pathway to Honors Freshman Humanities course were mixed, the administrators interviewed have indicated mostly positive feedback from students and families about these courses.

However, there are still some enduring questions around the Pathway to Honors implementation and potential improvements that align to the values of this model.

“This is still a work in progress,” Livingston says.