Racial and socioeconomic implications in how ETHS lost its spirit

September 27, 2019

While not the only cause, the demographic diversity at ETHS may play a role in student engagement at school-organized events like dances and sporting events.

The ETHS student body comes from a vast array of households socioeconomically. According to the most recent data available through the City of Evanston, the 2005-2009 ACS Economic Profile shows that 17.5% of Evanston households have an income of less than $25,000 and 36% of households have an income of $100,000 or more. Given this, appealing to the entire ETHS student body when planning school dances is difficult.

ETHS currently has two dances during the year. In the fall, all students can attend Homecoming and in the spring, seniors and invited juniors may attend prom.

“(Prom) is a once in a lifetime opportunity so you’ll go all out. It’s said to be ‘the time of your life’ but not all students have access to that kind of money,” Brecel Limón, a 2019 graduate, says.

ETHS works to make prom more accessible by partnering with Dreams Delivered program, created by the Women’s Club of Evanston, which works to give ETHS students new or almost new prom attire for free. However, prom tickets still cost $150 and students are responsible for their own transportation to and from the event, so the costs add up.

“Prom can be inaccessible for people who aren’t privileged enough to afford to go to school dances, because they chose to have food on the table rather than spend a fortune on one night’s event,” Limón says.

Some students choose to spend money on a prom ticket but don’t even take advantage of everything that comes with the ticket. Despite the fact that the After-Midnight boat cruise is included in the prom ticket price, many students opt not to go on the boat and instead go to after-parties unaffiliated with the school.

According to Boyd, the number of students who go on the boat has decreased drastically over the past few years, which she doesn’t understand.

“You paid for (the boat) and you don’t even take advantage of the thing you paid for,” Boyd says.

Homecoming is a more accessible event as the attire is traditionally informal and tickets cost far less than prom. Tickets cost from $15 to $30 depending on how close to the dance students purchase a ticket.

Unlike ETHS, neighbor school Loyola Academy, which has a socioeconomically homogenous student body in comparison to ETHS, has a formal Homecoming dance. Ticket prices for the Homecoming dances at the two schools are similar, but many Loyola students also spend money on formal attire, a location for pictures before the dance, dinner and transportation to and from the dance.

Loyola senior Betsy Leinenweber approximates that she spent slightly under $200 on last year’s homecoming dance, money that many ETHS students don’t have to spend due to the informal nature of the dance.

“Freshman year, I wore leggings, a shirt, and probably my Adidas,” senior Izzy Kohn says. “I didn’t have to buy anything.”

Like Loyola, Oak Park River Forest High School has a formal Homecoming. OPRF is more comparable in size to ETHS with 3,296 students (ETHS has 3,567 students) compared to Loyola’s 2,052 students.

“People like getting dressed up, especially because it’s our only dance besides prom, which not everyone can go to. If it were less formal, I don’t think as many people would go,” says OPRF junior Lily Manola.

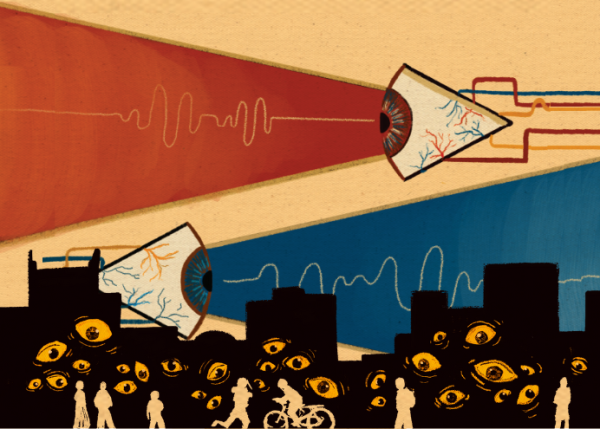

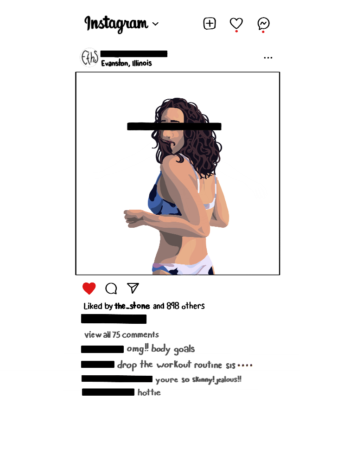

In addition to socioeconomic factors, race may also play a role in student engagement at school events. Friend groups at ETHS are often racially segregated, with many students gravitating towards others who look like them.

According to a study conducted by the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research in 2013, larger high schools “promote racial segregation and discourage interracial friendship.”

“I want to hang out with people of my own race. To be completely transparent, if I come to a new school I’m going to be looking for the black people because I’m black,” 2019 graduate Cynthia Anyaso says.

Anyaso is not the only one with this sentiment. A 2016 study done by the Public Religion Research Institute showed that for white Americans, 91% of people in their social network are also white and for black Americans, 83% of people in their social networks are black.

Given this, the decisions various friend groups make about attending school events can impact the racial composition of the student body attending these events.

“I didn’t go because none of my friends went,” says senior Brendan Long, referring to the Freshman-Sophomore Formal. “I felt like it wasn’t a function sophomores typically go to.”

As aforementioned, formal was canceled because of low attendance. Some students, including Kohn, want formal brought back.

There is also racial segregation at sports games within the student section, especially at football and basketball games. Blue Crew, the group of seniors who paint themselves for football games, has in the past been comprised largely of white students.

According to a 2018 article published in The Evanstonian, “Since its start, Blue Crew has comprised of predominantly white students, most of whom belong to the same few friend groups.”

This year, senior Raven Warlick made a senior group chat to help the senior class come together and avoid the exclusion that has happened in the past.

“I wanted to make sure that this group chat was inclusive to everyone no matter what you look like or what race or gender you are. Everyone is included,” Warlick says.

When trying to better understand student engagement at school-sanctioned events, examining factors such as race and socioeconomics is crucial.