At what cost: what it takes to play club sports

September 28, 2018

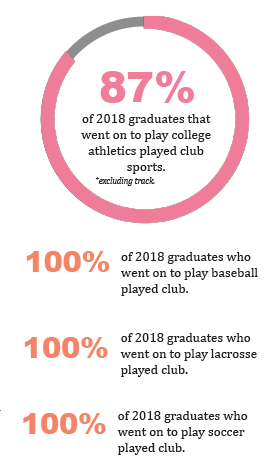

In the past decade, club sports have grown dramatically and have become a dominant part of families’ lives. A 2016 Utah State study showed that the youth sports industry is worth $15.3 billion. Now parents have chosen to start their kid’s sports careers as early as preschool.

“I’ve been playing since I was four,” says freshman and club hockey player Luiza Santos.

According to the 2013 ESPN article on the demographics behind youth sports, money “drives the earliest action” with youth sports. The same data shows that families that earn a yearly income of over $100,000 enroll their children in sports around age six, while families who bring in less than $35,000 yearly begin sports later, around age eight.

Santos plays for the Chicago Young Americans (CYA) U14 girls team, a triple-A hockey club. Playing with CYA takes commitment and time; Santos explains that she travels nine times a year for tournaments. Her team mainly goes to the East Coast and Toronto.

“It is important for people to understand that at the Tier I level, we are at the top of the youth hockey pyramid,” Santos’s coach Frank Bisceglie says, “and the more competitive, in any youth sport, the more expensive it becomes.”

CYA also requires its players to buy uniform gear that includes duffle bags, full warmups, uniforms and helmets. All of the equipment is added to the original price of $3,400.

The top hockey teams come with hefty price tags.

“It’s in the thousands, maybe $10,000,” says Santos.

Though sports like hockey and lacrosse can cost over $10,000, most do not reach that extremity. The 2016 Utah State study found that the average family spends $2,292 annually on sports, and soccer and basketball clubs have an average cost of $1,472 and $1,143, respectively.

Freshman Ellie Oif plays for FC United, a competitive youth soccer team, that costs around $2,700 a year.

Similar to hockey and most competitive club sports, players’ families spend money on traveling. This includes flights, hotel rooms and any additional expenses.

Rob Fournie is the head boys varsity lacrosse coach at ETHS, as well as a coach for True Lacrosse.

“You pay for the club experience, for the club’s coaching, and then if your team travels, you pay for the travel and hotel rooms,” Fournie says.

Comparatively, playing sports at ETHS is typically inexpensive. The costs are usually limited to uniforms. For the girls soccer team, players only bring in $50 for their uniforms, and the school pays for low-income families. Other ETHS sports may use fundraising to help pay for their expenses. Due to last year’s fundraising, the girls golf team got their polos and visors for free this season.

Along with the original price for the club, FC United offers fall training sessions that are $600 for eight hour-long private sessions.

“If you have the right trainer, it’s worth it because they teach you a lot of things,” Oif says.

Aside from the cost, club sports are a huge time commitment. Junior Leo Burg, who has swam competitively since he was around four or five, says that he swims 14-18 hours per week for the YWCA Flying Fish. During his high school season, Burg swims 14-15 hours a week for the ETHS varsity team.

For players with working parents, getting to every practice can be difficult, and taking days off for traveling out of state isn’t doable for all families.

Evanston hockey president Brad Dunlap says that “families look for opportunities to carpool. At the high school level, practice and game times tend to be later in the evening outside of traditional work hours.”

Athletes also tend to miss a lot of school for sports. As players get older, balancing school and their sport becomes harder.

“I miss a lot of school,” Santos says. “I have to sacrifice hanging out with my friends because I have to stay home and study for tests and try to make up other school work.”

The growth that has taken place in club sports hasn’t translated to greater racial diversity of players in the clubs’ teams. The same 2013 ESPN article shows that kids who begin youth sports earliest are primarily white and start sports around age six.

“On my teams, I’m usually the only person of color,” says senior Eudell Watts, who plays for the 1223 Lacrosse club.

When considering how CYA interprets diversity in hockey, Bisceglie explains that CYA hasn’t begun any of their own initiatives for change in racial and economic diversity, but that “providing opportunities for under-privileged children is a top priority in growing the game.”

Olivia O’Donnell is a senior who competes at IK Gymnastics, a club based in Chicago, observes both racial and economic diversity are growing within her sport. However, she says it requires an extremely high level commitment of money and time that can limit access for many athletes.

“Sadly, I don’t think this is unique to just gymnastics, but most club sports,” she said.

Eli Marshall & Jojo Wertheimer, contributors