One March later

A reflection on a year of loss, grief and action.

Like so many, I remember the last time we were physically in school like it was yesterday, yet the time between then and now feels like years. The hallways bustled with anxious confusion, but not enough to stop anyone from being excited about the upcoming two-week break. The words ‘Corona’ and ‘quarantine’ buzzed through the air.

The desks in all the classrooms were separated and bottles of hand sanitizer were positioned by each door. Only a few wore masks and those who did were given sideways looks. The teachers handed us packets of optional work to do that would be able to last us over the next two weeks and then warned us, despite the urge, to not touch our friends.

The weekend before the national COVID-19 shutdown, I went out with my friend. We took the bus downtown and spent the day shopping and roaming the city. There was a weird vibe in the air, like we were all characters in a movie about the end of the world, but of course, it was still fictional right? Almost everyone I knew had gone out that weekend. It was a rebellious last hoorah before the isolation ahead of us.

“I think that it’s something that neither you as a student or I will ever forget, for the rest of our lives. I remember having this pit in my stomach, as students were leaving. We had planned for a couple of weeks, but I just had a feeling that I had no idea when we would be coming back. I hope we never ever, as for my time in education, have to do this again,” Principal Dr. Campbell reflects.

The first few weeks of quarantine were surreal, to say the least. Grocery stores were emptied as people flocked to them, their faces covered in homemade masks and other protective gear, buying everything that would be necessary to sustain themselves. There was a national shortage of toilet paper and the chaotic fear of the unknown increased.

At this point, the U.S. had about 15,000 new Covid cases a week. Hospitals were filling up, and a mask mandate was put in place. Information on the virus was still developing. Doctors, dressed head to toe in PPE, described the situation as scary and surreal.

“A lot of my friends were high risk and they were all kind of just in a panic about whether or not they were going to be okay.” Junior Kiki Martinez says. “I tried not to have any contact or in person connections with anyone because of the fear of getting sick.”

Meanwhile, Tik Tok and viral trends like whipped coffee, the renegade, bread baking, and Tiger King consumed our attention.

“I remember before quarantine I didn’t like Tik Tok at all—like I disliked it heavily. And then my sister said ‘go on and download it’ two weeks into quarantine, and now I watch it nearly every day.”

After dinner, we sat on our couches and watched celebrities in their living rooms sing songs about perseverance and togetherness. We basked in our shared experience but envied the advantages their lives of fortune gave them. On our windows, we hung hearts for health workers and teddy bears for the local neighborhood kids to find on their daily family walks.

“I began helping a lot more around the house, and reading a lot more, and just trying to work on my own mental health as much as possible,” Martinez says

To celebrate, birthdays, graduations, anniversaries, and all monumental moments, families were forced to be creative and planned drive-by parades and celebrations. Caravans of cars filled with friends and family beeped their horns and waved signs from a distance. It was a strange reality and a huge difference from what would otherwise be occasions marked by large gatherings and hugs. In addition, many graduations were held over zoom. This was crushing for many students who had worked so hard for so long and weren’t able to have a momentous moment to mark all their work, but they also showed resilience and positivity, refusing to let their situation bring them down.

“I wasn’t really able to have an actual eighth-grade graduation. The staff of Haven, my middle school, worked together to put all of the graduation stuff together in a slide show that we were able to access the day of the graduation. Of course, it was disappointing that we weren’t able to have one in person but I didn’t really mind that much,” says freshman Emerson Mann.

School was a whole other obstacle in itself. Classes slowly began to switch online. Classrooms became computer screens, textbooks became websites and commutes became rolling over in bed. The newness of this reality was a shock to everyone’s system. School didn’t feel mandatory but the stresses of grades and test scores still existed. Managing these new stresses within a new reality was very difficult, and, for many students, mental health began to take a toll.

“I knew the second they told us school was going online that I was going to struggle keeping up with my schoolwork. For me, and a lot of people I know, we burned out pretty quickly. The end of the year was just very low effort, and very difficult for a lot of us,” senior Lina Kodaimati says.

The new challenges in education extended beyond classes at school; they had crucial effects on standardized testing, which can often affect students’ chances of getting into college.

“[Taking the AP exams] was not an easy process for a lot of people, especially because of internet difficulties,” Kodaimati says. “The ability to apply to college also changed in a variety of ways. In my experiences, especially because my parents are immigrants, I didn’t have help for the college application process. It wasn’t readily accessible for me to go talk to a teacher or talk to my classmates about it. So it was difficult for me to navigate that.”

Eventually, spring merged into summer, and the days finally began to slightly differentiate. At this point, the U.S. had about 50,000 new COVID-19 cases a week. Now that it was warm enough, seeing friends outside became an option for many. In response to newfound gatherings, Chicago beaches and other similar places closed in an attempt to stop large influxes of people and keep transmission rates down. Despite the dramatic everyday increase of COVID-19 cases, hopes for returning back to school in the fall increased. The warm weather made it easier to deny the reality in which we were living.

“I was able to participate in tennis camps wearing masks and being socially distanced. Most of my summers I spend outside anyway with my friends, so being able to hang out with my friends outside felt like the most normal thing I had experienced since March,” freshman Emerson Mann says.

In response to the national mass job loss created by the pandemic, the government issued stimulus checks in an attempt to help those struggling financially. Some checks were received right away, while others had to wait weeks and even months for theirs to arrive. For many this meant, rents, utility bills and even groceries could not be paid.

Alongside the globally prevalent events of COVID-19, an 8 minute and 46 second moment caught on video held the world’s attention. On May 25, in Minneapolis, a Black man named George Floyd was brutally murdered by four police officers. As he struggled for life, the words “I can’t breathe” could be heard clearly both by the officers and the millions of people who later watched this moment of horrific violence that undoubtedly reflected the racist realities of American policing.

This was not an isolated incident. Undeniable similarities between George Floyd’s murder and those of Breonna Taylor, Tyree Davis, Michael Brown, Lauqan McDonald, Tamir Rice, Ahmaud Arbery, Elijah McClain and many others were noticed and brought to attention.

“It was definitely a scary time. George Floyd’s death was completely horrifying and disgusting.” Mann says. “[But] when the protests started happening and Evanston started holding them as well, it was super amazing to see everyone come together and protest for what’s right.”

“I felt powerless, in a way. Signing petitions does something, but it never does enough,” sophomore Sophia Hogue says, “I wanted to protest because, to me, things like signing petitions don’t feel as strong as coming together with a community.”

These events, and the centuries of systemic racism that had led to them, ignited a mass movement against police brutality, not just in Minneapolis but around the world. Despite Covid restrictions and stay-at-home orders, people gathered in support of Black lives and the abolition of police. Millions worldwide took to the streets chanting “Black Lives Matter.” The protests lasted for weeks, many of which were led by youth and student activists. There was at once a collective energy and a desire for change.

As a result, one of the police officers responsible for George Floyd’s death was charged with second-degree murder and the others with aiding and abetting, Minneapolis vowed to disband its police department, the Mayor of New York vowed to move police funding towards youth and social services and many states reviewed police reforms. However, the movement against police brutality still continues.

“It’s really difficult to try and fix anything because of the way some people have reacted to it. Right now, all we can do is show our support and hopefully that will show others [who are affected by this] that we want to stand beside them,” Martinez says.

Eventually, fall came, and with it, the decreased hope of schools re-opening. The leaves began to turn and the days slowly became colder. Being outside became less of an option and we were once again forced to remember the realities of quarantine. At this point, the U.S. had about 40,000 new COVID-19 cases a week.

School started back up fully virtually. Students once again began to log into Zoom and Google Classroom. For many students, sitting in front of the computer for 6-plus hours a day became exhausting, and stress levels rose.

“My mental health started getting worse around September or October of 2020—right when school started,” sophomore Sophia Hogue says. “It’s not only mental illness; it’s also the struggle with a lack of motivation, feeling like you have to procrastinate everything or feeling like everything is just so overwhelming and intense anxiety and depression. I see so many more people struggling with depression and anxiety now.”

Once again, social interaction and connection became extremely limiting. Students were expected to fully engage in class and the curriculum, but without the physical presence of a teacher, attention levels and overall academic performance continued to decrease as the weeks in full remote learning went on. Staying motivated was a new and never-ending challenge.

“Sitting at a computer multiple hours a day takes a lot out of you. At the beginning of quarantine it was very boring but you still had life going on. Now, it just feels like this is everything.” Hogue says.

November marked the election and a monumental one at that. The month was filled with news streams, poll watching and anxious energy. The country’s political divisions were as apparent as ever. Issues like immigration, police brutality, climate change, the right to choose and the coronavirus were all up for debate.

“A lot of my friends were worried just about their rights as human beings, which is something you should never have to worry about. I know that I couldn’t focus on my school work the week before the election; it was very difficult in that sense,” Kodaimati says.

On Nov. 7, President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris won the presidential election, making Harris the first woman and first POC to hold the position. A majority of the country celebrated the victory that would mark the end of Trump’s presidency. The streets filled with people singing songs of joy, church bells rang and many happy tears were shed.

Meanwhile, the other part, angered in disbelief, refused to accept the results of the election. They claimed that it was “rigged” and a fraud, saying that Trump really did win. Trump backed his supporters’ false accusations and even went as far as to encourage them to storm the Capitol and defend their believed victory.

And that they did. On Jan. 6, days before Joe Biden’s inauguration, thousands of Trump supporters, dressed in MAGA gear and confederate flags, broke into the U.S. Capitol building, stealing podiums, trashing offices and threatening members of Congress. It was an unprecedented event, and reporters called it “a threat to democracy.”

“The Capitol riots were awful. This was one of the many things I had never seen happen in my life and it was honestly scary.” Mann says.

“One of the most infuriating things about the riots was the stark contrast they presented to the Black Lives Matter protests over the summer,” Martinez explains her frustration at the treatment of the insurrectionists compared to the violence used against BLM protesters. And, furthermore, the lack of safety precautions at the riots showed a blatant disregard for public safety, as well as highlighting the effects of anti-mask rhetoric within the Republican party.

“People have this thought that ‘it’s a free country, I’m going to do whatever I want; I’m going to put other peoples lives at risk,’” Skinner says. “Because that’s what not wearing a mask is,” he explains, “a risk to all of those around you.”

Following this event, Trump got banned from nearly all social media platforms, including Twitter, and Vice President Pence publicly defied Trump’s orders to continue denouncing the election results. Meanwhile, by this point, the U.S. had about 250,00 new COVID-19 cases a week.

We entered winter, and the new year at an all-time high of COVID-19 cases. Illinois Governor Pritzker and Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot issued another stay-at-home advisory. This, combined with the cold and constant snow, kept us inside and once again isolated.

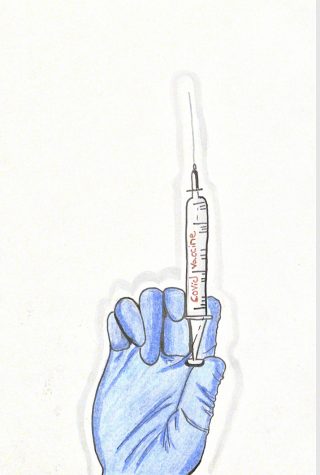

However, hope was around the corner. Pfizer and Moderna released their COVID-19 vaccines, and the rollout began. It seemed like there was finally a light around the corner. First responders, healthcare workers, elderely, teachers and others began to be vaccinated.

“When I first found out that we were going to get a vaccine this year, I was like, ‘whoa, you mean, I actually might be able to do the musical. I might actually be able to Yamo.’ So, I was pretty optimistic.” Skinner says.

Unfortunately, the process to be vaccinated was not easy. People had to navigate the rollout plan and the difficult online registration process, making accessibility challenging. New vaccines, however, did not mean an automatic shift in the everyday life of living in a pandemic. The hope was met with a harsh reminder of how time-consuming and loss-inducing COVID-19 has been and will continue to be.

“We actually are getting access to getting the vaccine where I work since we’re food providers. But, currently, every pharmacy that I’ve reached out to has already had a full schedule. They’re having difficulty vaccinating everyone. Having the first round of the vaccine and then having to go back for the second round is difficult when everything is being rushed.”

On Feb. 22 the U.S. hit 500,000 COVID-19 deaths. President Biden lined the White House lawn with flags to commemorate lives lost and held a moment of silence to honor those who had passed at the hands of COVID-19. It was a shocking and heartbreaking moment that held us all together in grief.

Now, it’s March, and the term “social distancing” has become a natural part of our vocabulary, masks feel normal and part of our everyday attire, standing six feet apart no longer free strange and the circles on floors to stand in and plexiglass separating us in public spaces no longer seem out of place. This once-dystopian-like reality has been accepted, and we have adapted to its presence.

This month marks a year since the world shut down. A year of washing our hands and wearing masks, of fearing the outside world, of not seeing friends and family, of isolation and anxiety and Zoom calls—but also a year of shared experience, mass political change and, most importantly, gratitude. Gratitude for what we have and an appreciation for everything we once took for granted.

After a year of loss, sorrow, violence and anger, some young people have begun to feel desensitized. We have witnessed so much pain that, in a way, it has begun to feel commonplace.

“It’s very difficult to keep up with seeing so many horrible things and have to put effort into each one of them. Especially having to hear about things that personally affect me. It’s just not really a good situation to be in that mindset constantly,” Kodaimati says.

“It’s hard to be empathetic when you hear the same thing all the time,” Hogue says. “I feel saddened, but at the same time, it’s so repetitive. I think we’ve really become desensitized as a society.”

But we have, as a community, also found a way to share empathy. We’ve looked around at the changing storefronts, changing workplaces, changing families, and we have decided to make the best of it.

Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.