Gatekeeping activities: the damage of stereotyped experiences on Black youth

So many activities at ETHS—including the Evanstonian—have barriers, ones that are grounded in white supremacy, that keep BIPOC from feeling comfortable entering into these spaces.

February 22, 2021

There are countless school-endorsed activities and sports in which students can indulge from a young age. From chess to football, having an activity that evokes passion and joy is a beautiful way to enjoy childhood. It is evident through even taking a glance at club and team photos at ETHS, however, that there is a lack of Black youth in many activities and sports, such as the Evanstonian, ETHS musicals and plays, sports and more.

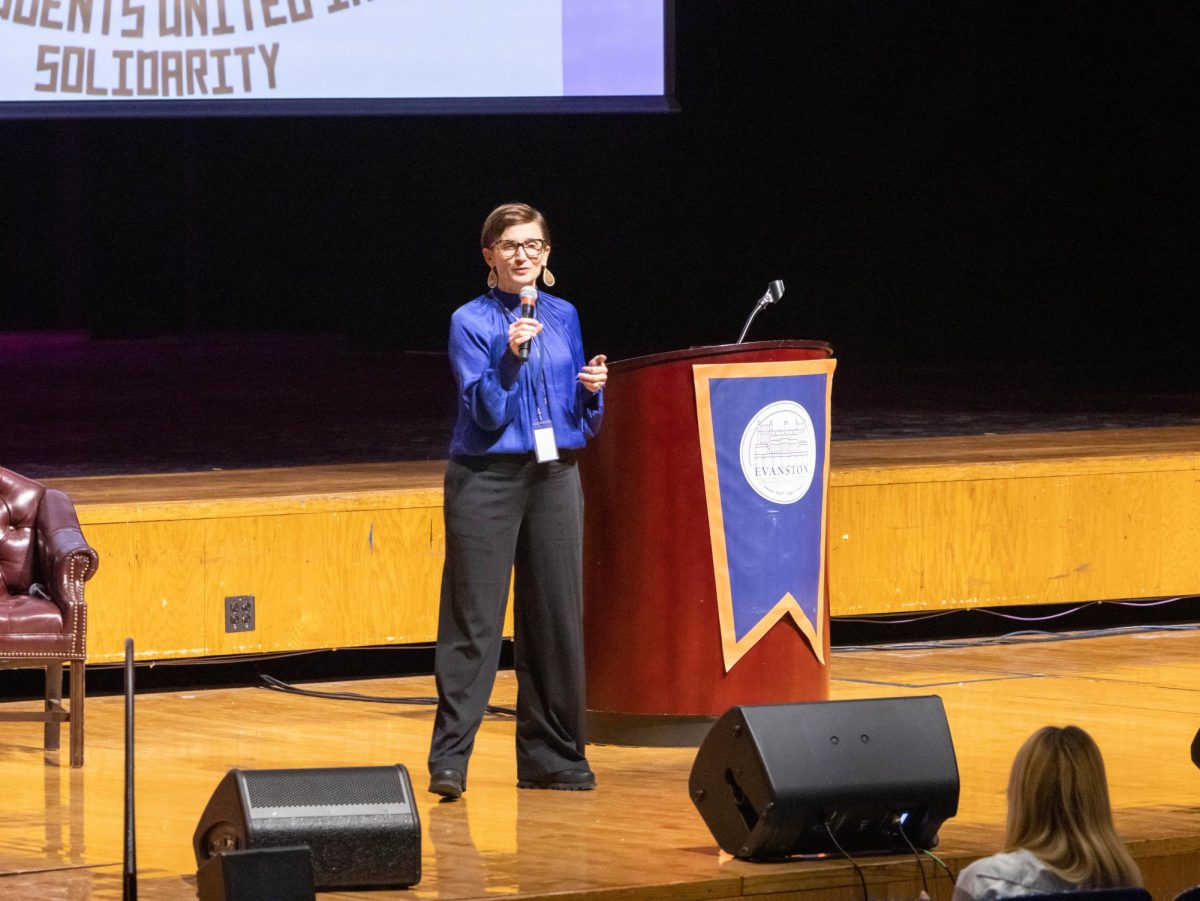

“I think that the Evanstonian and a lot of other spaces have felt very white and have been very white,” Assistant Superintendent and Principal Marcus Campbell explains.

So, why, at every turn, can we never see ourselves represented in school-sponsored, co-curricular, extracurricular and athletic programs?

This is a question that administrators, teachers, parents and students wonder constantly. Well, Black folks have been experiencing the damage of racial stereotypes, in addition to the struggles that come with being a minority, for a very long time.

“That’s really important from a systemic piece, but also from a school culture piece. [I’d ask], ‘Why don’t more students of color feel like they could be and should be involved in these things? And if they do, and when they show up, will their voices be heard? Will they be seen? Or will it be another space full of microaggressions?’ We’ve been working to address that. It’s come up in a lot of conversation with a lot of staff members and kids. I sit with some other boards as well answering this very question,” Campbell says.

Although ETHS tries to combat this reality, institutionally, we’re told we’re not “enough” of our race if we don’t fit into the stereotypes that were created for us. We’re told that we’re “acting white” if we excel in school or participate in predominantly white activities.

“While we’ve gotten to the point of having different spaces for different affinity groups to be seen, I don’t want to say that we’re not doing a good job; I just think that there’s [more] we can continue to improve,” college and career services specialist Llyoandra Cooper explains. “As we talk about the things that we see, the issues with equity, the issues with respect, in showing the spaces and giving safe spaces for affinity groups, I think we can do more. I think there are still some spaces that are overwhelmingly [white] majority [where] there’s no diversity in those spaces—whether that’s the debate team, whether that’s the Evanstonian—I think there’s a lot of spaces where they’re still not as diverse as the student body and as the Evanston community.”

These truths are just a few factors that feed into the lack of Black youth in predominantly white activities. Imagine this: Raina is a young Black girl who is just starting her freshman year at ETHS. She is amazing at playing the violin and really wants to join the orchestra. However, she is torn between joining or not because of the lack of diversity. If she joins, she won’t feel like she belongs in a space with few to no people who look like her. She may also get made fun of by her peers for “trying to be white” since she’s a part of a predominantly white activity and has mostly white friends because of the friends she’s made at orchestra. She also noticed that it is mandatory for students to wear their hair in a style that is not inclusive for Black folks.

“We are fortunate enough to be in a community, ETHS, where we have an abundance of resources. However, with that abundance of resources comes the understanding of how to access resources,” Cooper explains. “Education is not something that starts [at] an endpoint or institution. It’s at home. Home should be the first place where it starts. When we talk about access and a toolkit, who has what tools? We have to look at it from that standpoint, and then [if] we’re going to talk about disparity, [if] we’re going to talk about socioeconomic status and [if] we’re going to talk about language and education in the home.”

These imagined experiences that Raina will have if she joins become enough for her to not join orchestra, an activity that she had been absolutely passionate about prior to high school.

Contemplating whether we should do an activity because of the color of our skin, because there is nobody else that looks like us, should not even be in question. We live in a society where stereotypes are so normalized, subtle and ingrained in our everyday lives that it’s hard to avoid the contemplation. This can be extremely damaging for Black youth and lead them to refrain from doing things they love to do.

As a school community, we have to be eager to welcome every student and give Black students the same opportunity to express skill regardless of the lack of diversity a group might have to begin with. Intentionally welcoming Black students into spaces allows a level of comfort that comes with being around people that look like you and understand you. Understanding each other, expressing our personal talents, even if they are initially out of our comfort zones, must be normalized in all communities at ETHS.

We need to normalize bravery. And allowing us to feel confident enough to step into a predominantly white atmosphere and prevail can define that welcoming space. It only takes one person to cause a domino effect. Campbell reiterates this when explaining what he has told students of color who hoped to participate in an activity that they loved but was predominately white.

“[I would say] ‘Yes, you know, it can feel very white,’ and talk about Courageous Conversations; you don’t have multiple perspectives sometimes. You have to think about it as a space that you really want to be in. [I would ask] ‘How do you speak your truth and work with the sponsor to make sure that it’s the space that it needs to be?” Campbell explains. “I think about so many people of color who have pioneered in spaces that did not reflect them. I think about Kamala Harris, and so many others. I wouldn’t dare tell a kid, ‘All right, you need to go find someplace else.’ No, stay there and be the voice for truth and be the voice for yourself. Make the space your own, because you have a right to be there just like everybody else.”