Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

A brief history of the Evanstonian

February 22, 2021

To reflect on the current ways in which the Evanstonian subconsciously perpetuates white supremacy and what a future of actively fighting against this looks like, it is crucial to first examine the publication’s history. How has the student-run newspaper covered stories surrounding race since its creation in 1916, specifically focusing on the past 40 years? How have Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) students been portrayed and represented compared to their white peers in both the staff and the coverage? Upon reflection, what stories and coverage of events are worthy of critique?

The answer to these questions lies in the alumni. The Evanstonian has produced over 360 issues since 1980; it would take eons to comb through every single publication since then. Even then, we’d have no clue what the reception was to said articles. But, nothing illustrates history more than the respective truths and realities of people who experienced it.

1980s

“When I was there, I think when I was a junior, there was a big issue, an issue that was devoted solely to race relations at ETHS. I would love to go back and read it… I just remember it causing a lot of discussions. It was a really big deal,” class of 1981 alumn, Diane Goldring, explains.

Goldring was a writer and features editor of the Evanstonian and is a current candidate for Evanston’s 4th Ward alderperson.

“I will remember very well there was one controversial piece. In about 1981, [the Evanstonian was] talking about race relations, and there was an article that came out that was somewhat stereotypical towards African Americans. We were so offended. We kind of marched to the office and said, ‘Why would you write things like this about us without even talking to us?’” Yvonne Taylor, also class of 1981, explains.

And so, on a Monday afternoon, the dusty copies of past Evanstonian newspapers stored in the back closet of room S103 were dug through until the issue in question was found, and the investigation continued.

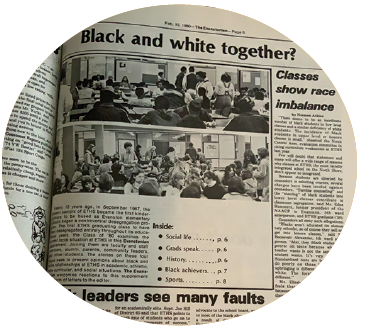

On Feb. 15, 1980, the Evanstonian released an entire special pullout titled “Black and white together?” solely focused on discussing “race relations” at ETHS.

“The first ETHS graduating class to have been desegregated entirely throughout its educational years, the Class of ‘80, examines the current racial situation at ETHS in this Evanstonian supplement… the stories on these four pages seek to present opinions about black and white relationships at ETHS in academic, athletic, extra-curricular and social situations. The Evanstonian welcomes reactions to this supplement in the form of letters to the editor.”

A noticeable aspect of this issue is that the journalists clearly tried to remain unbiased and did not comment on what any of the quotes said. One anonymous letter written to the editor even praised this.

“I thought that your Feb. 15 issue… was very well done on the part of your staff… The writers’ views remained unbiased and professional.”

Taylor clearly remembers the issue’s reception at the time and how the Evanstonian navigated the ETHS community.

“The Evanstonian back then was almost an exclusive club. It was almost like they didn’t want to hear from you. It’s kind of sad because, in my experience of ETHS and Evanston globally as a school, we really embraced each other, no matter what walk of life we came from. Well, when it came to the Evanstonian, you went there and you want to work for them… [they said] no,” Taylor says. “It wasn’t open to us. They didn’t want to hear from us. They wanted to say what they wanted to say, how they wanted to say it until that piece got them slapped back in the face. They thought that they could just do and say what they wanted to. It was almost to the point [where they thought] ‘Oh, Black people don’t even read.’ Well, yeah, BAM! We do. It was ugly. That was ugly.”

“The Evanstonian back then was almost an exclusive club. It was almost like they didn’t want to hear from you. It’s kind of sad because, in my experience of ETHS and Evanston globally as a school, we really embraced each other, no matter what walk of life we came from. Well, when it came to the Evanstonian, you went there and you want to work for them… [they said] no,” Taylor says. “It wasn’t open to us. They didn’t want to hear from us. They wanted to say what they wanted to say, how they wanted to say it until that piece got them slapped back in the face. They thought that they could just do and say what they wanted to. It was almost to the point [where they thought] ‘Oh, Black people don’t even read.’ Well, yeah, BAM! We do. It was ugly. That was ugly.”

After reading some of the articles, the staff’s attempt at neutrality was a major cause of the conflict that followed.

One article that discusses race within athletics at ETHS, “Self-imposed color barrier?” by Dan Newman, starts right off with a quote from ex-football coach Dick Mahoney.

“Blacks are not as disciplined as they could be and they don’t respect authority as much as they should.”

This quote is clearly racist, perpetuating a harmful stereotype that can be traced back to slavery and that now manifests itself in the school-to-prison pipeline and the prison industrial complex (PIC).

Newman did not expand on this comment, however, or discuss the harmful implications of that perspective. He simply gave room for the quote (the very first line of the article) and moved on with the piece.

This is an unacceptable way for journalists to handle coverage of topics surrounding race. By not challenging the quote, Mahoney’s statement was validated and made to be a fair perspective to have. By not challenging the quote, Newman gave the statement power.

Doubling down on this validation, the Evanstonian published a letter from Mahoney two weeks later, in which the ex-football coach claimed, “It is very disappointing when statements are taken out of context, made to mean something that they were never meant to mean, and used to elicit a response that a few people desired.” Clearly, Mahoney’s comments—which were validated by the paper itself—had not been received kindly by readers. Yet, the publication still continued to provide space for Mahoney to backtrack his remarks.

It must be understood that one can not remain unbiased or neutral about racism; it cannot be treated like a conversation about which ice cream flavor is best. There is wrong, and there is right; there is racist, and there is anti-racist. Referencing back to the school-to-prison pipeline and the PIC, lives are literally put at risk when these harmful perspectives are given a space to breathe and a platform to share.

A way to combat this is through research. Race is a very complicated and layered topic, and it requires a lot of effort to fully understand the history behind stereotypes and seeming realities, especially for white people. If the staff truly felt that they wanted to give voice to multiple perspectives, even though we have already discussed why that can be harmful, the least they could have done was to provide some background on the systemic reasons behind why the majority of Evanston’s Black population at the time was low-income, or why Black students had/have disproportionately low standardized test scores compared to their white counterparts. Context is crucial.

There are more instances of un-checked racism throughout the publication.

“To my knowledge, that’s what caused a lot of backlash on that particular piece because it’s like ‘You don’t have enough of us there to really make that type of assessment!’ I do remember quite a few students crowded the door, and we were just demanding retractions. It was a big deal. People were, excuse my language, but we were pissed. Like, ‘Who are you to say this about us?’ [There were] not a lot of African Americans on the paper. It was, I would say, 90 percent white. No, I would say 97 percent white,” Taylor explains.

Another prominent issue throughout is the lack of perspective from non-white students. This shows up in two forms; through the majority-white staff that published this issue and through the people that were interviewed.

The race of the writers and the interviewees is rarely mentioned in the newspaper. However, a letter sent to the editor by then-senior Jill Adams, published in the Feb. 29 issue, confirms the lack of non-white representation.

The race of the writers and the interviewees is rarely mentioned in the newspaper. However, a letter sent to the editor by then-senior Jill Adams, published in the Feb. 29 issue, confirms the lack of non-white representation.

“It upsets me that you and your staff did not find it necessary to have any blacks consulting or contributing to the issue. The 100 percent white senior staff decided to do an issue on the race problem and yet ignore the chance for any black input into the form or structure of the section. Yes, you did interview blacks, but blacks have no control over the topics or what was to be printed… you could have asked blacks to do volunteer work on the section or even suggest topics. I know a number of black students who would have helped. If you were going to do an issue on blacks and whites, then I feel that it was your responsibility to make sure that your paper and staff could not be considered biased because only whites controlled the outcome… By ignoring the fact that you had a problem and that blacks could have added to your section, could it not be said that the Evanstonian is guilty of the same racism it attacked? One should always put their own hour in order first.”

Although she graduated before the Feb. 15 issue was published, Marlyn Sogliln, class of 1978 and career journalist, comments on the importance of diverse perspectives within any publication.

“With more people of a diverse nature, you have more diverse stories. And otherwise, you tend to follow things that are much more white-male-dominated, and it’s sad,” Soglin explains.

It can not be stressed enough how important it is to have multiple communities represented in the writer’s room. There is no doubt that, with a majority white staff and interview pool, coverage of any number of topics will end up layered in bias and blindspots. As stated previously, countless amounts of unchecked racism, both from the journalists and interviewees, are going to make it to the printing press if there is no one to share a counter argument based on their own experiences. When it comes to telling the stories of struggle or joy that BIPOC students face at ETHS, it must be under the control of said students if and how we want to share our truths. If not, as displayed in this issue and countless others, racial communities can be portrayed as homogenous, harmful stereotypes can be reinforced and the result will only increase the “othering” of BIPOC.

Another aspect of this issue that stands out is the erasure of other non-white communities at ETHS. It is even in the title of the issue, “Black and white together?”

It is crucial to acknowledge that Blackness is racialized in a way unique to every other racial group. And, it can be argued that the point of this issue was to specifically address the relationships between students who were Black and those who were white, centering Blackness and whiteness in relation to each other. This is a valid argument.

Due to the lack of articles that represent other racial communities in previous or following issues of the Evanstonian, however, one can not help but wonder whether that was truly the thought process of the journalists who put together this collection of articles. More likely, it came from a racial Black-white binary mindset that has roots in anti-Blackness and centers Black and white as the two main races. This concept will be further explored in the Present section of this issue in the article titled “Binaries.”

In a publication that claimed to examine “the current racial situation at ETHS,” not including the stories of BIPOC alienates students who do not fit into the Black and white binary. This in turn invalidates their experiences.

Laura Fogelson, a sophomore at the time, wrote a letter to the editor addressing this.

“You dealt with an extraordinarily delicate subject and didn’t handle it delicately enough. If you are going to write about one race, you should write about all of them. How many other minorities are in this school? There are not just blacks and whites… You were the ones thinking only of “salt and pepper.”

As ETHS so proudly likes to preach, it is a diverse community full of students of all races. And, while there are no accessible statistics of the school’s racial makeup in 1980, this quote proves that it was also a reality at the time. When addressing the large umbrella term that is racism, it is crucial to include the voices of all races; while each person within the same race does not have homogenous experiences, the experiences of each race in comparison to each other are unique and needs to be acknowledged.

While it is impossible to look through every article since 1980, there is something to be said about how we were not able to find any articles surrounding the experiences of non-Black and non-white students at ETHS in any of our searches.

It is commendable that the Evanstonian tried to open up space for a conversation surrounding race at ETHS, though it required more thoughtfulness and perspectives. Overall, there are clearly many places for growth when looking back at the 1980s.

Following the publication of this issue, it was decided in the spring of 1980 to eliminate the required 3 English Journalism Honors class that all writers for the Evanstonian had to take before being able to join the newspaper in an effort to make access to the publication more equitable.

1990s

The Evanstonian changed tremendously from the ‘80s to the ‘90s.

“When we said something that was important to us, we knew it was going to be in the paper; it was going to be talked about. It was going to be written in a way that reflected students’ opinions. It was just so cool; I always remember it always being such a cool paper,” class of 1990 and current librarian at ETHS, Traci Brown-Powell, explains.

Brown-Powell additionally felt a sense of unity surrounding the publication.

“We had a student center where all the juniors and seniors came, Black, white, Asian, what have you, so we all heard the story there, we all felt inclusive there, you know, it wasn’t closed off. But we had something to say. It wasn’t like it was a white publication for all the white kids and it was only their issues on there. We talked about a lot of social issues that affected the entire student body,” Brown-Powell says.

Karen Jordan, also class of 1990 and current weekend anchor for ABC-7 Chicago, shares similar positive memories.

“Some people wrote editorials about, like, ‘How would you feel if somebody white wrote [that]?’ The paper was sort of an outlet to air out people’s opinions and sparked dialogue. So I felt like it was very much supported and embraced by the student body,” Jordan explains.

Proximity to the paper appears to have had a large influence on people’s views of it, however. While Brown-Powell had friends on the paper and Jordan was on it, current ETHS math teacher and class of 1992 graduate Andrew Segall had a slightly different experience than Brown-Powell and Jordan in terms of inclusivity.

“I rarely found myself reading things that spoke to me. I don’t really recall thinking to myself, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s this article I have to read.’ I don’t think I intersected with whatever the paper was writing at the time,” Segall says.

“I would say the Evanstonian is kind of like, if you looked at it like a members-only club,” Joe Martin, class of 1998, similarly summarizes his experience.

Brown-Powell and Jordan’s experiences in contrast with Segall and Martin’s highlight the disparity in experiences and perspectives, illustrating how important it is to constantly seek out the experiences of all members of the student body, not just a select few. However, it is refreshing to see progress in comparison to the ‘80s when talking candidly about race and welcoming more perspectives.

Looking through the March 1, 1991, issue of the Evanstonian, this openness for conversations directly discussing race is clearly displayed. These articles do not try to be unbiased similarly to ten years ago; they take a firm stand against racism.

One article, titled “Rhetoric Dept.” by John Ennis, attempts to familiarize the audience with racism, appearing to speak to a primarily white one.

Ennis tells the story of a kid named Dwight, who is “in no sense a minority; he was the typical white male.” After taking on the appearance of a “headbanger,” growing his hair out and taking on other “grungy” traits, “Dwight’s plight with discrimination began.” He was accused of being on drugs and assumed to be an underachiever, among other things. Therefore, according to Ennis, “Dwight knows a microcosm of racism”.

“When you distrust someone you don’t know, primarily because they are a different color, wear different fashions, or smell differently, it’s discrimination. Racism is the fear or hatred of all people of a race. Racism is thinking that all black people are the violent poor people of America’s ghettos. Racism is thinking that all white people are rich snobs with disregard for others outside their social circle. Racism is thinking that all Latinos are lazy underachievers. Racism is thinking that all Asians are cold, unfeeling scholars. These conceptions come from lazy thinkers.”

This article is well-intentioned, but it lacks depth in terms of research and misses the mark about addressing racism.

When defining racism, it is crucial to understand that it is a systemic power structure that specifically oppresses BIPOC and works in favor of white people. People who are white can not be the victims of racism. Saying so makes it appear as though BIPOC and white people are on the same playing field and deal with the same struggles in relation to their race. It disregards the impact of white supremacy. It disregards the intergenerational trauma that many BIPOC communities have that results in an unavoidable sense of mistrust towards white people. It disregards the continuously lived experiences of many BIPOC that have proven time and time again that there is sometimes no other choice but to act with a bit of caution around white people.

When defining racism, definitions created by BIPOC scholars and activists must be researched and prioritized before writing what simply sounds right from a white perspective.

Ennis’ piece does hold pockets of truth that a fair amount of white Evanstonians could still learn from, however.

Ennis’ piece does hold pockets of truth that a fair amount of white Evanstonians could still learn from, however.

“Avoiding racism is like recovering from alcoholism—the first step is admitting that you have a problem.”

While there was still immense room for growth in the 1990s for the Evanstonian, it is noteworthy that these conversations were had more frequently and that journalists had the space to write candidly and intentionally about racism.

“[The Evanstonian] just taught me to think more critically and observe life instead of just sort of going through it and not really paying attention. [I learned about] being patient, [the Evanstonian] encouraged me to be a more curious person,” Jordan reflects.

2000s

“I’m really glad that the newspaper seems to be more about what’s actually happening in the school, like classes and what kids think about them, rather than, when I was there, we were talking about where’s the best place to eat a hamburger,” Alex Brown, history teacher and class of 2004, explains.

Current college and career services staff member Llyoandra Cooper, class of 2008, shares a similar sentiment.

“Diversity back then looked very different for us. It just looked different; we weren’t really talking [about it] in terms of race relations and diversity and equity. If you think about [it] like a plate, that was a side dish. These days, it’s like the main course. We knew those issues existed; we knew things were there, but it wasn’t really as prominent,” Cooper explains.

While it was surprisingly tricky to find copies of issues from the 2000s, we were able to find one from Nov. 6, 2009, that includes a piece titled “They fought the law, the white girl won” by Carolynn Pelletier.

This article addresses the drastically different encounters and outcomes that Eugene Mason, a Black senior, and Ellen Roeder, a white junior, had when they interacted with the Evanston Police Department. Mason, licensed, was pulled over while driving for having an expired sticker, thrown onto the ground by the police and received 25 hours of community service along with a $250 fine. Roeder, unlicensed, took her parents’ car and crashed into four parked cars, flipped her own and walked away with a clean record and her license obtained six weeks later.

This is an incredibly important story to tell and comparison to make, yet this article does not dive in deep enough. The ten short paragraphs only take up a quarter of the front page, and the larger issue of an inherently unjust criminal justice system is barely mentioned. If the Evanstonian is going to bring awareness to unjust realities, which it must, it also needs to provide a thorough background of the history behind said act of injustice—in this case, racial profiling—and its present implications. It cannot just include a brief quote that says:

“The two situations seem to indicate class and racial inequality in the legal system,” and not expand on it. Readers are then left to think it is not an issue that requires more attention and a thorough understanding to combat.

Reflection

It is important to clarify why we found it important to reflect on the Evanstonian’s past coverage of topics surrounding race and the representation of BIPOC students. How are articles written 40, 30, 20 years ago relevant to the publication today? Were they not just different times with obvious growth since then?

Well, why do we study history? Not to remember the specific date that Abraham Lincoln was murdered or the number of soldiers that died during the Civil War. We do it to notice patterns from the past; observe what has worked and what has not; what has changed and what has not; which communities were harmed by an event; which communities benefited from an event; why things are the way that they are today. Because, to make meaningful change, we must comprehend the systems that resulted in the need for this issue to be created in the first place.

When ETHS was founded in 1883, it was founded under the system of white supremacy that was enforced through racist teachings and segregation. Due to this being ingrained into the school’s roots, it continues to be a structure that the school must actively fight against. When the Evanstonian was founded pre-integration in 1916, it fell within this larger ETHS system and therefore has white supremacy sewn into its roots. We must understand this past to be able to reflect on the present and dream for the future.

Michael DeVaul, who graduated in 1979, one year prior to the Feb. 15 issue of 1980 that was received critically, comments on how integration played a role in the student body’s perception of diversity within the school.

“I think that high school was at a time [where] we would transcend race, and the Evanstonian was also a place for that. But when we really talk about it, it wasn’t as diverse as we think it was. It felt more diverse because we were on the cutting edge of integration,” DeVaul says.

The most notable observation that has unfortunately stayed consistent is the lack of staff who are BIPOC in the Evanstonian. The newspaper has a history of being elitist and unwelcoming, and this is something that will be thoroughly explored in the Present section of this issue.

Another consistent pattern is the lack of representation for students who do not fit into the Black and white racial binary. As previously stated, each non-white race faces its own unique realities. Without any representation surrounding these realities, the lack of awareness perpetuates a homogenizing culture that benefits white supremacy.

We can also conclude that research and thorough contextualization is crucial for the coverage of topics surrounding race. Racism is a complex system that has a purposefully hidden history, and many harmful assumptions can be enforced incredibly quickly if there is nothing there to block and correct them.

Before this section ends, we want to reiterate that we, in no shape or form, were able to cover every important article that the Evanstonian published about race that was worthy of critique. Due to space constraints, we were not even able to address every notable article within the publications we discussed. We were largely guided by the wonderful alumni who took the time to speak with us, and we were also constrained by COVID-19. Only one person could go into the school at certain times to find relevant pieces, and many copies of certain issues could not be found. We in no way addressed everything that was worthy of being addressed and know that there is still much room for discussion surrounding the Evanstonian’s history.

Tom Brueggemann • Feb 22, 2021 at 7:15 pm

Just discovered this website – wondered how the Evanstonian had evolved.

I was editor in chief for 1969-70 year. This was right in the middle of Vietnam, student rebellion, lots of liberalization at ETHS. Not sure if anyone around knows, but this was the year we had an issue banned from distribution because of content reasons (long story, not the biggest foul ever, but a big enough deal that we had coverage in all then four Chicago daily newspapers, including front page of two of them.

My class’ 50th anniversary reunion has been delayed, but it has allowed more of my fellow staff members (and I was surrounded by amazing people) to reconnect. It’s hard to do this without some reflection. The hardest one to deal with is that we had no Black students on the paper. Not one in junior J-English class.

What is more shameful is that it didn’t seem so bad at the time. We were mostly to all typical late 1960s Evanston anti-war liberals. We were pro-Civil Rights. But somehow we never thought to raise this or make steps to improve.

This was so much like ETHS at the time (have no idea about now). With the tracking system, except for PE, health, maybe some electives, I had very few classes with Black students in them. I got a fine education for sure. But it was lacking something critical for me, and I suspect far more damaging for those who didn’t have the same opportunities.

It was good to see that in later years those who followed recognized the problems and started to deal with them.