Opinion | ‘NIMBY’ in Evanston

Exploring residents’ attempts to dismantle the work of the Margarita Inn

March 15, 2023

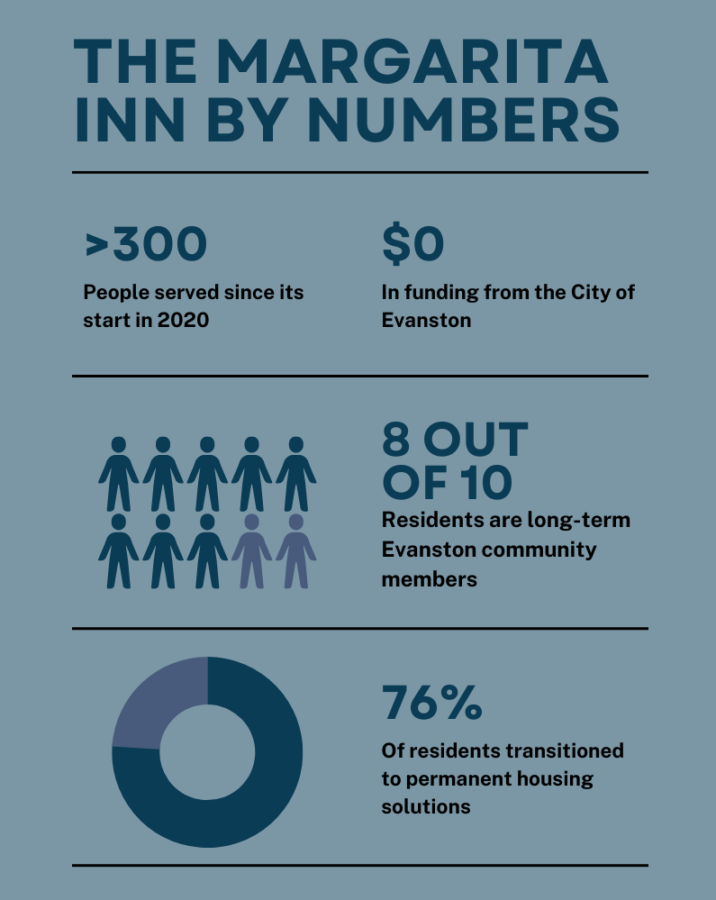

Nestled in the heart of downtown Evanston, near popular landmarks such as Five & Dime and Bennison’s Bakery, lies the Margarita Inn: a long-term homeless shelter emblematic of everything this city prides itself on. Unlike Evanston’s overnight emergency shelters, the Inn allows residents to stay there during the day, keeping them off the streets and providing opportunities to find permanent housing. Inside, the Inn retains much of its charm as a former European-inspired boutique hotel; the walls are still lined with wood paneling, with each room highlighting its signature midnight blue color. Since 2020, more than 300 people, 80 percent of whom are Evanston residents, have found a temporary home in the Margarita Inn.

In a city as supposedly welcoming and forward-thinking as Evanston, one would expect that such a revolutionary solution to homelessness would be welcomed and even celebrated by its residents. Unfortunately, a movement that can only be described as ‘NIMBY,’ or ‘Not in My Backyard’ has made its way into the pillars of Evanston, harming the Inn’s prospects of permanently taking over the space.

As Homeless Hub explains, “NIMBY, an acronym for ‘Not In My Backyard,’ describes the phenomenon in which residents of a neighborhood designate a new development (e.g. shelter, affordable housing, group home) or change in occupancy of an existing development as inappropriate or unwanted for their local area. The opposition to affordable, supportive or transitional housing is usually based on the assumed characteristics of the population that will be living in the development. Common arguments are that there will be increases in crime, litter, thefts, violence and that property taxes will decrease. The benefits for the residents of the development are often ignored.”

With regards to the Margarita Inn, residents have embodied this ‘NIMBY’ mindset in their attempts to dismantle Connections for the Homeless’ goal to renew its special use permit—a necessity to continue its operations in the space. Since February of 2022, the process has been widely publicized, as residents bombard City Council meetings to voice unfounded complaints over things such as crime rates—all of which has been disproven over and over again by Connections for the Homeless. Even after businesses, city residents, Margarita Inn residents and Connections for the Homeless collaborated together to create their Good Neighbor Agreement, allowing for oversight of the Inn’s work with a revocable permit, people continue to undermine its objectives.

“I wish I could explain the pushback surrounding the Margarita. The arguments against the Margarita, including those regarding crime [and] police activity have been disproved. The crime rate in the neighborhood has been relatively stable over the years,” Connections for the Homeless Chief Development Officer Nia Tavoularis explains. “Connections has a growing relationship with the Evanston police that has improved communications and data sharing.”

When considering the few events at the Margarita Inn that did require police presence, of which were likely linked to underlying physical and mental illnesses, these rare occurrences still do not justify ceasing the Inn’s operations. They do not justify leaving vulnerable people out on the streets, still struggling from the mental health problems that, oftentimes, were what led to their state of homelessness in the first place. Instead, this serves as justification that the city needs to do more in addition to allowing a non-profit to support its homeless population at no cost. Rehabilitation programs need to go hand-in-hand with the work from the Margarita Inn, and that responsibility shouldn’t fall solely to Connections for the Homeless: it should go to the city.

In fact, the Margarita Inn has already begun to provide its residents with some of these support services.

“Participants at the Margarita get their own room, can come and go as they please and receive rich support services to help, including on-site physical and mental health care services, case management support, and most importantly help finding a permanent housing solution outside of the Margarita,” Tavoularis says. “The average stay for a Margarita resident is around eight months, and over a nearly three-year period, March 2020 to Jan. 2023, our success rate in finding permanent housing solutions for Margarita residents is 76 percent, nearly twice the 40 percent national rate average.”

76 percent. The Margarita Inn has found 76 percent of people that would otherwise be out on the streets with permanent housing. With all the complaints spurring from these same residents surrounding panhandling in Evanston, one would think that this success rate alone would be enough to convince them of its importance. However, as crowds continue to flood Land Use Commission and City Council meetings to complain, this, unfortunately, is not the case.

“There was a moment in the spring of 2020 when homelessness in Evanston was ended,” Connections for the Homeless CEO Betsy Bogg noted in her remarks to the Land Use Commission. “People were off the streets, they weren’t sleeping on the train or in vestibules, they were safe, they were sheltered. This new model worked.”

Ultimately, Evanstonians’ desire to terminate Margarita’s special use permit does nothing but expose the sad truth: Evanston just isn’t that progressive. Residents can display Black Lives Matter placards in their front yards and throw money at various charities to feel good about themselves, but when real, sustainable change requires a level of interference into their lives, far too many people turn their backs on the cause. Fundamentally, Evanstonians are only liberal when it’s convenient for them—when they can brag to their friends about living in the first city to offer reparations or when they can reminisce about that time they volunteered at a soup kitchen three years ago, but not when a homeless shelter, that could permanently combat homelessness in Evanston, needs their support.

Now, coming out of COVID-19, as affordable housing units are being traded in every day for gigantic, luxury apartments, the work of the Margarita Inn is especially important to ensure sustainable living solutions. Currently, according to 2021 Census data, 83 percent of Evanston households making below $50,000 per year are paying more than 30 percent of their salary on rent—a status that puts them in a financially precarious position. In just one year, the average rent of a studio apartment has increased 73 percent, the average rent of a two-bedroom has increased 30 percent, while the median household income only increased seven percent. Evanston is undergoing gentrification at a rapid rate.

It’s the work of organizations like Connections of the Homeless and its Margarita Inn that have been able to combat this gentrification by supporting people with rent subsidies and housing solutions.

“During quarantine, I lived in Skokie with my aunt, but eventually went homeless. I stayed in hotels and Airbnbs during that time that my mother had to pay for on her own,” junior Malory Frouin notes. “We didn’t really receive any support, besides food stamps. After a year, Connections for the Homeless gave me the apartment I live in now at a reduced price.”

Thus, it’s this work, supporting real people like Frouin, that self-proclaimed liberals are trying to shut down.