Editorial | In addressing safety, ETHS must center experience of marginalized students

December 16, 2022

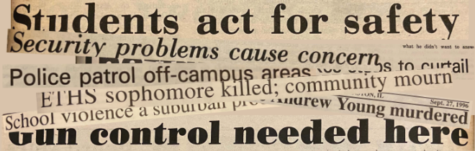

When speaking about safety, we tend to hear the word “after.” “After Columbine,” “After September 11th,” “After Sandy Hook,” etc. We use these scarring events as markers to gauge dramatic shifts. We focus on the post-event atmosphere, but never the before. When the ETHS and broader Evanston community discusses safety, many of us fall back into this language: “After Highland Park,” “After the gas station shooting” and “After December 16th.” But the reality is, there are students that have felt unsafe at ETHS before all of these events, and many of those students are from marginalized communities.

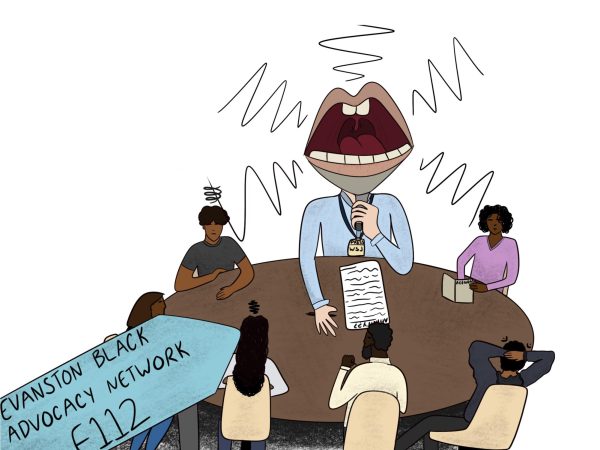

Conversations about safety at ETHS are happening between students, parents, teachers and administrators, and The Evanstonian has a commitment to the Evanston community to thoroughly and intentionally address this topic. Too often, these discussions are solely driven by measures to make school physically protected from violence, and in the process, the conversation becomes dominated by fear, surveillance and control. That said, ETHS will not be a truly safe place until marginalized students are free from excessive policing and discipline within their educational experience.

This begins with acknowledgement of past and present injustice, conscious community building and deliberate policies to change the current climate surrounding safety at ETHS. Recently, the administration has instilled policies that have contributed to a culture of fear. These policies include an uptick in surveillance, an increased focus on policing the hallways and ‘in school truants’ as well as a harsher procedure surrounding disciplinary infractions such as being tardy or having a phone in class. ETHS students should be able to follow the rules, because they trust the people who made them, rather than fear those in charge.

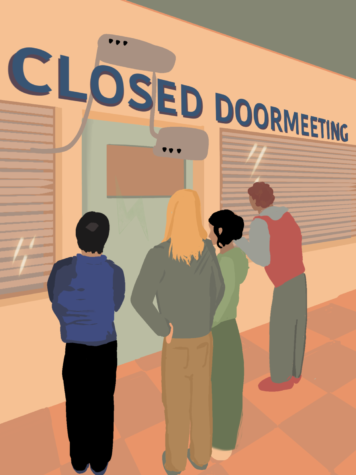

The first step in building trust is clear communication and transparency. The school needs to increase its education surrounding expectations for students and what will follow in the event that these expectations are compromised. This includes advertising the importance of the pilot and carefully breaking down the key elements of the pilot in digestible formats for students, potentially through teachers, announcements and/or emails. In addition, we also urge the administration to carefully reconsider what offenses are eligible for expulsion and how that information is organized in the Pilot. For example, on page 38 of the Pilot, pepper spray is listed as a prohibited item, which is not noted as eligible for expulsion. However, on page 41, pepper spray is categorized under weapons, which can warrant expulsion for up to two calendar years. This conflicting information creates a lack of clarity for students reading the handbook. In our investigation of this topic, we interviewed two separate students who had no previous disciplinary violations and complied with the administration after being found with pepper spray on their person, yet they were given a recommendation for expulsion. This lack of clarity poses the question: when does ETHS choose expulsion and why? Statistics show that the vast majority of suspensions and expulsions are administered to students of color, which we explore later in this issue. In order to bridge this gap, the administration must take measures to prevent students of color from being eligible for expulsion and revise the severity of punishments that students receive based on their infraction.

To be clear, The Evanstonian does not condone any violation of the school’s code of conduct. That said, at a school full of teenagers, mistakes are bound to happen in addition to violations with intent, and there needs to be a careful and equitable procedure in place to appropriately manage these occurrences. When a student is convicted of a school offense, the administration must practice full transparency throughout every stage of the disciplinary process. Many students do not know their options and rights when it comes to this corrective procedure, and it is the administration’s responsibility to fully and honestly reveal this information to students. Misconceptions about Pilot policy and the appeal process drive students to accept consequences that they do not believe align with their behavior. Students at ETHS are being sent to attend school at a different location, because when presented with this option in lieu of further consequence, they are coerced to believe that if they do not accept this deal, they will be expelled. These students do not know who to talk to and what support they have available to them, and therefore, they are disadvantaged throughout this process.

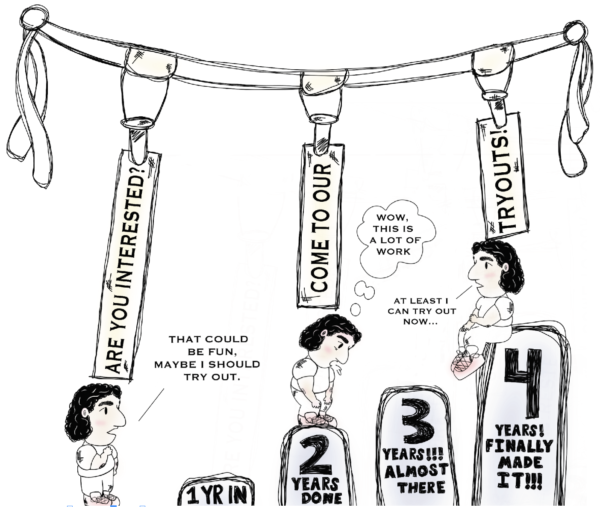

Broadly, because of these aforementioned factors, our current discipline system does not work. This process should be student-centered and equitable, but instead, it is often impersonal and discriminatory. A possible solution to this is a peer jury, with which some districts across the country report having found success, or the school could consider any of the plethora of restorative justice practices that are being implemented in other places. This would allow for passionate members of the ETHS community to devote the due time to ensure that every student is tended to with conscientious and student-centered care. In 2016, when ETHS made the leap of changing the school dress code, the administration replicated the recommended dress code by the Oregon National Organization for Women in order to create an effective new model. In changing the current discipline policy, we expect the administration to, once again, use procedural models that are built on the foundation of equity to form a thoughtful and effective revised structure. In addition, when a student endures a disciplinary consequence that excludes them from attending school at ETHS, the administration must provide more support to help them return to ETHS classrooms.

Following a return from an expulsion or alternative schooling program, students are often left feeling isolated and sometimes unsupported. We advise the administration to establish a reintegration program to confirm that a student is in a healthy state of mind and feels prepared to return to ETHS. Part of this may include initiating a meeting between the student and a school mental health professional to equip the student with the proper resources to return to school. In a school with over 3,600 students, the administration must go the extra mile to protect students and their social-emotional wellbeing with individualized support.

We understand that physical safety is a priority. The Evanstonian does not attempt to conceal or underplay the suffering that gun violence has infected our nation with, nor the right to a physically safe school. We acknowledge that safety in high schools is a national concern, and the community has a right to emotionally and assertively invest in it. Physical safety must be a priority, but it cannot be prioritized over mental and emotional safety of students. They must be co-existing forces, and that is the balance that we ask the administration to conscientiously reflect upon and integrate into ETHS procedure.

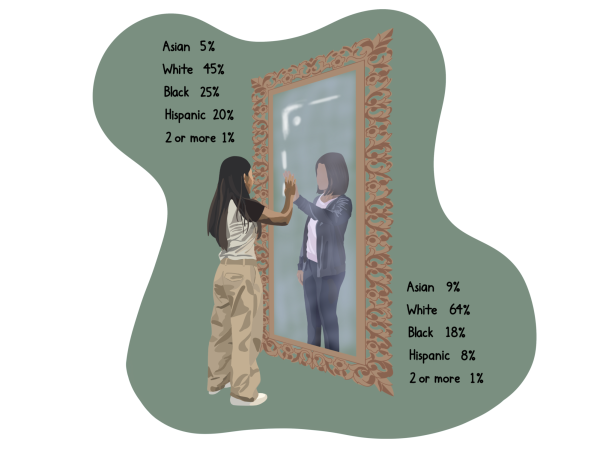

We would like to acknowledge our position when analyzing this topic, which has historically harmed students of color at a disproportionate rate in comparison to their white counterparts. As a primarily white editorial board and publication, we acknowledge that white students have not been historically disenfranchised by the policies and procedures we discuss in this issue, and as a result, our personal experiences affect our ability to accurately report on these stories and see our identities reflected in these pieces.

We recognize that the safety concerns we investigate throughout this issue pertain to high schools across the nation, and we are privileged that we have the resources at ETHS to address this topic in a meaningful manner. However, at a school and a community that has been nationally recognized as leaders for change, it is shameful that despite having the awareness and the capability to create policies that reinforce empathy, we still find ourselves producing policies that dehumanize marginalized students. ETHS must do better.

As you engage with this issue, it is vital that the conversation does not end here. The Evanstonian recognizes that safety in high schools is a nuanced topic, and we have not at all addressed all aspects of this issue. The community and the administration must commit to tackle this historically significant topic through ongoing reflection, dialogue and action. We have a long way to go to make school a safe space, both physically and emotionally for all students, but we hope that our December issue of The Evanstonian serves as a piece of this continuum that moves us towards justice.