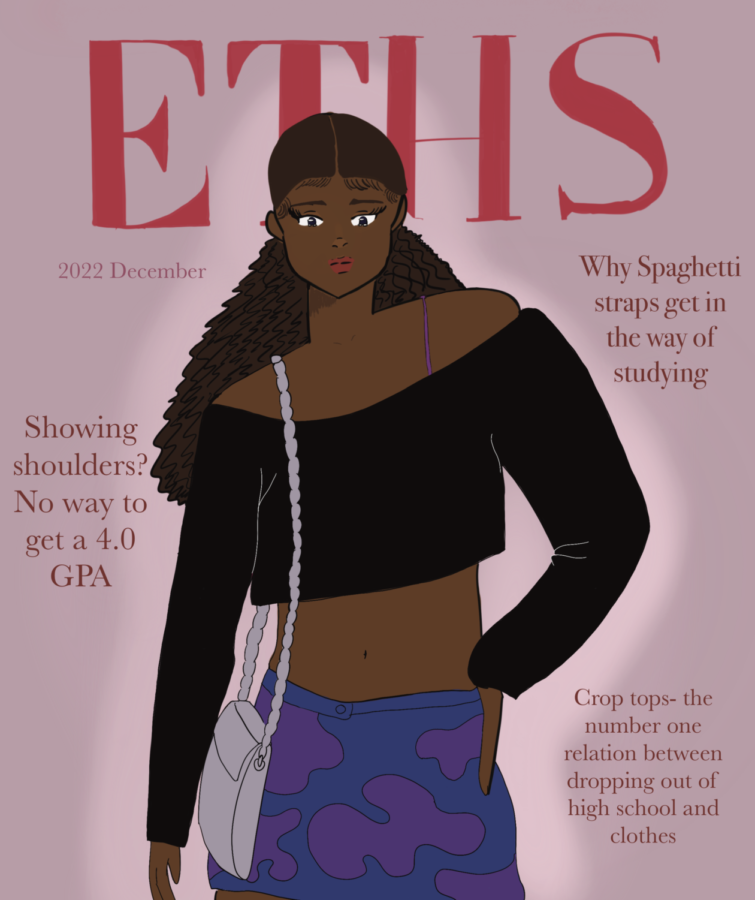

Decoded: The student who pushed ETHS to remove its sexist dress code

December 16, 2022

As the crisp air swept past then-junior Marjie Erickson when she left her house to head to school in 2015, her mind wandered to all the excitement for the play she would take part in at school that day. On this very occasion, Erickson and others involved in theater made the executive decision to dress up. With her favorite dark red tights, a gray, long-sleeve wool dress and little boots, Erickson was ready for yet another day of school. Little did she know that hours later, as she made her way to gym class, she would be promptly stopped and dress coded. This event stemmed anger and a need for change regarding the policy within Erickson, forever changing ETHS in the years to come.

Before the 2017-18 school year, the ETHS dress code focused on restricting clothes that were seen as “distracting” or “too much skin” and “revealing.” Clothing such as short skirts, all pants not past fingertip length, spaghetti-strapped tops, low-backed tops and anything showing cleavage would go against school policy if worn at the time.

Back when Marcus Campbell, our new superintendent, served as the principal, he agreed with many others on the need for a revised dress code.

“The language in the Student Handbook at that time was just so antiquated and outdated, it was a female identified dress code, because all of the language was about what female girls wear, and nothing to do with boys,” Campbell says.

Humanities and psychology teacher Matt Walsh recalls how the restrictions within the dress code were directed towards clothing that most females at the school would wear and not men.

“It was almost all about what females wore; how long a skirt had to be, spaghetti straps on shoulders, and a bunch of stuff about covering bodies. There may have been something about people pulling up their pants, but mostly, it was about patrolling female bodies and not male bodies,” Walsh states.

So, in the fall of 2015 on that fateful day when Erickson would end up dress-coded, she found the incident to be representative of the larger problem with the school’s dress code.

“I’m a bigger girl. I developed early, and I would be dress coded for wearing the same thing as a girl with a more athletic [build],” Erickson voices. “[This] actually happened my junior year. I was dress coded, and then two days later, my friend in my history class was wearing the exact same thing as me, except that I wore tights under and she hadn’t, and I got dress coded and she did not.”

After a student is dress coded, there are a few options to consider. No matter what, you have to change out of or fix the piece of clothing that you were coded for, some even would need to wear their gym uniform. If none of these options suited them, the only other choice was something known as dean’s wear, which physically said ‘Dean’s Wear’ on it.

“I have multiple friends who I can think of off the top of my head [that] would show up [for] the second half of the day wearing these big sweatpants; I don’t know where they got them but it was the ‘dean’s wear’, and it was a big mark of shame. It was about shaming young women for living and breathing,” Erickson explains.

Having graduated the year before the dress code policy was changed, Erickson is now living in Dubai but still to this day recalls the unfairness and fury that was brought about by the dress code when she was a student. Her main issue with the policy revolved around its enforcement, and its sexualization of young women as if they were a distraction and problem that needed to be fixed.

“The big problem was that Black girls were getting dress-coded left and right. Athletic-type white girls were not getting bothered at all in the same way. It was super gendered and very much ‘you have to cover up because you’re distracting’ and ‘your body is wrong,’” Erickson voices. “My whole thing was, ‘Aren’t we just kids trying to get an education?’”

Knowing these policies needed to be changed and were implemented for all the wrong reasons, Erickson dedicated an enormous amount of her time over the course of her junior and senior years to taking action on this issue.

“I was doing some surveys when I wanted to change the dress code senior year. And it was found that way, way, way more women of color, especially girls who developed early [were being targeted],” Erickson shares.

Within the surveys Erickson conducted, it was found that, according to Erickson, “48.9 percent of the 151 girls that surveyed about being dress coded self-identify as having a ‘thick’ body type, or with a larger or curvier body type than average,” and when girls are taken out of class or stopped in the hallways, “3,570 minutes of class were missed in total, meaning an average of 43 minutes, an entire period, missed.” This further proved to Erickson and many other students at the time that the disruption of learning isn’t being caused by those neglecting to follow the dress code but instead being made by staff members who take class time away from students who happened to be dressed in clothes that don’t follow the policy.

In addition to the surveys administered, Erickson also led a silent sit-in protest in the main lobby of ETHS during her senior year. It was held during the third period on a Friday and lasted about 25 minutes, according to Erickson. Just about 200 students attended; they sat silently protesting, as Erickson read a statement on the flaws within the policy, with hopes of getting the administration to take action. Everyone participating would not leave and return to class until someone with the power to change the policy agreed to speak with them. While Erickson awaited the administration’s response, she tried to get her story out through the Evanstonian.

Following the student-led protest, Evanstonian writer Rachel Krumholz wrote an article based on the event and more specifically, Erickson’s leadership and work towards the issue. She summarized the several points Erickson spoke on, including her push for others to not stay quiet. She highlighted the importance of speaking up, whether it’s to administration, through organizing a protest or just having the difficult conversations that catalyze change.

Eight days after Krumholz’s article was published, the Evanstonian editorial board published another article that directly opposed the one before it, aimed at Erickson. The editorial “Organize meetings not protests” aimed to spread the message that rather than having protests at school, a better way to handle any situation is by organizing a meeting or speaking to the student representative about the issue at hand.

“No more random protests. No more disorganized complaints. We all have a voice; we just have to use the correct outlet,” the editorial board wrote.

After Erickson saw this article, and how it seemed to be directed at her recent protest, she decided to have a conversation with Rodney Lowe, the advisor of the Evanstonian at the time.

“Lowe said, ‘Oh, you can publish a response. I’ll publish your response.’ So, I wrote up a response about how the article was not [truthful] and in the interview [with Rachel, I discussed how I] went through the proper channels, how I met with the deans, how I met with the assistant principal, all this stuff,” Erickson clarified.

Despite Lowe having been clear about his trust in his journalists throughout the conversation, he did allow for a response from Erickson to be published in the Evanstonian. Erickson gave her retort to the Evanstonian to publish with clear instruction of only mechanical edits made to it. However, her request was not respected.

“They published it, referencing the wrong article. So I had written, in response to the editor’s opinion piece from last week, and they edited it to say that it was about something else,” Erickson states.

Despite the criticism and roadblocks she faced through the school’s media outlet, she found success with getting through to the administration, and eventually, Campbell agreed to speak with Erickson.

“I talked to Campbell and learned that the only way to change the dress code was through the school board,” Erickson explains. “For the next couple of months, [I went] to the disciplinary committee meetings. There are four every year, and I went to three of them.”

This committee makes recommendations for changes to the handbook, which included the dress code, so by attending these meetings, Erickson was able to voice her opinion and listen in on important conversations. However, many adults told her that no change was going to be made and that all her work was pointless.

“How dare they? We’re minors without rights. We don’t have anything. We can’t do anything for ourselves. And then we go to school, and we’re sexualized for living and existing with bodies, and it just pissed me off,” Erickson exclaims.

Despite being a bit discouraged, Erickson decided she needed to take things into her own hands. She found a dress code from the Oregon Public Schools that was completely non-gendered and rather than what couldn’t be shown, it focused on what needed to be covered.

“I brought that dress code [to the disciplinary committee] and said, ‘Look, here’s a great model. We can model it after it. We can even just adopt the exact same one if we wanted to. Either way.’ Around college admissions time, probably in April, I had pretty much given up, because everyone was telling me that it wasn’t happening,” Erickson says. “In July, when they put out the new handbook, one of my friends emailed me and said, ‘Oh my God, you have to look at the new handbook. They did it. They actually changed the dress code.’”

Despite her fury, everything had worked out in her favor as well as all her peers and students for generations to come attending ETHS.

The modifications to the dress code, beginning in the 2017-2018 school year, allowed all sorts of clothing with restrictions only on violent or inappropriate language and images on clothes. The policy is completely different from how it once was, largely due to the help of Erickson and the many other students that spoke up and took part in making a change. Instead of the new policy being highly gendered, it now focuses on what needs to be covered up.

Teresa Houston, a teacher during the old dress code policy, now teaches fashion design. She shares her opinion on what she’s noticed among ETHS ever since the new dress code was implemented in 2017.

“Students have complete freedom to wear whatever they feel most comfortable in. And we’ve moved away from that narrative of ‘girls are distracting’. I have students show up in all sorts of things. And I think it’s good, because obviously, I advocate for fashion being part of our identity. So, students being able to show up feeling comfortable is really important.”

In agreement with Houston, Walsh sees it as a shift of power and control in favor of students.

“Everything’s calmer about it now and [I] should not have to be in charge of what the student wears. It just makes it so we don’t have to worry about it and [the students] get to be in charge of themselves.”