Unpacking the complexities of racial identity

November 8, 2019

It is important for me to share my experiences with you because I am not the only student who feels this way. Whether it is gender identity, sexuality or race identification, many students are struggling to understand how they identify within these many intersections. Being a biracial, black-white mixed person has impacted my life, whether it had to do with school or my social groups. Growing up, I attended predominantly white, upper-class schools, which affected the way I identified at a young age. I went to Orrington Elementary, an upper-class North Shore school, where according to Illinois Report Card, only around 16 percent of students are low income.Throughout my time there, I tried my hardest to identify as someone who was a part of that upper-class community. Even though I lived in the 5th ward, I didn’t have as much financial stability as other families, and I identified as a person of color, I tried my hardest to downplay my differences.

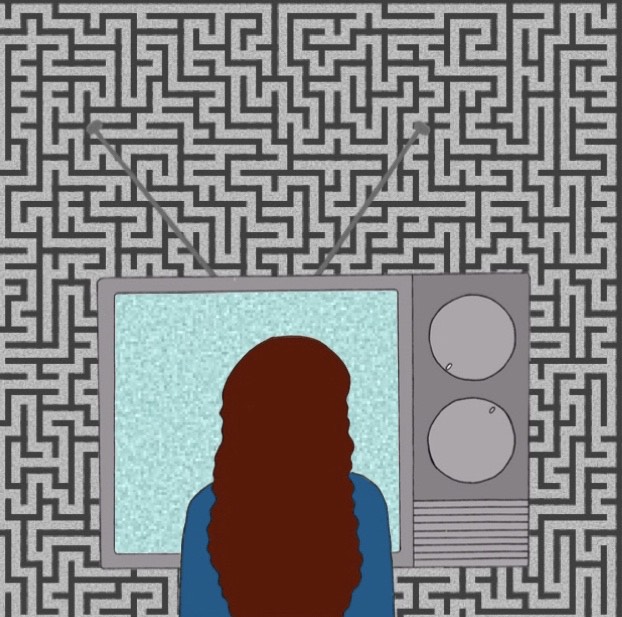

When playing with Barbies outside of school, I refused to use the black one. While my black friends liked black characters, I liked the white ones better. In the 1940’s, Doctor Kenneth and Mamie Clark conducted the Doll Test study and found white and black kids tended to prefer a white doll over a black doll. Although I didn’t know about the study at the time, this study was true for me; I myself was a child who preferred the lighter-toned dolls. A study conducted by the University of Illinois at Champaign on the portrayal of black people in the media showed that blacks are misrepresented in the media; growing up with social media and my phone affected how I saw myself. I saw white women on social media platforms and spent most of my time around people, both at school and out-of-school, who looked like these women that it affected my self-perception.

As a student, my life at Orrington was also shaped by the history we learned in class. Race was prevalent in our classroom but not present in our curriculum. Students only learned about white history, so it was hard for us to talk about race because the history of black people was never taught. Even today, I haven’t experienced curriculum that focuses on black people in my core classes. At Orrington, I didn’t have any black identifying teachers; in the school building, there was a lack of representation of black teachers who I could identify with. Not learning the history of one side of myself was another factor that made it hard for me to identify with my black side.

Even though we never explicitly discussed race in my elementary school classes, Haven Middle School seemed to expect students to understand the complex idea of race. The lack of representation with teachers was still present. At this point, I was mainly friends with people of color. I was still noticing that both black and white friends and peers would say I dressed white, or I acted white. Not only was middle school problematic due to the fact that friend groups were dissolving, but racial differences among social groups were very much noticeable. The white kids sat on one side of the cafeteria and the black kids sat on the other side. This added to the confusion of my identity because I was able to choose either race but by doing so, I would be putting half of my race aside, which made me feel as though I was erasing part of my history. Being biracial, I have always felt like the odd one out for having conflicting experiences and feelings about my race. I now understand how my formative experiences with schooling — experiencing a lack of explicit discussion about the history of black people and the lack of representation of black teachers in my younger school years — played in my internal conflict.

Once it was time to register for high school, I didn’t know that I was able to choose more than one race, so then I thought I had to choose one of my two races. It took me no time to decide what I wanted to pick — white — because I thought I could benefit from privilege. But once I arrived at the high school, I noticed that my black friends would be invited to community events that only black people could attend, such as the celebration of black honor roll students or student summit for black females my freshman year, which often made me feel excluded because I wanted to be a part of those spaces.

While initially I felt excluded, now at ETHS I have felt widely more accepted than I have in elementary and middle school. I am able to identify how I want because students are more open to accepting differences. During my first two years at the school, I felt somewhat unwelcomed to the black community because there were quite a few events that I wasn’t invited to; in the school system, my race was white. In my sophomore year, I was eventually able to change my race to black in the system. Often, peers of all races tell me they don’t see me as black, or they don’t see me as white, and that adds to my identity confusion. My problem with identifying as biracial is that it can mean other mixed-race identities, and I often feel that saying that will cause confusion between which races I am mixed with. Having access to black representation and an accepting community makes it easier to identify how I wanted to.

Most of my life, I feel as though I was identifying as white due to my upbringing being around many white identifying people and lack of representation of black and biracial people in the media and school. At this point in my life, I still have a feeling of uneasiness with my racial identity because of how others perceive me. Although this unease exists, it is my own identity. I still do not have a clear understanding of how I feel about my race, but I am more open to identifying as biracial or mixed when people ask because I have been able to learn more about my race as a whole. For other people who are struggling with their identity, I encourage you to tell people how you identify. Once you begin to unpack your own thoughts on your identity, you can find acceptance by others who will take you as you are.