Intentionality of language is everything: an examination of the N-word

November 8, 2019

On October 15, actress Gina Rodriguez found herself at the epicenter of public backlash for a video posted, and then quickly deleted, from her Instagram. While jamming out to the Fugees, Rodriguez rapped the N-word on a live stream with hundreds of viewers. As a part of the Latinx community, Rodriguez’s choice raised questions as to who’s entitled to say the N-word and in what context. With the popularization of the N-word and its usage in general, its long and complex past in regards to black history is not too far behind. But as time progressed, the word’s significance changed. Today, its usage is well-known and normalized in some social contexts. It’s not uncommon that the word litters a rap verse or is flung around in conversation, but in other contexts, such as educational establishments, its meaning shifts completely.

Time and time again, non-black persons use their proximity to blackness as justification for saying the N-word, disregarding their racial positioning. They reference music, movies and other aspects of social interaction almost as if to excuse the fact that their family history does not coincide with the victims of the N-word. As a black woman, I have a complex understanding of who should use the word and when, but in the way that history has played out, not having a personal connection to its history is reason enough to leave it out of your vocabulary altogether.

“The N-word is very difficult to avoid in history, especially American history,” says Samoane Jones, Chair of the English and Reading Department. “It’s probably the heaviest word in the English language.”

Derived from the Latin word “niger” meaning black, the word has been at the forefront of racism towards black people for hundreds of years. Rooted in horrid violence, degradation and ridicule, its negative impacts are well documented in America’s racist history.

“It makes me disgusted that there was so much hatred towards black people and that they were called the N-word in a way that was meant purely to crucify them,” says senior Sophia Brown.

Growing up, learning about Black history brought me as much pain as it did joy. The pride I feel when learning of the triumphs of my community, despite the ruthless adversity, is unparalleled. Yet, I still cried when watching 12 Years a Slave in my English class, (the censored version I might add) feeling myself bubble with anger every time Solomon’s slave owner spewed the N-word in his face or whipped the skin off of Patsey’s back.

“It means something different to different groups of people. It’s generational, it’s cultural, and it’s cultural within the black community. I don’t think we can divorce the word from its origin,” says Jones.

Besides what’s documented, I will never be sure as to how exactly the N-word was used, but as it has evolved, I find the evolution of its meaning both fascinating and angering.

“The word is used in the black community to refer to each other, taken from a negative connotation to a reclaiming of the word instead,” says junior Naiyah Bryant. “It should only be used by black people to other black people because it’s current positive connotation. Anyone else who’s not black and saying it would alter it back to a negative state.”

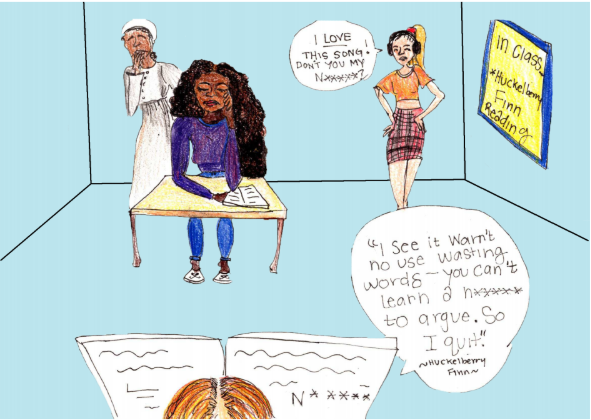

At Evanston, students have reflected on how their teachers’ efforts to work around the word affects their experience in the classroom.

“My [English] teacher decided to use the phrase ‘N-word’ instead of the actual word. I think it’s respectful to choose not to say given your identity if you’re not black,” says Bryant. “I think that if a teacher were to say it, regardless of their race, it would give kids the feeling that they can say it too.”

On the other hand, some students feel like hindering the word’s utilization alters its definition in literature.

“There have been instances in my English class where the N-word is in the text, and the teacher will give a code word for it or skip over it,” emphasizes Brown. “I think assigning an alternate word takes away from its purpose.”

As a student who identifies as a black woman, I struggle to identify the parameters in which the N-words should be used, especially in an educational context. Currently, there is no specific language in the current faculty handbook or the The Pilot that addresses teacher or student use of the word. I do feel that even in the most uncomfortable contexts, I believe that young people should be knowledgeable of how the N-word appears in literature. The works of Frederick Douglass and Solomon Northup offer a necessary perspective on American society, and their use of the N-word in their writing offers students the opportunity to understand, to some extent, the lived experiences of the people who preceded them.

In response to Rodriguez’s actions, I feel accountable to the same ethical dilemma. My relationship with this word is still dynamic. As I reflect on my own language, read more about the history of my Haitian ancestors and engage in more conversations about the word’s usage, I understand that my relationship to language is still in a state of flux. The progression of time does not excuse the truth: that intentionality of language is everything.