A lesson before falling through the cracks

March 22, 2019

The bookshelf tipped at your feet, but as the spine of Corduroy shattered to fragments, as the pages of Knuffle Bunny fell to shreds and as the wails of Goodnight Moon rotted to nothing, your teacher saw the desire for destruction gleaming in your glassy eyes, that were begging to spill onto your reddening cheeks.

She held your wrist tightly, dragging your body across the room, feet dancing along the carpet, arms flailing in the air, while you cried and clawed for any last clamor you could hold onto, even as you felt it melting away softly in your palms.

She may have seen that desire for destruction gleaming in your eyes, but if she only saw you. If only she saw you beyond just another brown face that she was tasked with taming. If only she saw you beyond just another brown face doomed to chewed up and swallowed by the system. If only she saw you beyond just another brown face that desire destruction.

Because your desire for destruction was a desire for direction, a reach, a hold, a grasp onto anyone or anything who would stop you from falling through the cracks.

From as early as I can remember, I pranced along the cracks. Every time my black Mary Jane-clad feet landed on the ground, a rumble of destruction followed. From knocking over block towers as my classmates wept to shrieking in class just to see who would cover their ears, I was, by all standards, a disruption.

For two years, I wreaked havoc on my Lincoln Elementary School kindergarten and first grade classes, which, coupled with the fact that I was reading levels behind where I should have been, centered me at the object of teacher resentment early on.

And as the resentment grew, so did my desire for destruction, which culminated in anger. An anger that surged from my mother being called “a monkey” and anger that landed me in the principal’s office with a suspension.

I could feel my body slipping through the cracks in that moment, even with my six-year-old sentience. But, as I felt my body start to fall, I saw a hand—my mother’s hand. And as she lifted my sinking body, she moved on to defending me, protecting me, washing away my principal’s words, which were painted with hues of scorn and enmity.

From then on, I no longer possessed the desire for destruction that once filled every fiber of my being. Where school had become a place of animosity, it then became a place of opportunity, all because I had one hand to hold me before falling. But, what is to be said of those who are left to slip?

For many of my peers, the grip of the American public school system loosens, and they fall. They plummet. They sink. And the ones that sink, the brigade of the “bad kids,” who slowly start to clad themselves in resentment of their teachers, their peers and their beloved education system that is supposed to protect them, they sink below.

Below, in the breaches of society, lay the former “bad kids,” into the forgotten crannies, the nothingness of neglect, where the dust coats the walls, floors and corners. The smiles of the once-emanant fade into grey. The yearnings of the once-eager disintegrate into powder. The hope of the once-innocent fractures into cracks.

We let them fall through the cracks because, somehow, the cries of the “bad kids” don’t ring through the air like those of the “good kids,” and we do not only let them fall, but we also watch dullily as they do, using their anguish as a lullaby as we drift off into a bed of ignorance and negligence, repeating to ourselves quietly, “We’ve done all that we could to help them,” all so we can sleep through the night.

In truth, we’ve done nothing. Where we could have fostered growth, we , instead, fostered binaries, dehumanizing binaries between the “bad kids,” the inhabitants of the corner, the referral recipients, the eternally-abhorred and the “good kids,” the inhabitants of the front row, the compliment-clad, the eternally-adored.

From early on, mostly within the first three years of your public education, which in many ways are the most formative, you are sorted into one of the binaries, unbeknownst that if you do not fit the mold for what it means to be “good,” a life of being “bad” and a destiny of falling forever. Thus, a gap of resentment, one fueled primarily by the teacher’s affection and attention, persists, as the “good kids” are showered in accolades while the “bad kids” are left to be doted on upon with animosity and hatred.

Resentment takes on many forms, and while it mostly extends out from the teachers, it uncontrollably filters into the young, impressionable minds of the “good kids,” who take the teacher’s words and actions as a gospel to their adorant nature.

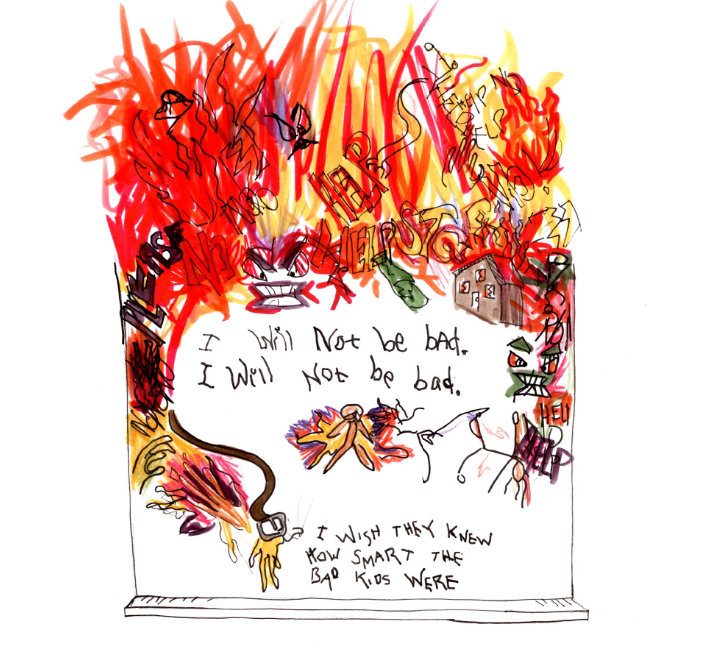

In the conversation of resentment, the age-old tradition of humiliation rears its ugly head. And, even as this widespread humiliation, which is also referred to as corporal punishment, has been deemed akin to an Eigth Amendment violation, its complete end in American public schools would be delusionally optimisic. From writing ‘I will not disobey.’ over a hundred times until your knuckles bleed to sitting in the corner, facing the wall with shame, modern-day corporal punishment serves its purpose—to further separate the “bad kids” by using resentmnet.

And the ostracization continues, leaving the “bad kids” alone with no one to reach out to, which leaves them no choice but the retaliate once again, with the same desire for destruction that brought them there in the first place. They cry and claw out in frustration from resentment and ostracization, expecting for their teacher to hold them, help them, and tell them that it will all be okay, only to have that teacher loosen their grip from their outstretched black or brown hand, and the cycle of destruction continues on.

As black and brown children fall through the cracks, the desire for destruction will dance along the glossiness of their eyes, twirling into their young minds fueled by hopelessness and loss of belonging, filling in tears of rage that drip down their face, onto their hand, their fist, their method of destruction, their method of crying out for help, their method of clawing for clamor. Clawing on, they go, scuffling for control, heart beating, gasping, sobbing, grasping, grasping for a hand that was never there to begin with.

As they fall, there is at least one thing that is certain—their teacher never loved them, their peers never loved them and their beloved American public school system never loved them. It resented them. It broke them. It let them fall.