Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

Letter from the Executive Editors | How NU, ETHS, Evanston can hold John Evans accountable, ensure Indigenous cultures can thrive

February 27, 2023

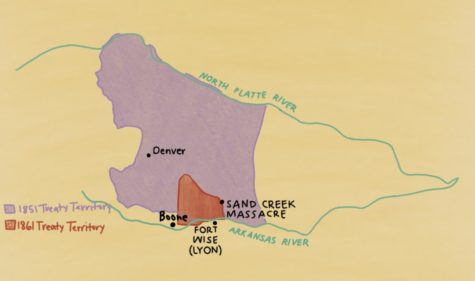

Right as the sun broke on November 29th, 1864, 700 volunteer soldiers entered sacred land in Fort Lyon, Colorado. Home to the Cheyenne and Arapaho, this vast prairie had become a community for over 700 Indigenous people. Yet the nation’s growing desire towards westernization would disrupt their way of life in an event known as the Sand Creek Massacre—our focus for this issue.

According to eyewitness reports, animosity began to arise between the Cheyenne and Arapaho and Colorado settlers after Colonel John Chivington dispatched the Third Colorado Regiment to investigate accusations that they had stolen cattle from neighboring white farmers on May 16th, 1864. When Cheyenne Chief Lean Bear rode out to meet the volunteer military group to make peace, the soldiers shot and killed him. In the months that followed, anxiety ran high between Colorado settlers, many of whom anticipated a full-out war in reaction to Lean Bears’ death. To ensure this didn’t happen, John Evans, the Territorial Governor of Colorado, founder of Northwestern University, and namesake of Evanston, authorized all Colorado citizens in mid-August to “kill and destroy all enemies of the county whether they may be found; all hostile Indians.” In September, Fort Lyon commander Major Edward Wyncoop arranged a meeting with Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle, six other Chyennne and Arapaho chiefs and John Evans in an attempt to preserve peace. Evans refused, and responded to the request by saying, “[B]ut what shall I do with the Third Colorado Regiment if I make peace? They have been raised to kill Indians, and they must kill Indians.” Then, upon daybreak on November, 29th, 1864, Colonel Chivington led men from the Regiment to Black Kettle’s camp and attacked without warning. Over 200 died, many of whom were women and children.

In the aftermath of the massacre, John Evans was forced to resign his position as territorial governor, but he received no formal punishment. In fact, Evans was welcomed back into Evanston and remained an active donor of Northwestern University until his death in 1897. Decades later, his legacy continues to be memorialized in Evanston, most notably on the steps of the John Evans Alumni Center, located between Sherman and Dodge.

As a publication, it is vital that we address historically significant topics relevant to Evanston. John Evans remains a presence in our streets, curriculum, awards and buildings; his influence follows us from the plains of Sand Creek to the shores of Lake Michigan. With such a large impact, Evans’ racist actions need to be recognized.

For too long, Evans’ involvement in the Sand Creek Massacre has been minimized to protect white people from experiencing guilt. In light of Evans’ contributions to creating infrastructure for Evanston, both ETHS and Northwestern often fall into the pattern of celebrating his legacy rather than acknowledging a difficult truth. It is essential that his racism is not overlooked by his material accomplishments. To do this, both institutions must critically reflect on their perpetuation of memorializing colonialism.

Ultimately, both institutions must build greater capacity to center Indigenous voices. In American culture, there is a predisposition to whiteness as the central narrative because of its accepted normativity, yet this reinforces forms of supremacy and power that produce and maintain inequality. If the Evanston community wishes to move forward in building a more just future, we must acknowledge the past so that history doesn’t repeat itself.

It is no lie that John Evans was a racist who did not view Indigenous people as human. Rather than respect the reservations of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, he believed that the land served a better purpose if it was owned by white people. There is documented proof that Evans made statements instructing Colorado citizens to kill and destroy “all hostile Indians.” Evans’ violent language highlights the intentional forging of differences between Native people and whites to justify heinous acts like Sand Creek. In his eyes, the Cheyenne and Arapaho were “enemies” blocking white farmers from moving west, therefore, they were a problem.

For ETHS and Northwestern University to commit to diversity, equity and inclusion, we need institutional transformation, and that begins by talking about John Evans’ culpability in a historic tragedy. With that said, we would like to provide a brief overview of our sections prior to your reading of them.

Our first section focuses on the early life of John Evans—his childhood, educational career and his founding of Northwestern University. Our second section examines Evans’ fight for political capital in Colorado through his position as territorial governor. Our third section describes the events leading up to the Sand Creek Massacre and what occurred the morning of. Our fourth section looks at the immediate response to the massacre in Colorado, the Midwest and New York, as well as the federal military trial that took place which indicted Evans. Our fifth section dissects the components and complexities of massacres in the United States from a sociological perspective. Our sixth section navigates both the Colorado and federal governments attempt at providing accountability for the massacre, including the 2013 federal class action lawsuit filed by descendants of Sand Creek Massacre victims. Our seventh section compares two reports, one published by Northwestern University and the other by the University of Denver, that examine John Evans’ financial and moral culpability in the Sand Creek Massacre. Lastly, our eighth and final section discusses Evanston’s contributions to Indigenous erasure from an educational, political and ethical standpoint.

As you read these stories, we hope that you feel inspired to discuss the impacts of colonization and use it to inform your actions and beliefs. The Evanstonian recognizes that the Sand Creek Massacre is a nuanced topic, and we have not addressed all aspects of this conversation. As a result, it is vital that the conversation doesn’t end here. The community must commit to tackle this historically significant topic through ongoing reflection, dialogue and action. To gain a more comprehensive understanding, we encourage you to engage with resources like podcasts, books, websites and movies.

Additionally, we would like to acknowledge our position when analyzing this topic. As a primarily white editorial board and publication, we acknowledge that our reporting cannot fully capture the multidimensionality of Sand Creek, and as a result, our personal experiences affect our ability to accurately report on these stories and see our identities reflected in these pieces. We have a long way to go to undo centuries of oppression, erasure and racism, but we hope these pages will foster meaningful dialogue towards sustained change.