Community is top priority for ETHS’ school resource officers

Attempting to buck criticism of police, school’s SROs build trust, serve as mentors

During sixth period on one Wednesday afternoon, I walk into the School Resource Officers’ (SRO) office on the first floor of the North wing. I am greeted by two people, broad smiles on their faces, welcoming me to take a seat. The chair is plush and comfortable. Two desks sit next to a coffee machine, with a bowl of leftover Halloween candy by the door. A large orange wall towers over the rest of the office, a stark contrast from the beige classrooms that ETHS students are used to. For the next twenty minutes, we discuss everything from school spirit to horror movies. This interaction, this office, is everything that SRO Loyce Spells wants police at ETHS to represent. Alongside the other SRO at ETHS, Officer Grace Carmichael, Spells believes in establishing connections, building trust, and having dialogue with students.

“The bulk of our work is in the counselor, mentor role,” Spells says. “Not to say that we’re not busy doing the law enforcement side of things, because we are, trust me, but we are very intentional about building relationships and being a presence, a positive presence.”

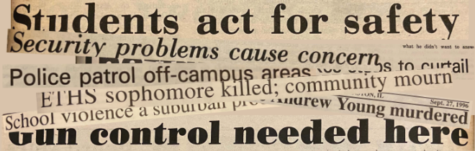

SROs were first employed in Evanston schools in 1966, and their prevalence in schools across the country has grown in the last 50 years. In 1975, as the Center for Education Policy Analysis reports, Evanston was in the one percent of schools that reported having SROs. By 2018, 58 percent of schools across the U.S. had SROs patrolling their campuses.

The purpose of these officers is to provide defense against external threats like school shooters. However, the City of Evanston emphasizes the specific need for SROs to be available and accessible to students.

According to the Evanston city government, “All School Resource Officers (SROs) are appropriately vetted, trained and guided by clear policy in order to cultivate relationships of mutual respect and understanding, and foster a safe, supportive, and positive learning environment for students.”

Notably, SROs at ETHS are funded by the Evanston Police Department. This is contrary to most other SRO programs, which are paid for by the school. The uniqueness of this situation matters because many conversations nationally about SROs are framed around the investment that a school is making into police. In this case, however, ETHS isn’t paying a cent, making the presence of SROs much more appealing to school administrators.

For Officer Spells, it doesn’t matter who funds his position. He firmly believes in his mission as an SRO and as an ETHS community member. Spells has been in the Evanston Police Department for 20 years. He has seen police departments across the country criticized for their frequent violence against black people. He has seen his own department called into question as well, especially in the aftermath of the 2020 shooting of George Floyd. He has seen protesters take to the streets; some simply protesting to stop the violence, with others shouting that “All cops are bastards,” and calling for the defunding or abolishment of the police.

In light of all this, Spells goes back to his roots. Growing up as a black man in America, Spells was far from immune to racist police officers. “The majority, if not all, of my encounters with law enforcement personally or through family and friends from six or seven years of age were bad. So I grew up despising law enforcement,” Spells explains. “It actually fuels what I do today. It guides me to be the officer that I never saw growing up.”

Spells sees working at ETHS as an opportunity to change the negative perception that Evanston youth have of the police; a perception that they may carry with them for the rest of their lives.

Additionally, Spells is working on a couple of changes to bring SROs closer to the student body. First, he hopes to add the decals of ETHS sports teams to the back of the SROs’ squad cars. Spells is also in the process of changing his dress code from the usual blue police uniform to less formal attire underneath the usual bulletproof vest.

The majority, if not all, of my encounters with law enforcement personally or through family and friends from six or seven years of age were bad. So I grew up despising law enforcement

— Loyce Spells

While these may seem like small changes, Spells believes in the importance of integrating SROs into school culture. “The blue uniform and the uniform in general sends this inadvertent message that ‘You’re not a part of us. You’re an outsider,’ as opposed to, ‘If you are part of us, you’re one of many in this community.’”

Spells wants police officers to be humanized and not alienated. He wants connections to be genuine and not forced. And he wants to be a resource, not a burden. “I really believe that you have two very good SROs at the school,” says Evanston Police Chief Schenita Stewart, who was appointed in late September. “And I think it’s important to clarify that because, in the past and in other agencies I know of, they’ve put [the role of SRO] off to get [bad officers] off the street.”

Chief Stewart brings up an important point about the credibility of SROs: many police departments assign their least trusted officers to work in schools. Therefore, instead of doing extensive and necessary training on how to properly interact with students, officers are thrown into schools, essentially as a punishment. This offers a semi-explanation for the viral stories and videos of police harming students in schools. Stories like the one of Brian, an 11th grader in Philadelphia who had an argument with an SRO about using the bathroom without a pass. The disagreement resulted in the officer throwing Brian to the ground and putting him in a chokehold.

Spells believes that isolated incidents shouldn’t define his role at ETHS. “Are there people who have bad encounters with law enforcement? Understood. But the presence of Loyce Spells, the presence of Officer Grace Carmichael, is not causing harm to anyone.”

Spells’ reaction to those incidents only solidifies his belief in the function of SROs. However, while he sees the benefit of his presence at ETHS, others don’t. Many Evanstonians consider SROs as a threat to the student body, doing more harm than good. This sentiment is exemplified in the work of the Moran Center, an Evanston youth advocacy non-profit and outspoken opposer of SROs.

In a study published in 2020, the Moran Center laid out its argument for removing SROs from ETHS. “When armed law-enforcement officers or SROs are employed in a full-time capacity on-campus, they inevitably become involved in situations where their involvement is unwarranted and causes matters to escalate unnecessarily,” the study says.

This rationalization brings up another crucial factor in the conversations around SROs: the school-to-prison pipeline. The Moran Center argues that the presence of police at ETHS directly results in more arrests, which sends teenagers into the criminal justice system. They say that students at schools with SROs are much more likely to be arrested for discretionary criminal violations like disorderly conduct or battery than schools without SROs.

Furthermore, the study questions the main purpose of SROs, which the ETHS website says is to “protect students and staff from external threats, such as a school shooter on campus.”

“While many school districts have created and maintained SRO programs to address [external threats], the hard truth is that there is no research or data establishing that SROs make schools safer or play a role in preventing school violence,” the study declared.

This is a big talking point for people who oppose the presence of SROs. It also is an uncomfortable truth for the students and staff who want to feel safe in the case of a shooting at the school.

The ETHS community is especially wary of guns as the school approaches the one-year anniversary of last year’s lockdown. That fateful morning, ETHS students and staff hid in corners of dark rooms, awaiting and dreading who might come through the door next. I sat in the corner of North Cafeteria, and I will not soon forget the silent tension and frightful whispers as we tried to figure out what was going on. We watched as police officers with automatic weapons patrolled the halls and the exterior of the school. It felt dystopian, surreal, and absolutely terrifying. And finally, after several hours of tense silence, we were sent home. I had never been closer to the reality of school shootings.

Since then, there have been a series of violent tragedies across the country. It has been seven months since the Uvalde, Texas shooting that killed 19 elementary school students and two teachers. It has been over five months since the July 4 shooting that killed seven people less than 30 minutes from Evanston households.

Violence in schools and across communities has instilled fear in children and adults alike. Young students practice lockdown drills before they know how to do multiplication, and parents can’t even guarantee that their child will come home at the end of the school day. Furthermore, to this point, there has been no sufficient response to this violence. Parents would love to believe that SROs are protecting their children, but as the Moran Center says, they can’t promise students safety from an external threat.

So, if it’s proven that SROs won’t prevent a shooting, is there any benefit to having them at ETHS in the context of guns and outside threats? Chief Stewart believes so. “There have been a few incidents of weapons being recovered on school grounds…if this was a situation where there weren’t firearms recovered, I would say, ‘maybe we don’t need SROs.’ But I don’t think we’re at that stage yet,” Stewart says.

The way Stewart sees it, SROs are necessary in a school that has had multiple guns found on campus in the past year. She cites a situation just a few weeks ago when a student was found with a gun shortly after the school day ended. Those are the situations, she says, that an SRO is needed in.

If it’s proven that SROs won’t prevent a shooting, is there any benefit to having them at ETHS in the context of guns and outside threats?

— Schenita Stewart

However, Stewart sees a world where SROs might not be necessary at ETHS. As a longtime black Evanston resident and ETHS alum, Stewart understands what it’s like to be at ETHS in the presence of police. Much like Spells, she has had scary encounters with police over the course of her life. Because of that, Stewart is not naive about the inherent dangers of policing in schools. For now, though, Stewart is satisfied with the status quo in Evanston and pleased to have passionate officers in the school.

While everyone raves about the ETHS SROs, it doesn’t address the broader problem that the country has with policing in schools. However, Spells has a vision for how to combat those issues. He wants to put an end to police department practices that put the least trusted officers in schools. He wants universal training to prepare officers to work in a school. And most importantly, he wants passionate SROs like himself, who care about the students that they interact with every day.

For Spells, the key is that “you prepare [SROs] to succeed in that role. It’s not just that you hope that they will. It’s that the police department and the city along with the school district work together to prepare the SROs to succeed.”

Overall, the Moran Center raises major concerns about the importance and effectiveness of SROs. And as the discussion around police remains a heated issue, the best thing that Evanston police can do is stay focused on the connections that they make and the community that they build.

As Chief Stewart steps into her new role, that community is her number one priority. “The understanding that our actions when we wear this uniform can not only affect one person,” Stewart says, “but a family or generations of people that think a certain way. And that is the day to day contact and respect [that] we have to build back.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.