Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

‘Microcosm of the world’: Evanston as a political ‘proving ground’

January 28, 2022

Evanston was shaped by both perpetrators and trailblazers, all of whom played an instrumental role in forming the city we call home. From real estate practices to voting tendencies, Evanston functions in the ways that it does as a result of its history with civic engagement and local policy choices.

Evanston’s historical perpetuation of housing discrimination

Since its founding in 1863, Evanston has been perceived as an emblem of opportunity. From the town’s locational assets—Northwestern, Chicago and Lake Michigan—to its ambitious and business-oriented citizenry, Evanston has garnered a reputation for being one of the most productive towns in the nation.

At the core of Evanston is its neighborhoods: the life-blood of the city. Roots run deep here, and it’s obvious why. On almost every block, there appears to be an ivory-brick church enshrined in old-English handwriting or a house whose porch splinters at the base, a physical representation of its use over the decades. Neighborhoods are symbolic of a city’s history, and in Evanston, our neighborhoods are monoliths of a complicated past—one of segregation and progress, of inequity and enfranchisement.

When Evanston’s Black community began to emerge in the late 1880s, reaching a population of approximately 125 people, they lived amongst a relatively integrated society.

“Everyone lived everywhere [because] Evanston was very rural before 1900,” Dino Robinson, founder and executive director of Shorefront Legacy Center, an organization aiming to archive the Black history of Chicago’s North Shore, says.

As larger swaths of African Americans began to migrate into Evanston, things began to change.

“By 1900, there was a demarcation, where there was [an incentive] to push groups of people in certain areas of Evanston, the most visible group being the Black community,” Robinson shares.

As racist sentiment began to grow in Evanston, so did its population. The beginning of the 20th century marked a period in which increasingly high numbers of Americans switched from renting homes to owning them, and Evanston provided both the land to develop houses and the opportunities to be economically successful. For Black families in particular, home-ownership was a way to generate decades of wealth, making up for the potential wealth lost to chattel slavery.

“[There was an] extraordinary value for ownership of property. [It] was the root of power, and the absence of property was the root of disempowerment,” San Diego State University history professor Andrew Weiss says. “[Property was] rooted in the experience of former enslaved people in the South who [had been] prevented from gaining property,” Weiss continues. “[So] there was this long standing tradition in value for ownership that is rooted in Black communities, and that was [also] true in the urban North as well.”

As Weiss explains, homeownership was deeply valorized within the Black community, but in areas like the American South where lynchings and Jim Crow permeated Black welfare, it was almost impossible to own property and build financial prosperity. A culmination of these financial struggles for Black Southerners, in addition to the growing industrial opportunities of the North, generated one of the largest migration movements in the United States, known as the Great Migration.

“Approximately six million Black people moved from the American South to Northern, Midwestern and Western states [between] 1910 and 1970,” the National Archives wrote.

For those who moved North, many found themselves in major cities like Chicago, and eventually in its surrounding suburbs, particularly Evanston. Its opportunities and “safe haven” atmosphere blanketed Black families from the horrific violence they faced elsewhere in the country. Evanston wasn’t exempt from its own forms of discimination, however. Evanston was in the process of pushing certain groups, as Robinson describes, into specific areas, providing Black families opportunities to own homes but within strict geographic limits.

“Unlike many suburbs that sought to exclude African Americans altogether, leading members of Evanston’s real estate establishment played a role in the growth of Evanston’s African American community,” Weiss wrote in his 1999 dissertation titled Black Housing, White Finance.

Like Weiss theorized, Evanston differed from adjacent suburbs because the city already had a well-established Black community by the time the Great Migration began. Evanston wasn’t exclusive in the sense that the town refused to sell homes to Black buyers—in fact, real estate agents encouraged their ownership—but the city was exclusive about where Black families could live.

“Evanston’s white real estate brokers apparently developed a practice of informal racial zoning. In effect, they treated a section of west Evanston as open to African Americans, while excluding them from the rest of town,” Weiss wrote.

Confined to land between the sanitary canal and railroad tracks, clear geographic barriers limited Black suburbanization and integration into the rest of Evanston, and it appears this strategy of informal racial zoning was effective.

“Between 1910 and 1940, there was not a single area of African American expansion outside of west Evanston, in spite of Black population growth of almost 5,000,” Weiss reports.

In addition to real estate agents, Evanston’s white bankers, builders and residents played active roles in restricting Black expansion. For one, “banks generally refused to make mortgage loans to Black households seeking to buy homes on blocks that were not viewed as ‘acceptable’ for Black people,” Robinson says.

Additionally, Evanston builders could refuse to construct homes for Black homeowners in areas outside of west Evanston.

“Builders did not sell properties to Black households if the homes were outside the area set aside for Black people,” Weiss wrote. “Builders constructed more than 1,400 new homes in northwest Evanston during the 1920s and 1930s, none of which were sold to Black households.”

When bank and building discrimination weren’t effective enough in restricting Black settlement, whites mobilized together to establish neighborhood improvement associations. Ironically, these associations didn’t improve neighborhoods; they segregated them.

“South of Church Street and west of Asbury Avenue, white homeowners formed the West Side Improvement Association ‘to preserve [the neighborhood] as a place for white people to live.’ As part of the plan, they formed a syndicate to buy homes that were at risk of being sold to a Black family,” Robinson and Evanston History Center Director of Education Jenny Thomson wrote in a 2020 City of Evanston report titled Evanston Policies Directly Affecting the African-American Community.

The effect of these policies were stark.

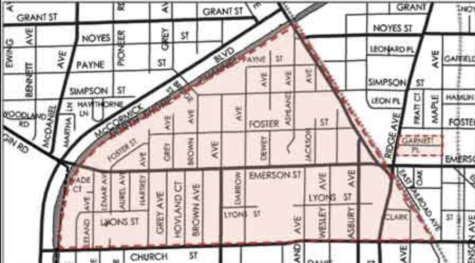

“By 1940, census data showed that 84% of Black households in Evanston lived in the triangular area. This area was highly segregated—95% Black.” (This is shown in image 1).

In the report, the “triangular area” demarcated a specific region where Blackness was present in Evanston. It was a section between the North Shore Channel (sanitary canal), East Railroad Ave. and Church Street. When intersected, the streets formed a triangle shape.

Evidence indicates that the 1940s marked a point where Evanston crystalized its segregated neighborhood dynamics. Amongst the discriminant involvement of realtors, banks, builders and citizens, the City of Evanston rolled out its most racially codified policy yet: redlining maps.

Following the economic short-falls and property foreclosures of the 1930s, largely due to the Great Depression, the federal government established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (H.O.L.C.) to evaluate various American neighborhoods and their perceived level of financial lending risk. H.O.L.C. deployed federal examiners to “consult with local bank loan officers, city officials, appraisers, and realtors to create ‘Residential Security’ maps of [major cities],” writes the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. One of these cities was Evanston, who published its map in the 1940s.

“The advent of the redlining maps, the final, whole map [being published] in the ‘40s, basically codified where the Black community was supposed to live,” Robinson states. “[If you look] at all the redlining maps [published] across the country, all the red areas always said, ‘This area would be better if it wasn’t for the Negro population.’ So, that was consistent. You can see how that codified a Black community and [also] how to decimate that Black community, [which was always pushed into] a remote zone. It informs the funding there, it informs the real estate agent where to push Blacks and [also] where to push whites if they’re still there.”

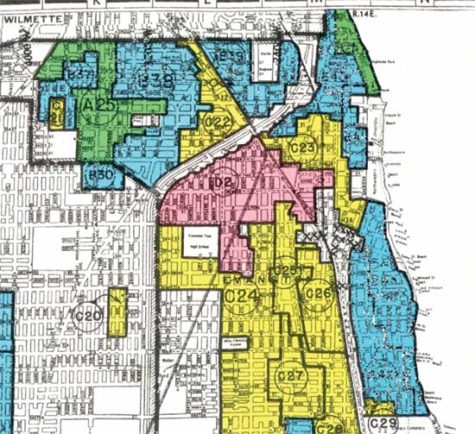

Redlining maps served two purposes (refer to Image 2). For one, they identified specific neighborhoods as high or low risk for investment; to the right of all redlining maps was a key which presented four colors—green, blue, yellow and red—and each color’s corresponding information. All neighborhoods colored red were “high risk” and all neighborhoods colored green were “low risk.”

The second purpose of the maps: segregation. In the surge of suburbanization and ethnic growth in Evanston, agitated whites needed legal ways to prevent integration in their affluent neighborhoods. Redlining affirmed racist sentiments in Evanston by pushing Black residents into “high risk” red areas. When Black Evanstonians requested support, either for construction or loans, it was often limited because they lived in “high risk” zones.

What is particularly striking about Weiss’ findings are the hastened and seemingly conflicting actions of white Evanstonians. Evidently, vigilant racism plagued the brains of many, made visible by their discriminate actions in real estate, construction and private associations. However, they also contributed positively to Black welfare once barriers were placed between them that ensured a segregated city.

Mortgage lending was perhaps the most widely used practice amongst white elites. As Weiss wrote, “they lent money to Black home buyers, which gave them a financial stake in the Black neighborhoods in Evanston and expressed their faith that Black borrowers were a sound financial risk.”

In addition, whites participated in philanthropy, donating money to necessary material goods.

“During the 1910s and 1920s, white donors supported campaigns to establish a Black hospital, a boarding house for single Black women, day care services for Black children, and a YMCA to provide recreational facilities for Black youth,” Weiss wrote.

While both mortgage lending and donations helped strengthen Black welfare, it also exuded elements of white benevolence and supremacy. Whites felt that participating in charity made them exempt, either from the problems they created or from a solution to prevent potential conflict. Regardless of their intent, research indicates whites simultaneously uplifted and destroyed Evanston’s Black community.

One final question remains: why were whites so actively involved in Evanston’s Black housing market?

It appears, in the context of the Great Migration, whites were attempting to contain a movement they couldn’t stop. As Evanston’s population grew in diversity, discriminatory housing policy was seen as a remedy to control an emerging racialized population. As Cora Watson, former president of the North Shore Community House, explains, “Whites didn’t want the colored,” but “they couldn’t keep us from moving in.”

Quoted in Weiss’ dissertation, Caledonian Martin, a former resident who moved to Evanston in 1909, noted, “Evanston, the beginning of it, was for rich people to help and not for the colored to come out and live . . . but we get here, and we stay.”

Mobilization of a city

The racial disparities that appear at the basis of Evanston’s institutions are commonly attributed to the presence of prejudicial behavior within the housing market. Often viewed as an indication of immoral loopholes working outside the confines of the law, “de facto segregation”—or racially motivated practices that were not legally imposed—existed as the outcome of explicit public policies that intentionally separated Black families from whites, commonly referred to as “de jure segregation.”

Blatant discriminatory practices upheld the ideals of former city planners.

“Discriminatory practices and a lack of affordable housing crowded Blacks into the west side where the demand was greater than the supply, enabling landlords to neglect housing stock and raise rents,” Mary Barr, a Kentucky State assistant professor of sociology, wrote in her book entitled Friends Disappear. “Public policy and private action had created a visibly segregated city.”

From the impacts of Northwestern University and the city’s crucial role in the temperance movement, Evanston’s liberal reputation was well-defined from the beginning, even while racist housing practices were being implemented.

Throughout its history, Evanston residents have protested racist housing policies in the city, often only earning partial victories along the way.

“The Black community was fighting against segregated housing as early as 1905. The movement was always evolving,” Robinson says.

By the 1960s, in the wake of redlining and other racist real estate practices, many Evanstonians were ready to push for less segregated housing practices.

Despite the implementation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, housing discrimination consistently proved to be the most persistent form of segregation in Evanston.

Inspired by civil rights movements that took place outside of the Chicagoland area, a number of residents from suburbs across the North Shore formed what became known as the North Shore Summer Project (NSSP), a campaign that began when activist Bill Moyer, alongside his North Shore based counterparts, joined forces to remove the barriers of injustice within the community.

“The story of the North Shore Summer Project and its aftermath is about a brave attempt to transform not only a de jure racist suburban housing market but also a de facto culture of exclusion. I argue that the NSSP’s most significant legacy was not the most obvious, the changing of housing laws and real estate practices, but rather its ability to galvanize hundreds of people—white and Black, particularly women—in an extremely organized fashion around an ethic of racial justice,” executive director of Housing Opportunities and Maintenance for the Elderly (H.O.M.E.) in Chicago, and former long-time executive director of the descendant of the North Shore Summer Project, Open Communities, Gail Schechter, wrote in her chapter of The Chicago Freedom Movement: Martin Luther King Jr. and Civil Rights Activism in the North. “This language of justice, laden with religious and patriotic underpinnings and an ethic of care that made others’ struggles one’s own, was especially appealing to those affluent, white North Shore residents who wanted to contribute to the electrifying energy of the Civil Rights Movement.”

With Bill Moyer as the project’s director and Reverend Emery Davis of AME Church in Evanston as chairman, the ambitious goals of the campaign were in the hands of several disciplined individuals.

“[In March of 1965], Moyer and Davis planned to reach out to everyone in the northern suburbs who had a house listed for sale. With over 1,000 houses on the market, they were going to talk to homeowners about whether or not they’d sell to a Black family, and how they felt that their neighbors would approach the situation,” Schechter says.

In February of 1965, a total of 75 North Shore realtors were interviewed by those involved in the North Shore Summer Project. The vast majority of North Shore realtors agreed that the values of the NSSP aligned with their personal beliefs in regards to integration. The realtors positioned themselves as strictly accommodating to the desires of the seller. They expressed the community’s unwillingness to become a non-restrictive, welcoming haven.

The report, released on Aug. 29, 1965, read, “Other vital facts that have come to light are that realtors do not do the will of the homesellers whom they claim to represent; realtors do the will of the realtor. Realtors do not do the will of the community; realtors do the will of the realtor.” It continues, “If realtors would exert as much leadership and pressure in a positive direction as they do in maintaining the status quo they have created, then our communities would be as open as they are now closed. The NSSP findings agree with a statement made by Louis A. Pfaff, President of the Evanston-North Shore Board of Realtors, ‘Times have changed, but the real estate industry has not.’”

Realtors do not do the will of the community; realtors do the will of the realtor.

— North Shore Summer Project report

Maintained and uplifted by local realtors, racist practices only satisfied the desires of a single demographic that contributed to the entirety of Evanston’s population. The North Shore Board of Realtors acted as gatekeepers that steered sellers in the direction of upholding racist laws.

Additionally, the NSSP was responsible for the opening of freedom centers, which delivered accessible services to those directly impacted by housing inequalities and other forms of discrimination, while promoting the ideals of freedom along various dimensions.

The work of the local grassroots organization was fueled by the compelling and dynamic energy at the heart of the campaign. Both nationally and across the North Shore, the fight to cease all forms of racist attitudes and policies was in full force.

Nonetheless, the success of the North Shore Summer Project was met with some skepticism and resistance.

“The North Shore Summer Project was an incentive to engage Black families to move into the North Shore areas to try to diversify and make a more inviting environment. However, it [was] met with mixed results. There were families that were excited about this. But if we really think about it, it comes down to resources. Why would a Black family move into a community where the resources are not there for them? They would have to move elsewhere or go somewhere else to [access] the services that are specific to them, as odd as it might sound,” Robinson shares.

“If I move to Wilmette,” Robinson supposes, “and I’m the first Black family that lives there, and I’m looking for someone to cut my hair, what barber would know how to cut my hair? I would have to leave the town and find someone that can do that. I may want to go to a church that more [accurately] reflects my culture and identity, and if these services are not there, why deal with that?”

Still, the limiting nature of change for Black folks in the area aside, the organization’s effort to shift local culture drew nationwide attention, including that of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Following his triumphs in several southern cities, King ventured North to continue his teachings, traveling across the various Chicagoland suburbs and inspiring the local community about issues regarding fair housing and equal education.

“King’s Chicago Movement had two goals: better conditions in Black neighborhoods and unfettered access to housing in white neighborhoods,” Barr wrote.

King’s ideas quickly flowed into Evanston politics as well.

“Evanston often functions as a proving ground or trying out space, like a little microcosm of the world outside our borders. That’s true with the Civil War. That’s true with World War One. These are all big, national, world events, and Evanston got its own little version of it,” Lori Osborne, the director of the Evanston Women’s History Project at the Evanston History Center, says. “When King was working on housing desegregation, specifically, and I believe it’s connected with the Chicago housing reform movement, Evanston was working on the same thing. Evanston was seeing these national forces and going, ‘Well, hang on a minute. This is happening here. Let’s take this on.’”

July 25, 1965 marks the date of King’s speech on the Winnetka Village Green, which garnered a large audience of locals. With the support of the North Shore Summer Project, over 10,000 locals were in attendance. Equally as exceptional as the number of individuals in attendance were the serene conditions at a time of frequent ferocity and cruelty in the presence of King’s well-intended conversations.

Evanston was seeing these national forces and going, ‘Well, hang on a minute. This is happening here. Let’s take this on.’

— Lori Osborne, Evanston Women’s History Project director

King’s ideas quickly flowed into Evanston’s politics. However, the assassination of King on April 4, 1968 caused a wave of disruption across the entirety of the country and sparked a more local discussion regarding fair housing in Evanston. King’s progress paved the way for the future of equitable housing laws and racial equality.

On April 7, 1968, just three days following the death of Martin Luther King Jr., Evanston residents gathered to march as both a sign of gratitude and respect while participating in the freedom movement.

The designated route began at Emerson Street and McCormick Boulevard, where participants continued southeast before entering Evanston’s Raymond Park to attend a celebratory gathering. Two days after the march, Evanston schools were shut down to honor the progress directly attributable to MLK.

Almost simultaneously, the Fair Housing Act of 1968 passed on April 11 reinstated and broadened the rights protected by the Civil Rights Act just four years prior. The implementation of the Fair Housing Act credited to President Lyndon B. Johnson ultimately prohibited discrimination by housing providers and other entities, whose practices made purchasing housing nearly impossible on the basis of race, religion, national origin and sex.

Without the implementation of a fair housing ordinance at the local level, Evanston residents continued to fight, with a city council vote as their desired outcome.

Several days later, on April 29, 1968, Evanston’s city council gathered to conduct the voting of a new ordinance, an official form of legislation that would solidify the illegal practices written in the Fair Housing Act.

Fifteen to one, the 1968 ordinance was passed into law.

Mobilization was an integral part of the push for change. That said, which face of Evanston ultimately showed itself as a result: surface level progressivism or real sacrifices and commitment to social change?

“If it wasn’t for the Black community to raise those vocal challenges, it may have not [passed],” Robinson continues. “[If Black residents hadn’t advocated for themselves], I think there would still be the status quo and those who control the narrative would still say Evanston’s a progressive, liberal city without actually having to do anything.”

A former Fifth Ward alderwoman and national leader in the push for reparations, Robin Rue Simmons notices Evanston’s great potential, and with the right vision and leadership, she believes Evanston can be transformed into a more liveable and equitable city. While Simmons has seen incremental changes, these changes didn’t break the fundamental truths at the heart of the city. Simmons’ ideal reparations bill directly targets racial and educational gaps, forming a bridge between household incomes and homeownership rates.

Simmons proposes, “We’re doing a reparation in direct correlation to our harm, which is housing and zoning here in Evanston.”

Evanston: A city shaped by political engagement

In 2012, Evanstonians had the opportunity to vote on a referendum to build a school in the city’s Fifth Ward, an area which has been without a neighborhood elementary school since 1967.

By affirming the referendum, the Evanston/Skokie Consolidated School District 65 would have been transformed into a more equitable institution for all children. But when the chance to make the difference within the Fifth Ward was dropped into Evanston residents’ laps, the referendum ultimately failed, with 54 percent of Evanston voters saying ‘nay.’ This wasn’t the first time that such a referendum had been brought to Evanston voters, each time resulting in the same outcome: no new school in the Fifth Ward.

In a town known for its progressivism, in which 84 percent of its residents voted blue in 2012’s presidential election, how is it possible that a campaign to make its public education system more equitable failed?

This vote—and other moments through Evanston’s history—may be explained by a sociological phenomenon called interest convergence, coined in 1980 by the “godfather” of critical race theory, Derrick Bell. As explained by New York Times reporter Chana Joffe Walt, the interest convergence theory argues, “the only times we ever see an expansion of rights for Black Americans is when white Americans benefit, when interests converge. If white Americans don’t see something in it for themselves, nothing changes.”

In terms of the referendum, interests did not converge. While almost 70 percent of the Fifth Ward voted yes, the Sixth Ward and Seventh Ward, which make up the city’s predominantly white North Side, only saw 35 percent of its residents vote in favor, according to the Daily Northwestern. Clearly, white Evanstonians did not see enough in it for themselves to vote in favor of opening the new school.

However, when looking at Evanston’s political track record in national and state-wide elections, the loss of the referendum seems like it should be an outlier. Since the city’s founding, Evanstonians have always had a strong focus on human rights, which only intensified in the mid-20th Century.

“The ‘50s and ‘60s in Evanston was an interesting time; it mirrored a lot of what was happening in the nation,” Robinson says. “There was a movement in Evanston, much like the rest of the country, where you had a political shift from the African American community mostly supporting the Republican Party to that of the Democratic Party. At that time period, we saw the Republican and Democratic Parties have a massive shift of ideology.”

Before the transition, the Republican Party was strongly focussed on achieving unified public thought, while the Democratic Party was centered around a belief in individual rights and state sovereignty. The parties’ belief systems swapped in the late 1920s, in an ideological shift known as party realignment. At this time, the Republican Party held the support of most Black voters, but the efforts of northern Democrats to fight for civil rights led to a realignment of Black voters, as well as other voters whose core values were focused on human rights issues, from the Republican to the Democratic Party. In the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, between two-thirds and three-fourths of Black voters supported the Republican candidate. However, by 1936, the number dropped to 28 percent, according to the History Archives of the United States House of Representatives, exemplifying this realignment within Black communities across America. As noted by Robinson, Evanston was no different.

“Earlier, before the ‘50s, the Republican Party was more associated with [the] common good [and] how to help the middle class and society. [They] believed in unions, fair work, fair wages and equality. But that shifted from one party to another,” Robinson says. “So that [was reflected] here in Evanston, and by the 1950s and 60s, we had a growing movement of what we call today the Civil Rights Movement. So, you had residents that have lived here for generations trying to push back even more so about fair housing, about employment opportunities, [and] about fair treatment in Evanston.”

While the national and local realignments started with a shift within the Black community, white Evanstonians followed suit.

“In the white community, you really start to see the change in the late 1950s with a new era of civil rights work and human rights work,” Osborne explains. “In Evanston, that’s particularly focused on issues of housing, segregation, school segregation and the need for integration—or what they think of as more fair allocation of school resources and geographic boundaries for schools.”

By 1964, both Evanston and Chicago were voting blue, but Illinois remained a Republican state. Much of Evanston’s liberalism was visible through community protests and mobilization, such as the North Shore Summer Project in 1965 and the community’s push to integrate its schools.

And yet, in a time when the political beliefs of both Black and white Evanstonians realigned to focus more on civil rights, the needs of Evanston’s predominantly Black Fifth Ward were being ignored, especially when it came to its neighborhood school, Foster School.

Foster School, which opened at 2010 Dewey Avenue in 1905 was almost entirely Black for the majority of its lifespan. The school’s demographics, which reached 94 percent Black by 1960, were a curated product of the city’s racist housing practices that dominated the early 20th Century.

Around the same time as the North Shore Summer Project, District 65 was making plans to integrate its schools—an action that, at the time, matched the political beliefs of the city as a whole. Foster School was central to these integration plans, and the only Evanston school chosen to be broken up through these practices. It would first house an experimental kindergarten program, into which families from across the city could place their children. Once the results of this kindergarten program came back positively, the district moved to make all of Foster a laboratory school, accepting students from across the city. Just like that, in the midst of two years, the Fifth Ward had lost one of its main community centers. Its children found themselves needing to be bussed to school across Evanston and divided amongst themselves between elementary schools on the city’s North Side.

“If you look on a map of the school area zones, there’s only about four blocks exed [where] those kids living there will go to Lincolnwood School. A block over, they’ll go to Walker. Another one across the way will go to a different school,” Robinson explains. “All [of the] Fifth Ward was broken up into five different school zones. So that splits up a community. It dilutes the power structure that’s there—the PTA power structure—and also the influences that those families have with their children and teachers.”

Not only did the move strip Fifth Ward residents of political capital and community, the bussing policy also had a tremendous strain on student relationships and growth outside of the classroom.

“It looks good in class, but in the community, [the students are] not there. Parents of those students are not there to walk their kid to school, or hang out afterwards or have coffee with the other mothers and fathers that are dropping off their kids. So those bonds and those relationships are not being made,” Robinson says. “There’s no connectivity within a classroom, and after school activities might be limited because of that.”

Despite the fact that a neighborhood school is integral to the lifeblood of a community, and that Foster School in particular was a place of power and connection within the Fifth Ward, the area has now been without a neighborhood school for more than half a century. While there have been multiple referendums proposed to build a new school since Foster School closed, every time Evanstonians vote, the proposal is shot down. Somehow, in a community that claims to be focused on civil and human rights, not enough Evanston residents see a Fifth Ward School as an institution that is not only worth having, but vital to community growth and racial equity.

“[Foster School] was this vibrant community institution. It was a gathering place, where people met and formed those community bonds that make for a strong, vibrant place,” Osborne says. “I think people meant well, [but] I honestly believe there was a certain lack of understanding or real focus on the needs of the Black community and what happens [when] those community institutions are gone. And you can still, today, hear people talk about it. They’re basically grieving the loss of these places.”

Negligence of the needs of the Fifth Ward community is not solely focused on Foster School. A little more than a decade after the institution was transitioned into a laboratory school for the whole Evanston community, leaving the Fifth Ward residents without a neighborhood school, another community staple was withdrawn. The library branch, which opened in the Fifth Ward in 1975, was closed within 6 years of its opening.

In 2020, discussions about creating an equitable library system gained traction. In an effort to make the library’s resources more accessible to all parts of Evanston, the Evanston Public Library’s Board of Trustees unanimously voted to close the organization’s branches on Chicago Ave. and Central St., both of which have historically served predominantly white communities. The resources were redistributed to the newly implemented branch within the Robert Crown Community Center, which, located on the corner of Main St. and Dodge Ave., is significantly closer to the more diverse side of the city.

“There were suggestions to close the branch library on Central St., and there was huge pushback,” Robinson says. “But at the same time, there was a Black community that wanted a branch library put back in the Fifth Ward that once used to be there. And the community was, in general, told to ‘just be patient, your turn is not now.’”

But in terms of turns, how long does one last? In a town known for its political progressivism, Fifth Ward residents have been waiting for a library in its ward since 1981.

“So [there’s] that type of pattern of, ‘Wait until we get this done first. That benefits the greater [white] community, then we’ll get to yours eventually,’ and eventually never comes,” Robinson says.

Throughout Evanston’s history, the Fifth Ward has continuously been left waiting. Whether it was for true integration, a school, a library branch or something else entirely, Evanston’s claimed progressive beliefs have never been deep or radical enough to truly make the city equitable for its residents of color.

“I look at it as a sense of privilege,” Robinson says. “What I’ve seen with my research over the last 25 years is that there seems to be a pattern with any type of new initiative, building or services. It focuses [on] helping benefit those from a privileged background [rather] than those who’ve been deprived of those same privileges—mainly the Black community.”

kathy hayes • Feb 1, 2022 at 7:25 pm

well done. thank you for your work

Julie • Jan 29, 2022 at 7:55 pm

Incredibly well written pieces by all 3 of these young women. Huge congrats!!