Daniel Taylor regains freedom, sustains love for learning during wrongful conviction

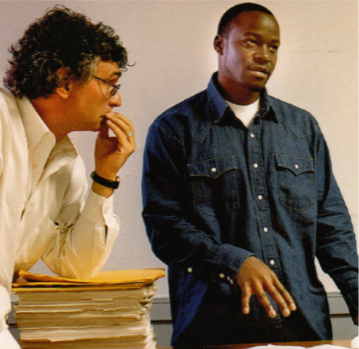

Photo courtesy of Daniel Taylor

Taylor in 2001 with Chicago Tribune reporter Maurice Possley.

April 3, 2020

On a blustery February day, I met Daniel Taylor at Silverman Hall on Northwestern’s campus, one of the buildings he works in during the week. His upbeat demeanor was a welcome contrast to the rather gloomy weather. While I had seen him speak about his life before at public forums, this was our first in-person conversation and my first time understanding the depths of Taylor’s strength, even as a young boy in Chicago in the 1990s.

At 17 years old, Taylor was convicted of a double-homicide he did not commit and was stripped of 21 years of his life.

“Taylor’s case stems from a November 1992 double murder that police and prosecutors said was committed by eight young men,” according to the Chicago Tribune. “Taylor made a lengthy confession that he said was coerced by veteran detectives. However, other police officers testified that Taylor was in police custody at the time of the double murder.”

Without any time to dream about his future or explore a career, he was thrust into adulthood before he had even reached legal age.

“I do feel like I missed out on a lot of experiences that a normal person would have,” he explains. “I wanted to be a boxer. I wanted to graduate high school and then I wanted to turn pro.”

Though he was deprived of the chance to experience freedom, he used his time in prison to develop his love and appreciation for learning.

“When I got to prison they did a placement test in school and I scored at a third grade level,” he says. “My passion came because I wanted to understand what was being said in court…a lot of times when I was at trial I would be sitting there and I didn’t know what was being said.”

Given his circumstances, Taylor couldn’t learn for leisure; he learned in order to survive.

Over the course of several years, Taylor studied words from the Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, memorizing not only the term but its antonym, synonym, prefix and suffix.

More specific to his fight for freedom, however, he studied the Black’s Law Dictionary.

“It was either learn, or go down. I took it that way because there was a time where I had to represent myself so to speak,” he affirms. “In the court system, your lack of knowledge is not an excuse.”

As a result of his own determination and drive, along with help from Northwestern’s Center on Wrongful Convictions, Taylor regained his freedom on June 28, 2013.

Today, Taylor is questioning and reflecting on the factors that played into his prosecution, with race being at the forefront.

In a court hearing, the person tried to presumed innocent until proven guilty. Taylor downplays that notion, putting air-quotes around it.

“When it comes to the jury, they say it’s a jury made up of your peers. If I’m going to have a jury of my peers it’s going to be a jury of people that are financially burdened, poverty-stricken. believe that I was stereotyped,” Taylor says. “Going through what I went through and my experiences through the court system, it’s almost as if if you’re black, you’re guilty until proven innocent.”

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, Taylor was the 90th person exonerated in Cook County since 1989. The Innocence Project states that 1 percent of the U.S. prison population, approximately 20,000 people, have been falsely convicted since 1980.

“In order for there to be a more accurate system, prosecutors need to be held accountable. I believe that if they were held accountable when someone has been intentionally wrongfully convicted, I think things would take a whole other turn,” Taylor says.

At 44, Taylor still resides in Chicago where he cares for his young son. He works during the week at Northwestern University. In his free time, he retains his youthful passions by skateboarding and continuing his pursuit of boxing.

Taylor feels it important to share his story with the world for those who are most vulnerable to institutions — young people. In his future, he hopes to write a two-part book and have a film created about all that he has endured.

He feels it important to discuss how in life, “putting yourself in a situation where you could end up fighting for your life in a way you never thought you would have to based on who you have surrounding you,” emphasizing the notion to surround yourself with positive influences.

Taylor recognizes how his years of imprisonment have shaped his current mindset. By reflecting on his past, he has been able to move forward. In a letter to his younger self, he offers the knowledge he wishes he had known in his youth.

“Life is always a learning experience. Going to prison will test you consciously, unconsciously, and mentally,” Taylor says. “I appreciate a hug, a handshake a little bit differently than other people because I know what it feels like to have them taken away.”