History teacher, SOAR coordinator talks school safety, the dangers of increased security

December 16, 2022

Teachers are vital to school safety. From the reassuring gestures given before unit tests to the warm “hellos” uttered in between passing periods, educators help students feel safe and seen in a space that has historically reinforced violence, control and fear. Because of teachers’ lived experiences as both students and educators, they hold wisdom that must be taken into account when discussing school safety.

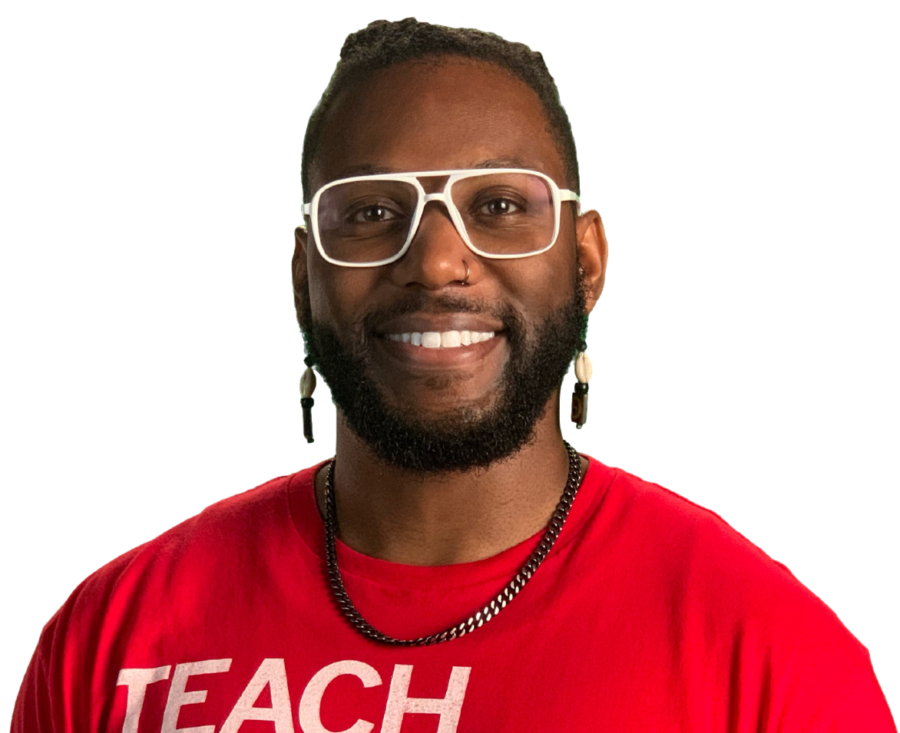

“I grew up during a time where I witnessed [some of the first] mass school shootings. I was in sixth grade when Columbine happened, and I remember coming home from school and watching the news and seeing kids running out of lunch. I was like, what is going on? How could this happen? [It] felt so strange to see students bringing guns into schools, and then to see students [being] murdered in school. It was such a strange reality for me to navigate. [When I became] a teacher at ETHS, there was a lockdown drill within three weeks of my first year. [So] from that time I was in sixth grade to my time as high school history teacher, I’ve understood what those dynamics are. So I’ve had this really interesting journey [with safety in school],” says ETHS History teacher Corey Winchester.

Winchester is currently taking a leave of absence to pursue his PhD in Learning Sciences at Northwestern University. In previous years, he has taught United States History and Sociology of Class, Gender and Race. Outside of the classroom, Winchester has served as the staff coordinator of Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR) since 2012. With such an extensive background at ETHS, he has experienced several aspects of the school’s culture. In fact, one of Winchester’s first memories of ETHS related to safety in school.

“In my first year [teaching] I was given a [history] textbook called The Americans. It’s a textbook that students typically receive if they take United States History honors. So I start flipping through the pages, and I get to a section in the back of the book that’s about new issues in the 21st century. And the topic is school safety. There’s a picture of my neighborhood high school in [Philadelphia,] called Bartram High School, of Black students walking through metal detectors. The conversation was about school safety, but with a firm focus on an inner-city school with predominantly students of color,” he says.

Winchester underscores an pertinent aspect of conversations surrounding physical safety in school. Like textbooks, many Americans perceive that gun violence is an issue that students solely in urban settings experience. This not only perpetuates myths that gun violence disproportionately occurs in areas where higher populations of Black and brown students live, but it is also factually incorrect. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, of the 318 school shootings committed between 2009-2019, 140 occurred in urban areas, 80 in suburban areas, 50 in rural areas, 48 in towns and 21 couldn’t be matched. Meaning, less than half of the total school shootings occurred in urban settings.

“School safety [has] been mythologized as an issue that we see only kids in urban settings experiencing, but [students in suburban and rural areas also] have to negotiate this reality where folks are bringing in guns in schools,” Winchester explains.

Regardless of where a school is located, it is imperative that all educational institutions enforce measures to protect students from guns without making them feel like highly surveilled spaces.

“Navigating around [violence] has been fairly normal in schools. [But] what was very different was how schools institutionally responded to those threats of violence. [Some schools responded] by installing metal detectors or increasing police presence in schools. [As a result,] schools then slowly became a highly surveillanced space. And that was a transition that I witnessed throughout my schooling. So from sixth grade to when I graduated high school, these were some of the things like, going through metal detectors, [that] made school feel like I was walking through the airport.”

Winchester attributes schools’ increased surveillance to 9/11, in which the federal government responded to al Qaeda’s terrorist attacks by developing an extensive security framework. Consequently, this affected how public spaces, including schools, were policed.

Why is it that when kids go to school, they have to learn how to protect themselves and operate from a place of fear?

— Corey Winchester

“9/11 really changed the dynamic for how folks thought about safety and security in the nation. Because of the terrorist attacks, the way that the United States responded with things like the Patriot Act, the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security, and in the policing that happened in multiple contexts, like from like airport security to increased security and government buildings, like all that also was happening at the same time. So we’ve seen this hyper policing of public spaces that I also think is important historical context to add in . . . So there’s been this trajectory of surveillance and policing public spaces. Schools, unfortunately, given the fact that we do live in a violent society, was also a place where that has happened.”

Like Winchester describes, schools in the modern era are surveilled similarly to public fora. But as schools across the country tighten their safety procedures through the inclusion of things like automated locks, metal detectors, high-depth cameras, and School Resource Officers (SRO’s) new problems arise: when safety measures increase, discipline often proliferates, too.

“When Michelle Alexander, who wrote The New Jim Crow, came to Evanston like a decade ago, she [talked about how] there are two institutions that criminalize in Evanston: the police department and our school systems. And there’s something to be said about that. I think what this requires is for us to really think about discipline differently.”

As referenced above, The New Jim Crow is a sociological text depicting the legacy of mass-incarceration in the U.S. criminal justice system spawned by profound inequities created after the abolition of slavery, including Jim Crow laws and the War on Drugs. Unfortunately, as our nation’s criminal justice system expanded to hold more prisoners, our schools transformed with it. National concerns about crime and discipline led schools to adopt more punitive policies, resulting in the funneling of students into the carceral system in a phenomenon called the “school-to-prison pipeline”. According to the ACLU, the school-to-prison pipeline is “a disturbing national trend wherein youth are funneled out of public schools and into the juvenile and criminal legal systems. Many of these youth are Black or Brown, have disabilities, or histories of poverty, abuse, or neglect, and would benefit from additional support and resources. Instead, they are isolated, punished, and pushed out.”

Winchester expands on this concept, highlighting the dramatic effect punishment and discipline has on students’ futures if they are convicted of a crime during high school.

“There’s two places [where students] get in trouble on some type of permanent file record. It’s [with our] schools, and it’s with our police. And so that has implications if you’re in school and you’re looking to apply to colleges, trade schools and jobs. So I think, in that respect, how we police in schools also mirrors how folks are policed and criminalized in real life. If you’re convicted of a crime and you’re applying for jobs that [record] has implications on job applications . . . It has implications on access period.”

As schools navigate discipline and the criminalization of youth, an important question must be asked: how are students emotionally impacted by punitive policies? When students feel that they can’t fully express their identities from policies that regulate how they physically show up, it affects their sense of emotional security. According to Winchester, these were the circumstances that led ETHS to remove the dress code in 2016.

How we police in schools also mirrors how folks are policed and criminalized in real life. If you’re convicted of a crime and you’re applying for jobs that [record] has implications on job applications . . . It has implications on access period.

— Corey Winchester

“[Students not feeling like they could express their identities fully] is one of the things that led us to get rid of the dress code policy. School safety doesn’t just look like police presence in school, but it’s also how we put in laws. In high school, we have policies or rules [that decide] what kids can and can’t do. And some of that was coming down to how students’ bodies were being received by folks. And if you look at it [from a racialized lens], mostly Black and brown kids were policed more than white students based on what they were wearing,” he says. “Part of the dress code policy said that you couldn’t wear hats in the buildings, and that was something that impacted black males. And [that’s] not to say that other folks didn’t wear hats in the building. But the kids who were disproportionately told to take off their hats were Black male students. White male students and white female students also wore hats but they weren’t being policed for it in the same way. That’s just one example of how people’s identities are associated with particular actions, particular clothing items. We begin to racialize how people are showing up. And that’s a problem.”

The racialization of clothing can impact students in macro ways.

“In school spaces, we don’t always have the opportunity to express our identities fully. For example, we witnessed how ETHS policed bodies during graduation. I think most folks are aware that the administration didn’t let an indigenous student walk during graduation because he wore an important religious symbol of his culture.”

Winchester is referencing last year’s graduation where senior Nimkii Curley did not receive his diploma on commencement day for embroidering his cap with traditional Ojibwe floral beadwork and an eagle feather. According to the Evanston Roundtable, the eagle feather “is sacred and used for prayer. [It] represents generational respect, continuity and responsibility to one’s community.” For these reasons, when event coordinators and safety personnel asked him to remove his cap because ETHS does not allow students to modify their caps and gowns, he refused. As a result, Curley was directed to sit in the bleachers with his family until the ceremony ended.

“[A] safe school wouldn’t create those types of violence,” Winchester says, finishing his thoughts about anti-indigenous actions at ETHS.

For him, schools have a long way to go to become safe environments both physically and emotionally. But in the absence of equitable, safe schooling, teachers and students have curated meaningful relationships to move beyond an institution that historically dehumanizes.

“At the end of the day,” Winchester concludes, “your human connection to me is on a human level, as opposed to a level that’s predicated on power. So teachers and students, we’re doing this work in a way that is based on relational trust. Understanding one another’s humanity [is about] seeing each other as equals in a level of respect towards one another’s experiences . . . If we began to make sure that our laws actually reflected some of these human relations that we have with one another, [we’d begin to approach safety with a more humanizing lens]. But until we examine power, and understand how power is used as a tool for dehumanization, we can’t make power work in ways where we exist in humanizing relations with one another.