Evanston holds rich history

Suffrage, gangs and prohibition.

A lot went on during the twenties in Evanston.

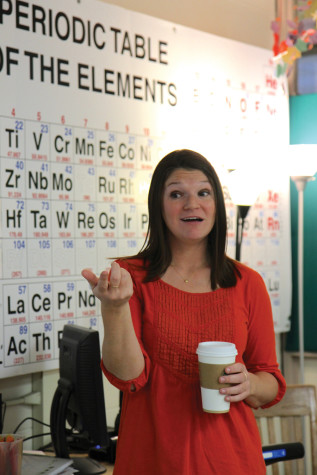

“Ever since Frances Willard was a little girl she thought women should vote,” says Janet Olsen, volunteer archivist at the Frances E. Willard Memorial Library and Archives. “Frances Willard brought suffrage into the temperance movement.”

Even though prohibition began in 1919 after Willard’s death in 1898, it was the work of herself and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

Willard was also a women’s activist and encouraged females to gain the right to vote and get politically involved. She is a very big reason why women have the vote today. In fact, many people of the WCTU did not believe women should vote, but it was Willard who convinced them otherwise and ended up being the second president of the WCTU.

“She always wanted to learn. Her mother encouraged all of the children to keep a diary and write down their thoughts,” says Olsen. “She wrote all the time. I think she thought of herself as more of a writer.”

Willard wrote books teaching women how to be confident and professional in giving speeches in their community, or leading public discussions. She gave speeches herself across the nation and a statue of her at a podium stands` in Washington D.C.

She was also able to take a grand tour of Europe and wrote articles about her experiences and sent them back to American newspapers. “She looked at how women lived in different countries and wanted to speak out,” explains Olsen.

Ever since Willard was young she knew she wanted to be a part of something. “The women she grew up with [such as wives of professors and ministers] tended to be involved in things. I think that influenced Frances greatly,” explains Olsen.

Evanston and the North suburbs used to be very Methodist towns. This included Northwestern, which was very engaged in the temperance movement. On the contrary, West Wilmette had a German population and drinking was a part of their culture. Prohibition began in Evanston.

“They [the WCTU] would try and persuade kids, as young as they could get, to take the pledge not to drink,” says Olsen.

The effort was used to deter crime and domestic violence. However, crime increased with illegal distribution of alcohol. Bribes were taken among political officials or policemen to look the other way, and even death rates increased because people were buying dangerous home brewed drinks.

Chicago has a history of its own with the nation’s most notorious gangster, Al Capone. Capone had a favorite hang out spot at The Green Mill, just about 12 miles from Evanston. The Green Mill has a hatch that leads to a series of underground tunnels where Capone made 60 million dollars a year on speakeasies and bootlegging liquor.

On Sheridan Rd. the shopping center Plaza Del Lago was once considered “No Man’s Land,” where young people could avoid the law and take part in dancing, listening to jazz, and illegal drinking.

Prohibition didn’t stick, but the tradition of illegal drinking carries on.

According to an article in the New York Times, college students under 21 are more likely to binge drink than those who are of legal age.

There are already efforts to lower the drinking age. Students for a Sensible Drug Policy have started a national online campaign.

“The government should lower the drinking age because in the eyes of the law, we are adults at 18,” says junior Simone Whiteley-Allen. “Meaning we should have the responsibility to drink like adults.”

There is also evidence that lowering the drinking age will lead to more injuries among youths. According to NPR, Boston University concluded that drunk driving is reduced when the drinking age remains at 21. No matter how society handles underage drinking, the problem remains.

Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.