Students recount experiences with mental health services

December 26, 2018

Trigger Warning: The following story contains information regarding mental health issues that may trigger some readers. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255.

Disclaimer: In this article, we write about the experiences of certain students who have faced mental health issues and their perspectives on the support systems that exist at ETHS. We recognize that we do not cover the range of mental health issues that exist among students. We have changed the *names of certain minors in order to protect their privacy. More information on mental health issues can be found by calling the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ hotline number at 800-950-6264.

Junior Lisa Johnson* was a freshman when she was first hospitalized for her mental health. In order to make up nearly a quarter’s worth of schoolwork, Lisa worked with the Pre/Post Hospitalization Program (the PHP).

According to the ETHS website, the PHP is one resource that the school provides to students making the transition back to school from hospitalization due to either mental health issues or pregnancy.

The PHP was established in efforts to strengthen communication between students, families and hospitals and to ultimately ease the transition back-to-school for hospitalized students. In 2012, a team of social workers, counselors, psychologists and teachers teamed up to create a proposal for the program. The proposal was officially passed by the school board in 2015.

“[The proposal] had to do with supporting the students who were currently being hospitalized, specifically making sure that we were streamlining the communication with hospitals,” Associate Principal of Student Services Taya Kinzie says. “We had inconsistency. We didn’t have a point person because we didn’t have the capacity for all the students.”

Before being named associate principal for student services in 2015, Kinzie worked as a social worker at ETHS and contributed to the process of creating the PHP. Lisa worked with the PHP until her freshman year ended. At the end of the year, she was no longer officially in the PHP, despite still being behind on work. Upon returning to school the next fall, Lisa found that she was on her own.

“I was sort of kicked out of the PHP. Once they decide that you don’t need their help anymore, they start transitioning you out,” Lisa explains. “I think one thing about being hospitalized or taken out of school for mental health issues is that it’s difficult for teachers, the school and students to understand that [mental illnesses] don’t go away like a broken wrist. The first time I was out of school, [it] took me months to get caught up.”

Senior PJ Woods* was hospitalized twice in 2016 and once in 2017. She also worked with the PHP when transitioning back into school. Similarly to Lisa, PJ felt as though the PHP staff members stopped working with her before she felt entirely adjusted back into school.

“Once you finish your work, they say ‘you don’t need to be here anymore,’ which is reasonable,” PJ says.

However, PJ explains that she felt as though the program failed to help students reach that point. She describes the program as having a message of “you should do your work,” instead of actually helping students complete missing assignments.

“You can’t miss eight classes and then be expected to be done in two weeks. If you are trying to get me to graduate on time, you need to be more patient with me and maybe help me make a schedule for when I need to come [to the PHP room],” PJ says. “Maybe not like ‘it’s your fault for not coming.’ It’s not Wildkit Academy.”

Lisa was hospitalized again during her sophomore year and began working with the PHP staff members again upon her return to school.

“I had a more comfortable experience the second time,” Lisa says. “Partially because my parents were more pushy.”

Lisa says that her parents spoke with the PHP staff members about giving her guidance on how to catch up on her work.

She explains that the PHP staff members guided her through a specific program called “3, 2, 1.” In this program, students are transitioned out over three weeks. Lisa was allowed three check-ins during the first week, two during the second and one during the third. She notes that she found the “3, 2, 1” system to be effective.

Still, Lisa says that once you’ve been transitioned out, the PHP is no longer a resource.

“I’ve walked back in just to say hi, and I felt like I was not welcome there.”Senior Sophie Stone* was hospitalized both her freshman and sophomore years. Both times, it took several months to fully transition back into school.

Sophie, similarly to Lisa and PJ, feels as though the PHP did not fully accommodate her needs. She explains that in addition to missing months worth of schoolwork, trying to regain stability and continuing to deal with mental illness makes it even harder to get back on track.

It was not just the workload that Sophie struggled with; obtaining a 504 plan and “Incompletes” also complicated the process of transitioning back into school.

A 504 plan is used to ensure that a student with a disability identified under the law receives accommodations in school. According to the Illinois State Board of Education, they are available to a person aged 3-22 who lives with a diagnosed disability, “which is defined as a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.”

“It took 10 months and two hospital inpatients to get one,” Sophie says, commenting on her own experience obtaining a 504 plan. “Even after the inpatients, it took a few extra months.”

Sophie got denied a 504 plan in her first attempt at obtaining one.

Obtaining an IEP (Individualized Education Program) fosters similar struggles. While a 504 plan comes from the 504 section of the Rehabilitation Act and was created to prevent discrimination on the basis of disability, an IEP, as specificed by the special education law — Individuals With Disabilities Education Act — is for students with disabilities. Both IEPs and 504 plans act as blueprints of specialized learning plans for students.

Incompletes essentially grant students extra time to complete schoolwork in a certain course if deemed necessary by counselors, department heads and teachers collectively.

Sophie explains that she tried to get Incompletes for some of her classes, as she had many missing assignments, but was denied them because she was not “technically failing.” She eventually was able to obtain an Incomplete for one of her classes.

Of the four students who went through the PHP and spoke to The Evanstonian, all four reported similar concerns regarding their experience. The four students expressed that they felt overwhelmed upon their return to school and that they felt that the PHP staff did not provide sufficient support. The PHP clinician Martha Zarate-Ortega and the PHP paraprofessional Joanna Goodson both declined several requests for interviews.

Students in the PHP are also invited to participate in the Bridge Program, which acts as a counseling group for students who have missed school due to hospitalization. Unlike the PHP, the Bridge Program is run entirely through the school. Students spend one period a week meeting with other students transitioning back into school.

“Bridge gave me a voice,” PJ says. “It made me feel like I wasn’t just a six digit number.”

Lisa, who still attends Bridge meetings, has vocalized appreciation for the student-led meetings as well.

“I’ve made a lot of friends through Bridge,” she says. “It’s a big support system.”

While the PHP and Bridge accommodate solely to students who have been hospitalized, social workers, psychologists and counselors are available to all students.

By Rachel Krumholz, Ben Baker-Katz

Executive, In-Depth Editors***

While schools across the country are working towards destigmatizing mental health, the misconception that mental health does not impact academic performance persists, even within the walls of ETHS.

“The stigma that mental health is completely unrelated to your performance in other arenas of life, especially academics is pretty present,” senior Caelen Behm says.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, one in five American teenagers ages 13-18 are currently living with a mental health condition that impacts their academic performance. This means that in a class of 20 students, four of them may need special accommodations or additional support.

The increasing amount of diagnoses has prompted an increase in conversation around how ETHS teachers and administrators can support students’ mental health within a classroom setting.

“How well a kid does in school is not just based upon their grades, but also their well-being as a person,” biology teacher Beth Christiansen says. “If they’re not comfortable and feel safe and secure, that’s going to impact them many ways, and it may impact them academically.”

Christiansen feels that it’s part of her responsibility as a teacher to check in with her students if she notices something seems a little off. If a student seems to be struggling with something, Christiansen will talk to the individual, their parents, or a social worker or psychologist in the building.

Director of Student Support Services Dondelayo White works with students who suffer from mental health concerns on a daily basis and is in agreement with Christiansen that mental health has a considerable impact on students within the classroom.

“It’s easy to say ‘leave your problems at the door’ or ‘don’t bring your problems with you’ but when we think about educating the whole child, I think we have to look at all aspects of the whole child,” White says. “It’s not just about academics. It’s also about how a student feels or how he or she shows up.”One of White’s jobs at ETHS is managing 504 plans. Whether or not a 504 plan is necessary for a student is determined by White and the rest of the student’s grade-level team. This team, comprised of teachers, a student’s counselor, dean, grade level social worker and psychologist, looks at three criteria to determine whether or not a student needs a 504 plan.

Teachers are informed of a student’s 504 plan and IEP accommodations at the beginning of the school year and can view the details regarding them through the Teacher Access Center (TAC) at any time. If teachers have questions about a student’s accommodations, they are referred to a student’s case manager: a special education teacher who usually communicates and checks-in with students who have 504 plans and IEPs. White says that although there have been instances where teachers have questions about a 504 plan, she has never encountered any problems with teachers not following accommodations or being resistant to them.

Some students with a 504 plan or IEP administered for mental health concerns have had mixed experiences with how their teachers respond to their accommodations.

Lisa feels that while she has had positive experiences with some teachers in regards to her IEP, many of her teachers have not been very supportive or cooperative. Lisa says that she has had experiences where teachers were passive aggressive or resistant to her use of her accommodations.

Salvador Zepeda, an IEP case manager and special education teacher, says that the dissonance between the student, their IEP and the teachers could be improved with better communication among teachers, case managers and students.

PJ has also had mixed experiences with her teachers in regards to her IEP. While she has found some teachers to be very accommodating, others were more naive and provided triggering material in class without warning, something she felt was damaging to her mental health.

Though she does not feel that it is a teacher’s primary job to be there for students emotionally, PJ feels teachers should have specific training to help students with mental health issues they may be experiencing.

“They have a training for everything else, might as well teach them how to deal with a kid having a panic attack or something,” PJ says.

Teachers do receive trainings on supporting physical and social or emotional issues that commonly affect students.

“In terms of mental health, school-wide, that’s something we are leaning more towards,” Zepeda says.

ETHS is working to further support students’ mental health in the classroom. Anyone suffering from any mental health concerns, whether or not they have a 504 plan or IEP, are urged to reach out to school support team.

Kinzie explained that ETHS is always working towards improving the mental health services at ETHS, especially in regards to changing the perception of mental health as a whole.

“Mental health tends to be pathologized as depression and anxiety as only internalizing, rather than depression and anxiety actually as externalizing as well,” Kinzie says. “Clinical definitions of depression in adolescents include agitation, include anger, include frustration, and I feel like we have come a long way as a school to embrace and support all students who may not be manifesting what society’s definition of depression is.”

She reiterated that her door is always open for students who have any questions, comments or concerns regarding the mental health services at ETHS.

By Caroline Jacobs

Assistant In-Depth Editor

***

Though Senior Izzy Williams* had seen an outside of school therapist since eighth grade, she came into high school struggling with her mental health without a diagnosis. One of the ways Izzy began talking about her mental health in school was through Erika’s Lighthouse, during her freshman year.

Erika’s Lighthouse is a support group and program for adolescent depression. Though there is no longer a club at ETHS, it’s still a running organization nationally. It’s working to prevent suicide and dismantle the stigma behind mental health. She then spoke with a psychologist intern in school. When speaking about her actual interactions with social workers in school, Izzy says, “I found that she [the grade level psychologist] was uniquely able to help in a way that my other therapists hadn’t because she works at the school.”

In addition to all-grade level mental health professionals, there are two social workers and one psychologist for each grade. There are many ways for a student to seek out a social worker and the department is trying to promote the message that social workers are available for all students to come and talk to. The main social worker offices are at E123 and provide walk-in services. Additionally, teachers and parents can refer their students to social workers if they deem it necessary.

“Teachers can make referrals for students, if they see any social or emotional concerns come up in the classroom,” says grade level social worker for the class of 2021, Lisa Roncone.

“They can make a referral and we will reach out to that student.”

Roncone notes that social workers attempt to schedule meetings with students during their free periods, as they don’t want to pull them out in the middle of class so to avoid discomfort among the students.

While ETHS is continually working to bridge the gap between students and social workers, numerous students have brought up some concerns about the department. Some students recognize that school social workers are not long-term therapy solutions.

“I think that kids who don’t have outside support aren’t going to find everything they need at ETHS,” senior Joa Lee says.

They may not be able to be a full time support system, but the social workers do have certain students they see frequently.

“Depending on their needs that looks like a set weekly meeting for a quarter or a semester,” Roncone says.

However individual students find that planning other meetings is a weak point in the social workers’ department. Caelen was part of the Erika’s Lighthouse support group, and she spoke with other students about their experiences with school social workers and psychologists.

“[The social work office is] thorough in that it’s open door and that they’re always open to talk to you and listen to your problem,” says Caelen. “The only thing I think that I’ve heard that isn’t very thorough was the follow-up.”

Caelen adds that this could be due to the individual experiences of whom she’s spoken with and that their issues may have not needed a follow up. The protocol for social workers is to plan another session.

“Sometimes it will be situational where a student will just say, ‘ I’m good’ and ‘I can come down on an as needed basis.’ In other situations, if outside or private therapy is needed, then we make referrals,” says Roncone.

After meeting for awhile, students may extend beyond school resources.

“Social workers are frequently working with students’ families to secure the supportive services they need,” Megan Callahan Sherman PHD, MSW, LCSW amd professor of social work at Georgian Court University said. “Social workers are also resource brokers. This means they work to identify the needs of students and families and provide linkage to resources available in the community.”

Another therapy resource at ETHS is the Bridges program, which is not affiliated with the Bridge Program. This is essentially a program that provides therapy for students at the school. The clinical social worker in charge of the program, though she works at ETHS, is employed by NorthShore University Health System.

Clinical social worker Julie Portnoy provides therapy sessions for students Tuesday-Friday. According to Portnoy, “you can see a therapist five times until parental consent is needed. Medications always need [parental] consent, sometimes not when your 18.”

However, Portnoy can only see students whose insurance is accepted by NorthShore University Health System.

Other options students who have regular meetings is to attend support groups led by mental health professionals at ETHS.

For instance, “If there is continued struggles with anxiety, there are groups. I run a group that’s mainly for anxiety, making social connections,” Roncone says.

While some students have expressed concern about mental health services, the school want to emphasize that they are available if a student needs support.

“Being in high school is hard,” says Roncone. “Everybody could benefit from talking to someone.”

By Lauren Dain, Sydney Ter Molen

Staff Writers

Mental Health Board receiving zero cuts after a proposed loss of 30 percent

In a research study collected last spring Mental Health Board of Evanston chair Jessica Sales said Mental was the number one problem in evanston followed by violence and obesity.

However, in September when the 2019 Evanston Budget plan was proposed, the Mental Health Board was projected to receive a 30 percent budget cut to accommodate Evanston’s seven million dollar deficit. When the 2019 budget was finalized on November 19, zero cuts were made.

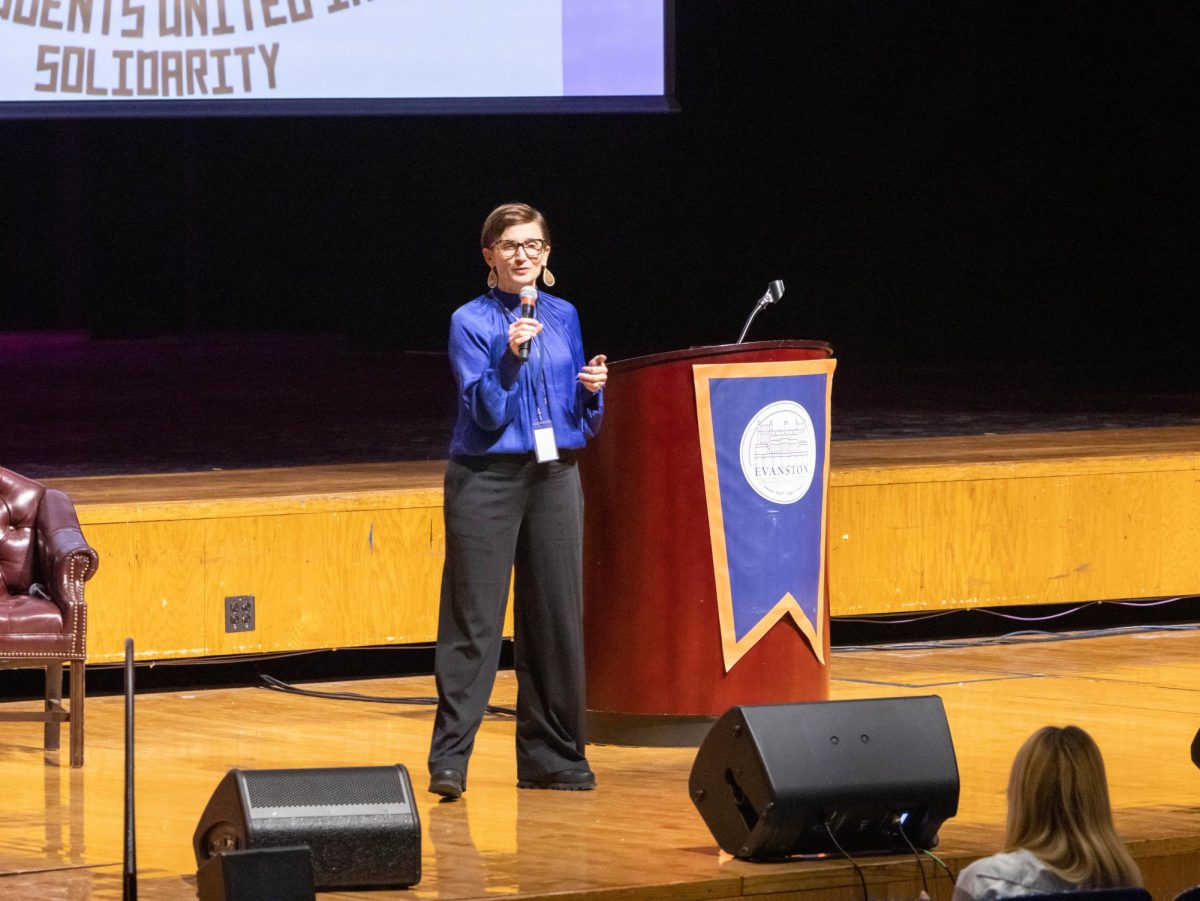

“Due to public support and the work of many local organizations and movements, the Mental Health Board budget for 2019 has been fully restored. The total amount to be allocated for next year is 736,373 dollars,” Sales said.

The board allocates money to local service agencies and nonprofits, the loss of 250,000 dollars would have affected Evanston based organizations that depend on the board’s money.

“It’s approximately 20 different agencies,” Sales says, “When you are talking about a 250,000 dollar decrease with very little warning, it doesn’t give the board time to allow local agencies to prepare for a reduction in their funding.”

Organizations that the board funds include Y.O.U, Family Focus and the James B. Moran center. These agencies are focused on teen and child services which lack of funding could have specifically affected ETHS students who attend them.

There were three special city council meetings which discussed the budget and where residents expressed concerns about what the ramifications could be to Evanston’s health services. “That’s probably why the funding amount is as great as it is because the city heard that and recognize the great work that (the agencies) do,” Sales says to the Daily Northwestern.

By Lauren Dain

Staff Writer