Your donation will support the student journalists of the Evanstonian. We are planning a big trip to the Journalism Educators Association conference in Philadelphia in November 2023, and any support will go towards making that trip a reality. Contributions will appear as a charge from SNOSite. Donations are NOT tax-deductible.

‘White frames of reference, “white is right” conclusions’: How integrating Evanston’s District 65 divided the city

January 28, 2022

Amidst a national movement surrounding integration, there was Evanston, a community at the forefront of the discussion, facing political and social roadblocks in the efforts to radically change the city’s approach to education.

Editor’s note: There are quotes in this section that feature people utilizing the term ‘negro,’ which is an outdated term with a long history of being used by racists to harm Black people. The Evanstonian has kept the term in these quotes to preserve the accuracy of how people spoke during the 1960s but do not condone the use of that term in any way.

Gregory Coffin. A name that was once synonymous with hope, with a bright future for our kids—a nationally renowned educator singled out for his success. That name has now slipped away into obscurity. How did the shift from the only educator featured in Who’s Who in America to a name you can only find in old newspaper archives occur? And more specifically, why did it happen in Evanston?

The more a person looks into Evanston’s history, themes will begin to reappear. One event which provides a direct parallel to the way Evanston’s climate around race is often discussed in the modern day is the story of Coffin. Evanston’s call for political change, followed by its swift rejection of radical integration in the three years between 1966 and 1969, was described by civil rights leader Al Raby as a desire to “talk about integration, not to act,” according to the North Shore Examiner in April 1970. This phrase is strikingly similar to many of the criticisms brought against Evanston’s race policies today—a superficial desire for apparent diversity while rejecting any change that could be seen as ‘disruptive.’

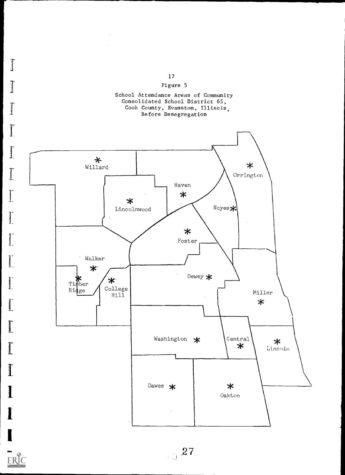

In 1960, the student population of District 65 was made up of 11,000 students spread over 15 elementary schools and four middle schools. In total, 22 percent of the district was made up of Black students, yet the number of Black students in each school varied greatly. Both Dewey and Foster schools, which had predominantly Black student bodies, suffered from overcrowding. The frustration over the treatment of Black students prompted a drive for integration, but what at first appeared to be an ideal solution would eventually spark large amounts of conflict.

By 1963, the school board implemented the Voluntary Transfer Program to relieve overcrowding within schools. The program allowed students to opt into being bused from Foster and Dewey schools to majority white schools. D65 officials hoped this would kill two birds with one stone—moving forward with integration at the same time as reducing overcrowding. They saw shocking success. Just three years after the program began, 450 Black students had been transferred into schools across Evanston.

To some families, though, the Voluntary Transfer Program did not seem like a drastic enough step to alter pre-existing segregation. Ten years after Brown v. Board of Education, the time seemed right for a fully integrated school system. So, in the wake of these calls for action, in 1964, the board adopted a resolution with the intention of completely integrating District 65 schools.

The integration plan was developed by the newly formed Citizen Advisory Committee made up of Evanstonians from a variety of backgrounds. Computers were utilized, and the staff from the Illinois Institute of Technology worked to redraw attendance boundaries for schools, as per the approval of the Committee, distributing younger children across the city. The intention behind computer utilization was prioritizing effectiveness and efficiency that only computers, at the time, could provide, given the extent of time and effort necessitated for manual redistricting. The new attendance maps would finally remove the status of de facto segregation in District 65. All schools would, from then forward, be expected to have between a 17-25 percent Black student body.

Coffin was hired as superintendent specifically to execute this plan. Before entering the Evanston scene, he had already defined his career around integration. As the superintendent of the all-white school system of Darien, Conn., Coffin stirred up controversy around a teacher exchange program that traded white Darien faculty for Black and brown faculty from New York City.

Coffin explained to the Chicago Tribune in 1966 that, “There is a moral obligation on the part of people who live in suburban areas and earn their livings in cities to be active in solving the race problem,” and that “Schools are supposed to shape society, not reflect it. School systems should take the initiative in unpopular issues.”

This moral desire for change seems to be the only reason Coffin would have left his Darien position for one in Evanston. He exchanged his job in a 5,000-pupil system with a salary of $25,000 for a system with 17 times the amount of students and a raise of only around $4,000 a year. But, the ability to work with a much larger and ethnically diverse population allowed Coffin to expand integration in a variety of ways, and, working closely with the Citizen Advisory Committee, that’s exactly what he did.

Coffin initiated a program focused on psychological integration; rather than simply meshing children of different races in the same classroom, he wanted to create schools that fostered racial acceptance. He created teacher training programs focused on cultural bias, empowering Black educators, and even went so far as to create curricula centered around Black history, something which even today is grossly underrepresented in the classroom.

Mary Barr, a former D65 student from the late 60s to the early 70s and author of Friends Disappear, a book outlining the history of race in Evanston, outlines her experience living through the implementation of these changes.

“I benefited from some of the changes that were happening at the time,” Barr says. “Coffin had really gone to great lengths to overhaul the curriculum in the elementary schools and District 65 junior highs. He had gone to great lengths to incorporate African American history and culture and really to train teachers to think differently about what they were teaching. So it didn’t just have to be like, ‘Okay, we’re going to learn about Martin Luther King.’”

Coffin’s pre-integration training program for teachers also took a shockingly modern approach to educational race reform, seeming comparable to much of the cultural competency training that teachers undergo in the present day (which, especially in Evanston, has been controversial). One 1969 Evanston Review article explained, “Summer seminars were held for faculty members, many of whom had spent years teaching in all-white or all-Black classrooms. Encouraged to discuss their own fears and prejudices, teachers were alerted to differences in cultural backgrounds and attitudes they would face.”

Coffin also initiated a review of textbooks to ensure the books represented the diversity of the students. He viewed the education system as a whole as a part of the white power structure, not just the ‘separate but equal’ schooling.

“[I]f you are not aware of the deeply embedded white racism which pervades the curricular materials used in schools throughout this country, thumb through a child’s school books, look at the illustrations, read some of the texts, not just the reading book, but the arithmetic word problems, the science book experiments, the history book heroes, the inventors, and discover it’s all white, not just white people, white situations, white institutions, white frames of reference, and ‘white is right’ conclusions,” Coffin said in a radio interview in 1967, just after his term began.

With these major changes, with issues of race and social justice at a fever pitch, Evanston began to receive a lot of press coverage. Nationally, Evanston was praised as an example of integration gone right. The same 1969 Evanston Review article shared, “Evanston has what many consider the nation’s most successful—and unusual—school integration program. Discussed in professional journals, scrutinized by national television, and emulated everywhere, it has drawn national praise as a model of how to go about achieving integrated education.”

The mood in Evanston as Coffin began his term was overwhelmingly positive. Families, both white and Black, were excited to be at the forefront of the integration movement.

“The reaction, overall, has been very favorable. We’ve had our opposition, and we know that there is still opposition. However, I sense there is a growing body of support for the total [integration] program, and I sense that part of this comes out of community pride. We’ve had very favorable publicity about the program,” Coffin stated.

One reason integration in Evanston was viewed as so extraordinary was because Evanston’s reputation at the time. In an interview in 1967, radio host Studs Turkel described Evanston as being known for its ‘rock-ribbed conservatism’ during an interview with Coffin, which refers to uncompromising traditionalism.

To that notion, the superintendent commented that Turkel’s perception of Evanston was dated.

“You have a stereotyped image of Evanston, which is not an accurate image,” Coffin said. “Evanston is changing. Evanston may be a rock-ribbed conservative kind of community, but this has not been my experience there. Evanston is a very proud community.”

“It’s quite heterogeneous,” Coffin said of Evanston. “It’s very proud, and it’s very anxious to solve its problems. It would like to solve its problems by itself without the state or the federal government or any outside of participation. And, so, I think one of the reasons I was invited to go to Evanston was because the people in Evanston felt that maybe I could help them solve its problem— which was a problem of rather tight de facto segregation.”

In practice, the integration plan that Coffin and the school board implemented solved this problem quite well. The easiest way to meet its diversity quota seemed to be sending Black kids to majority white schools. So in 1966, not even a year after his introduction as the superintendent, Coffin proposed a bussing plan that would commute Black students from Foster School, where they lived in the Fifth Ward, to other schools throughout Evanston. This meant that their schools were often miles away from where they lived. In exchange, white students were bussed into Foster School. But they weren’t bussed into Foster School as it had traditionally stood.

Within a year of Coffin’s tenure as superintendent, Foster School had been converted to a lab school, which accepted students from across the city, resulting in a majority white student body. The number of students being bussed across the city jumped from 450 Black students to a combined total of 1,960 Black and white students as the district shifted from a voluntary bussing program to a mandated one, according to A Report on School Desegregation In Nine Communities by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

The district worked diligently to create support for bussing within the community, as it felt communal desire for change would be the driving force of the integration process. According to a report made by Coffin titled How Evanston, Illinois Integrated all of its Schools, a survey sent out to parents at the very beginning of integration efforts showed the merit of the push, with 92 percent of parents responding in favor of the following question: “If the cost of integrated education is bussing, then I’m willing to have my child bussed.” This is in stark contrast to how public opinion would begin to function the deeper the district dove into its integration process.

Despite this strong push to integrate D65, Coffin quickly began losing the favor of the Evanston community—in large part due to attacks in the media. As public opinion swayed, many began to question whether Evanston really was changing—or rather, whether Evanston was ready for change. The criticisms of Coffin began with attacks on his personality, calling his direct manner of speaking abrasive, and his penchant to make national news “self-aggrandizing,” according to the Evanston Review in 1968.

Soon, though, attacks on Coffin became much more commonplace and much more varied. That same Evanston Review article explained, “Fearful white parents have told horror stories of Black pupils beating up or intimidating their children and complained that administrators have failed to move against rowdies.”

This is a statement that is not far off from many of the concerns a person may hear white families voice when considering sending their kids to more diverse schools today.

Other opponents, such as H. S. Sandler, overtly expressed their frustration with Coffin’s more drastic progressive changes, writing in the Evanston Review, “The colored citizens of Evanston have been here for many years, they do not live in ghettos, and the majority live in pleasant, well-kept surroundings. They always have had equal school opportunities in Evanston, with equal teacher qualifications.”

All of this was opposition that Coffin might have expected. Evanston’s layer of excitement and pride at its new diversity was peeling back to reveal those conservative roots about which Coffin had been warned. However, another much more surprising group which took issue with Coffin’s methods was Black Evanston parents.

Despite initial excitement, when bussing plans had been in practice long enough, Black communities began to see a reality that wasn’t quite what they’d been promised. Children who lived within a mile of the school they were set to attend did not qualify for bussing, which forced parents to use their own money to rent buses for their children or get their students to school themselves. There was also no lunch program provided for children. At the time, schools didn’t have cafeterias; instead, children returned home to eat lunch. Kids not within walking distance of their homes were unable to go home for lunch, meaning they ate sack lunches in segregated rooms at card tables; this program was in place at five of the district’s schools.

Yet, parental concern was not echoed by the administration. One school board member stated, “I’m not in favor of sack lunches for everyone. The fact that some children have no adequate supervision at home at noon is a personal problem, not a district concern. The fact that the five school lunch programs will be segregated should have been thought of when we considered breaking up boundaries.”

The impact of integration on Evanston children and the community was significant. The increasing levels of integration across the city resulted in white flight out of certain areas of the city as well as out of Evanston entirely, which caused the student population to decrease drastically and discouraged many who had originally purported integration. Within integrated schools themselves, Black students were scoring at higher levels than they had during segregation but still below the national average. Black children, in many cases, felt academically overshadowed by white students due to the limited resources that their schools had been given in comparison to the white schools when D65 had been segregated. Those accessibility issues lessened the benefits of integration, according to the same Report on School Desegregation In Nine Communities.

Despite Coffin’s efforts to initiate an accepting community, self segregation was pervasive in schools. One middle school teacher described the status of integration as “good racial interaction, though, generally, you will find that 80 percent of the Blacks and 80 percent of the whites prefer to stay to themselves while 20 percent will intermingle. Often, children who relate well during the year are negatively influenced over the summer by parents and others.”

Barr wrote that “Integration really came at the expense of Black children. Black children lost their neighborhood school. They lost Foster School. They went to school with white children, but they continued to be alienated. Bussing made it really difficult for them to become an integral part of the school they had to leave. As soon as the bell rang, at the end of the day, they had to hop on the bus and go back to their neighborhoods. They weren’t really able to participate in after-school programming. And they weren’t really able to just hang out and play with their friends. Again, they had to leave pretty much right away.”

Often, children who relate well during the year are negatively influenced over the summer by parents and others.

— District 65 middle school teacher

On top of the bussing issue, Black families continued to see the threads of racism within the integrated school system. Despite the district receiving a federal grant of $123,000 for pre-integration training under the Civil Rights Act and $58,096 in funds for examining curricular materials for prejudicial treatment of minority racial and ethnic groups, the levels of disciplinary action against Black students increased after these programs were put in place, according to the Report on School Desegregation In Nine Communities. This angered many parents, furthering the rift dividing the district, administration and families.

The community’s division over all of these issues mounted, with news beginning to vilify Coffin much more consistently. The final straws for angered families came towards the end of 1968, when two major controversies caused contention around Coffin. The first issue was a report released by the Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction criticizing Coffin’s newly appointed instructors—specifically the Black ones. According to Mary Barr, the report claimed that “five Evanston principals lacked “supervisory certificates.” Despite four of the five having master’s degrees and all of them being enrolled in state regulation compliant certification programs. They also accused the district of illegally using teachers’ aids to conduct classes, despite the fact that the aids were used to help one or two children or chaperone children on buses. Notably, many of these aides were Black.

But perhaps the most important ‘evidence’ against Coffin was an unpublished study—ultimately not published due to unreliable methodology—funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, which showed a decrease in test scores between 1967 and 1968. The exam used to collect this data was questionable, since its materials seemed almost completely unrelated to what children were learning in schools. Nevertheless, the conclusion people drew from D65’s attempt to integrate was that it resulted in a decrease in the quality of education. Families—especially white families—were terrified for their children’s future, a reaction that mirrors ones we can see today.

In the wake of these events, and to much community protest, the D65 school board made the decision to extend Coffin’s contract for only one year more—essentially meaning he would be out of a job at the end of the year.

Coffin wouldn’t go out that easily though. As soon as the school board’s decision was made, community uproar shook the city. Board members were protested in the streets, pro-Coffin letters filled newspaper columns, and a variety of activist groups expressed their displeasure with Coffin’s impending removal.

A Chicago Tribune article described the climate.

“Evanstonians, you see, like to devote Sunday to protesting for or against Supt. Gregory Coffin, whom the school board seeks to depose. There is a pro-Coffin faction called Citizens for Coffin and an anti-Coffin group called the Community Education Committee.”

There was certainly clear division amongst the two types of protesters. The anti-Coffin supporters were aligned with the wealthier, much more conservative side of Evanston, while the pro-Coffin side favored Black and brown Evanstonians. Despite their displeasure with D65’s bussing, Black Evanstonians mostly agreed that Coffin’s vision for integration was one of the best there was. He became a symbol for Evanston’s desegregation—and his removal seemed to be synonymous with the success of anti-integration sentiment. As Barr wrote in Friends Disappear, “The main issue was not Gregory Coffin’s contract; it was high-quality integrated education.”

The protests were so widespread that, eventually, the board made the decision to push back the finalization of Coffin’s removal. It would be after the next election of school board members, so if pro-Coffin candidates were successfully elected, he wouldn’t be removed. Essentially, it came down to the ballot box. If Evanstonians came out and supported school board candidates that backed Coffin, he would stay, and if not, he would be replaced.

Votes were cast, ballots were counted, and, at the end of the night, Coffin had lost. After a groundbreaking turnout, there was a 51 percent margin in favor of anti-Coffin candidates. The community had spoken; the will for integration had come and gone, and, already, the school board began its search for a replacement.

White liberals will be able to see themselves in the mirror. They’ll recognize the contradictions in their political philosophy, their vacillation and lack of personal risk-taking commitment and, most of all, their ambivalence about integration. — Gregory Coffin, former District 65 superintendent

The Coffin saga remains prescient in its depiction of what Evanston is about—both on the surface and below.

“I feel like it’s a really unique and unusual place in that it’s this wealthy suburb that has a large African American population,” Barr says. “I mean, you just don’t find that anywhere else.”

Evanston seems to be constantly caught up in an identity crisis. It’s part suburb, part city; part diversity and part de facto segregation. Its desire for change—its desire to become the face of change—is constantly juxtaposed with that ‘rock-ribbed conservatism’ which runs much deeper than many Evanstonians think. So many of the arguments against Coffin and his policies are echoed in the city’s modern political scene.

In his Chicago Tribune review of a book about why integration fails, Coffin provides a commentary on his strange experience in almost-suburbia, saying that in this book on the failures of integration, “White liberals will be able to see themselves in the mirror. They’ll recognize the contradictions in their political philosophy, their vacillation and lack of personal risk-taking commitment and, most of all, their ambivalence about integration.”