More than just a shirt: an examination of the harmful connotations of our fashion industry

November 8, 2019

A few weeks ago on the 2019 New York Fashion Week runway, American fashion brand Bstroy displayed a sequence of hoodies representing Sandy Hook, Columbine, Virginia Tech and Stoneman Douglas—four of the deadliest school shootings in America. The hoodies had holes representing bullets that took the lives of students, and is just one example of fashion companies producing offensive designs.

“With all the stuff that is happening in the world right now, I feel like companies have to be more aware with what they are doing and what they are putting out,” says sophomore Maggie Irving. “It’s just not fair to everyone that is seeing their products and just unfair to all the things that they are bringing ‘awareness’ to. I feel like [the fashion industry is] a part of the problem because there are already so many bad things happening.”

Fashion, as seen on the 2019 New York Fashion Week runway, can be a means of human expression, but can also be a way to convey a larger sociopolitical perspective. The retail industry has even been named the third largest in America behind business services and the food and restaurant industry, according to Guidant Financial. However, when brands produce designs that can be perceived as offensive, the conversations around those products become more controversial.

Students in Evanston recognize that fashion brands have taken steps too far. While a company may intend to create a design that provokes thought or enjoyment, the offensive implications of the design may initially go unnoticed.

“I think that there is always some sort of romanticization around tragic events and a Columbine sweatshirt. I personally think that that sweatshirt just does not look like it is paying any tribute,” says junior Noam Hasak-Lowy. “I think there are ways to have pieces that memorialize tragic events, but a grey sweatshirt with ‘Columbine’ written across it just does not look like one of those.”

Shortly after these designs were posted on Instagram, many people objected to their intentions. The general theme of the comments were that viewers were outraged. Viewers then expressed opinions on how they had been personally affected by the shootings. American fashion brand Urban Outfitters also displayed a piece that sparked a debate between the company and consumers.

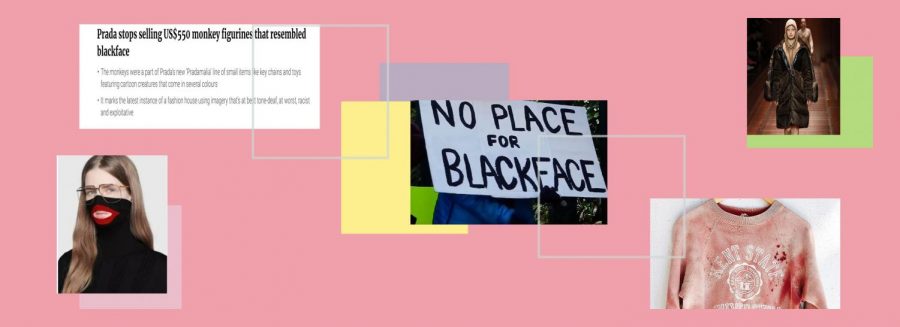

In Sept. 2014, Urban Outfitters released a distressed and worn out looking sweatshirt with “Kent University” written across the front. The discoloration throughout the fabric led shoppers to realize that they were faux bloodstains. Many angry tweets followed the release of this sweatshirt. “@UrbanOutfitters is pure garbage: selling a kent state sweatshirt w/ blood spatter” said Twitter user @BeccaLaurie. In response to comments like this, Urban Outfitters later removed all of these sweatshirts from their shelves and issued an apology over Twitter, which stated: “There is no blood on this shirt nor has this item been altered in any way. The red stains are discoloration from the original shade of the shirtand the holes are from natural wear and fray.”

Kent State University then issued a public response to Urban Outfitters expressing how they took “great offense” to this sweatshirt.

“I think that they probably thought that it had the right intentions and that it was a positive statement,” senior Audrey Kermgard says while looking at the Urban Outfitters sweatshirt. “They [Urban Outfitters] thought that people would buy it because they wanted to make a statement, but it wasn’t sensitive.” However, luxury companies have not only tried to profit off of school shooting. Some brands have recently marketed products depicting blackface.

During Black History Month in 2018, Italian luxury fashion brand Gucci released an $890 jumper. The jumper was all black and pulled up over the model’s mouth with big red lips, depicting blackface. Many shoppers were outraged and offended when seeing this piece and attacked Gucci. Shortly after, the company issued an apology on their website and removed the sweater from their shelves.

“I don’t know what [Gucci’s] purpose was when making that,” senior Kijuan White says while looking at the Gucci sweater. “They obviously had to know that that was going to be offensive to the black community.”

One reason the sweater was offensive is because of the history of blackface. Blackface started in the 1830s in New York before The Civil War. Performers, usually white, played black “characters” in minstrel shows in which they painted their faces with shoe polish or burnt cork to mock and dehumanize African Americans for white entertainment. The exact origin of blackface is unknown; however, it dates back to European theatre productions and Shakespeare’s Othello.

Thomas Dartmouth Rice was arguably the most well known blackface performer and is considered the “Father of Minstrelsy.” Rice created a blackface stage “character” named “Jim Crow” after traveling to the south to observe slaves. The name of this character would eventually denote a system of legalized segregation.

However, Gucci is not the only fashion brand to have created blackface products and to miss the historical significance of those designs. In Dec. 2018, Italian fashion brand Prada designed figurines that were all black with red lips resembling blackface, which sold for $550. One reason companies like Gucci and Prada may have produced pieces like these could be due to the lack of a diverse staff and varying opinions.

“Often in fashion, diversity is superficial, like the casting of different races of people on the runway or in campaigns, while the designers and executives calling the shots behind the scenes remain unchanged — and not reflective of the consumers a brand is trying to attract,’’ says Chantal Fernandez, a writer from Business of Fashion, in an article reflecting on the corruption in the fashion industry.

In order to honor different perspectives and opinions, companies may consider increasing their communication and working to diversify the fashion industry.

“[The fashion industry] could have meetings with all the workers and discuss the products that they are going to put out,” says White.