What I wish I knew before “coming out”

April 26, 2019

Content Warning: This article discusses experiences surrounding anti-queerness and includes an explicit word.

You know when you’re feeling yourself? Music blasting, makeup on, looking flee. You dance around your room and maybe look in the mirror. On days like these, it’s not that my skin cleared up or I suddenly got thiccer. I still have my insecurities; I just feel more like myself. Be that because of the clothes I’m wearing or the people I am around, I’m a little bit more me. There is a strength I feel in those days: a level of pride that no commercialized parade can create.

It was a Friday. I had just finished up the second day of the SOAR conference and shooting photos with dope people. I was thriving. My headphones were in and a queer legend was playing: Frank Ocean. I danced up the stairs, took my shoes off and stumbled into my apartment. My music was blaring loud enough so that I couldn’t hear the wooden floors creak under my weight or my brother’s voice on the phone. Taking my headphones off, I entered his room to say what’s up? I could still hear Frank Ocean’s queer voice fill the space so I paused the music. Heteronormativity creeps in. He scans me — examining my clothes, my makeup, my hair — he says: “What the f— are you doing to yourself?”

I entered the bathroom. I look at myself in the mirror. What does he mean “what the f— are you doing to yourself?” This is myself. Nevertheless, I pull out a makeup wipe from my cabinet. I continue to look into my eyes, seeing the sadness residing in them. I know I shouldn’t be doing this. I took off my eyeshadow. Turning the wipe into a rainbow, I stripped myself of my queerness. Next, my eyes flicker to my short hair. What were you thinking shaving this? Finally, I peeled my layers of clothing off my body and put on something new: someone new. I look back into my eyes. I see the tears running down my stoic face.

Is this who you want me to be?

I go into my bedroom. The tears now dried up, but new ones pool in my eyes. I pull out a pen and paper. I write over and over again: what the f— are you doing to yourself? I needed to punish myself for being queer. What the f— are you doing to yourself? I needed to repent. What the f—- are you doing to yourself? My hand starts to shake and the letters become more and more illegible. What the f— are you doing to yourself? I reach the end of the page, ball up the paper and throw it away. I sit in destructive silence for a moment.

Taking a deep breath, I re-entered the bathroom. I put my makeup back on. I peel the costume I was wearing off and put me back on. My headphones slip on, over my beautifully shaved head. Opening up Spotify, I put Frank Ocean’s music back on: “Forrest Gump.” I look at myself in the mirror once more. A fresh smile comes across my face.

What the f— are you doing to yourself? Well, bro. This is my queer self.

Here’s the thing about my queerness; there was never a moment where I realized that I was queer. While the label itself came later, my sexuality and gender expression — although fluid — have never been a question in of themselves. They simply were. So, when I entered high school and removed the shackles of my catholic school education — where not only was my queerness stripped, but also demonized; labeled as temptation from the devil — one of the first things I did was search for a community to affirm my identities.

As a timid freshman, I entered these spaces hesitant. The anxiety in my chest would bubble as folks went around in a circle, introducing themselves. “Hi, my name is Trinity Collins, and I’m a gender and sexually deviant?” never seemed to cover it. I was met with, everytime, folks who I’m sure intended to be supportive. It’s okay to be questioning. It took me time to find my identity too. You’ll figure it out. This threw me. I didn’t know how to say, no you misunderstand, I am not questioning; I know who I am. I just prefer not to label it.

Rather than finding affirmation or solidarity in these spaces, I was met with an environment that made me question my identity in a way previously uncharted. Am I not gay enough? Is my gender expression not important? Is this a phase? For myself, initially, it felt as though a label was the entrance ticket into the LGBTQIA+ community, and I stood in these spaces without one. So, I forced myself to sidelines — ostracized from an already marginalized community. How was I able to truly claim this identity, this community, this oppression if I can’t even name it? So, I desparately searched for a label to introduce myself as — refusing to acknowledge the queer parts of my identity until they fit into a box validated by a confining acronoym.

There was a sense of immediate, shortlived relief when I stumbled across the word “queer.” It happened in my sociology class: a quick definition in the midst of a slide show. Queer. A beautiful umbrella term that provided space for the fluidity of my identity. The days when I liked a “whiteboy” or wanted to dress in a traditionally feminine manner wasn’t a betrayal of that label. My own identity wasn’t a betrayal of the label used to describe it. There was space to breathe. More than that though, it provide entrance into a community I needed to feel validated by.

I “came out” to my family a week later. I sat on the kitchen counter when two of my relatives started guessing various sexualities.

A relative goes, “I think you’re, what’s that new one called? Oh, asexual.”

And my brother responds, “I just tell everyone you’re probably bisexual.” They spoke in such a casual, nonchalant manner about my identity.

I looked at both of them with a quizzical face and go, “no. I’m queer.”

“I don’t know what that means,” the other relative said immediately. After questioning me, they pulled out their phone and said, “Hey siri: my [relative] just said she is queer — what does that mean?”

I got frustrated. I spent years figuring out a label that did not strip aspects of my identities from myself, yet, still allowed for other people to understand them. I know how much fear lies in the unknown. So, I figured using a conventional term would increase my safety level. While my family were not the first people I told, the impact of their confusion along with their importance in my life made it feel like the first time. Rather than confronting their ignorance, they used their confusion to call into question my identity or the validity of it.

So you haven’t decided yet? Maybe this is just a phase? Your look is just a big middle finger to your family. You know your sister’s friend started college straight, then was bi sophomore year and is now gay. You could end up a North Shore stay-at-home mom, for all you know.

I internalized the comments. The vocalization of dialogue that prior to “coming out” merely existed in my head reinforced my internal conflicts. Labelling my queerness did not eradicate the toxic heteronormativity or gender conformity within myself. I was still raised a woman. I was raised to get married to a man, have kids and become a stay-at-home wife. Subjectivity to the man is my prescribed purpose and being my queer is revolutionary in a patriarchal society. However, it is also compromising.

The parts of my queerness that can be perceived as adhering to the norm are affirmed whereas the majority of my queerness which increasingly cannot be disguised or misconstrued is denied or minimized. I pulled open my computer during work; my hands shook as I desperately searched for the news. A line was forming in front of the desk; clients waited to be checked out. I let out a sigh of relief. “I got into Northwestern,” I spoke out loud. I was surely in shock, misreading the words in front of me. My boss hugged me then I turned to check out the white man in front of me: “congrats. Oh, you’ll find a good husband there.”

Of course, my immediate reaction was out of anger. I didn’t know where to start. One, I don’t want to get married. Two, I’m queer. Three, I am not attending college to look for a SO [significant other]. Four, I’m at work and unable to yell at the man in front of me. However, swirling around with that anger was shame. Ashamed in the fact that I wasn’t planning on fulfilling my one, very clear role in society. I felt like I was sent the meme: “you had one job.”

Getting dressed in the morning becomes a game of who will win: my queerness or toxic gender norms. There are days when I would rather feel less like myself, and be accepted than feel like a walking exhibit. People pick and poke at my identity, hitting the tender spots that I am working on.

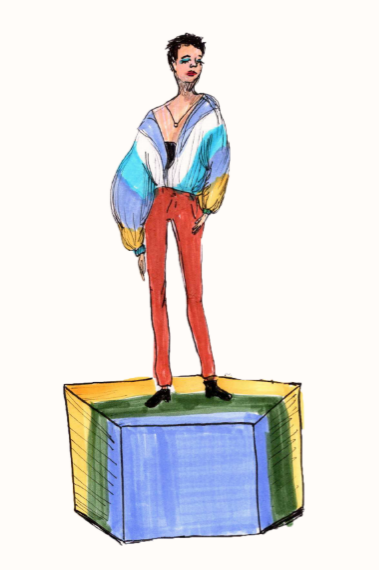

About two months ago, I entered my sister’s swim meet looking like I just rolled up out of Fresh Prince of Bel Air: windbreaker and patterned pants. I parked myself down on the ground and began to, not so patiently, wait for my sister’s heats to come up. My mom and her boyfriend wandered off.

My eyes were on my phone — scrolling through Instagram. The air was humid and I could smell the chlorine even over the metal in my nose. I started to feel self-conscious, like folks were watching me. I played with the collar on my jacket and readjusted my body position. My eyes flickered up for a moment to look for my mom. I saw a crowd of people formed around me. They kept a safe distance of five feet away — you know ‘cause those queers bite. They whispered and pointed, but no one approached.

I rose to my feet, head held high. The group took a step back. I could now clearly see the look of disgust on their faces so I masked mine with one of indifference. However, with the more time that passed, the anger rose to the surface, and the fear grew in their eyes. With a roll of mine, I walked away. They scurried out of my path, trying to avoid any possible physical contact.

As the night carried on, I became an interactive exhibit. Folks began asking me questions and pressuring others to try on my clothes. They spoke about my queerness as if they had any authority over it, me. Upon leaving, I searched for affirmation from my family that it was weird, scary even. However, all I was met with was a what do you expect?

There is a fear that follows my queerness; it looms overhead. I am able to often present myself within the norm when needed — especially when those around me attempt to rationalize my appearance or behavior through every avenue other than queerness. She wants to look like Twiggy. It’s just a girl crush; she’s envious. They’re really good friends. However, at times, conformity is not an option and safety is hardly ever guaranteed.

I was at a Christmas party this year, sitting at a kitchen table and nibbling on some cheese and crackers — bored out of my mind. Playing make-believe, a young girl, maybe eight or nine, came up to me.

Trinity“You’re under arrest.” I simply dismissed her, uninterested in the game that was transpiring. “You’re under arrest, get into the [dog] crate.”

My eyes widened in surprise. I was not entering that dog crate. Nevertheless, I decided to play along for the time being.

“Why am I being arrested? I have a right to know,” I said.

She paused for a moment, tapping her lips. Eventually a smirk creeped up, “You’re being arrested because you have a nose ring and a shaved head, and you’re a girl.” I rolled my eyes. The amount of gender rigidity young children express didn’t surprise me anymore. I began on my monotone pre-existing speech — “Gender as a Social Construct: Young Person Addition.”

However, she abruptly interrupted me. “NO!” she shouted. She opened a drawer and pulled out a knife. “You are going to jail.” She giggled a little and waved the knife at me, believing the entire situation to be amusing.

All I was experiencing was terror. You’re not safe. My voice became firm, “put that away and go to your mom.” She did as she was told.

I was shaking for the rest of the night. I know it was make-believe. I know it was a child. However, there are a multitude of narratives within the queer community of folks not leaving those situations unhurt. That is a reality — not my reality — but a reality of those who identify similarly.

I never truly “came out” for me. I “came out” because I began expressing my queerness without verbally defining it. Folks surrounding me took this as an excuse to define me for themselves — ignoring aspects of my humanity in the process. It was different; people went from just not knowing to telling me who I am. It was different. It felt different. My queerness could no longer exist in silence because silence meant it was being denied. So, I stopped being complacent and “came out.”

As a result, all my internal struggles manifest themselves externally. I have to confront my toxic heteronormativity and toxic gender conformity in every space I occupy because it’s the norm which I must protect myself from. Over the past six months, these external conflicts create new internal ones. The notions I hold surrounding my queerness fluctuate more so than they ever have. However, there is something about being forced to exist in an identity that is contested at every point. There is something about being pushed to the margins of society. There is something about being reduced to two tiny sections in your history textbook: AIDS and mental illness. There is something about the strength found in your history being taken from you. There is something about not knowing where you came from, about not learning that you stand on the backs of black transwomen. There is something about being erased. There’s an uncertainty that lies within what that “something” is and the way it appears, in the context of my holistic identity. However, I refuse to allow someone else to define what that “something” is. It is a part of my queerness, not a tool for others to regain power over my identity.

Tricia Tenpenny • Apr 28, 2019 at 12:14 pm

I applaud you for having the courage and strength to be true to yourself. Good luck!