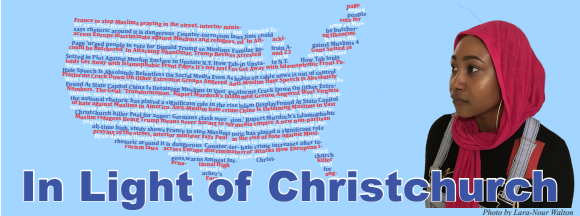

In light of Christchurch

Designed by Trinity Collins, Photo by Lara-Nour Walton

April 26, 2019

Trigger Warning: The following piece discusses matters of violence and hatred in regards to Islamophobia.

*Arabs and Muslims are not synonymous with one another and should not be conflated, but for the purpose of this article, we will be speaking about Muslim Arabs.

Every morning, junior Amné Djibrine peers up at Evanston Township High School’s brick studded facade and says a prayer. Once she passes through the main entrance doors, there is no telling what kind of harassment she will face.

Back in Chad, Djibrine had always been the center of attention. She’s loud and effervescent — the life of the party. But the attention that she’s received here in America has been less than desirable. In our very own H-hall, she’s been accused of being a terrorist; in the cafeteria, a boy taunted her to such an extent that she ripped off her hijab to prove that she wasn’t had hair.

“People treat us like animals, but we are human,” Djibrine explained tearily.

While xenophobic rhetoric has existed long before 9/11, the attacks on the Twin Towers led former President George Bush to launch a military mission he deemed a “War on Terrorism.”

The combination of Bush’s decision to deploy troops to Afghanistan and the nation’s rising fear of terrorism only bred propaganda regarding Muslims and extremism. This misconstruction of the Muslim community is still visible today.

The past few years, we have watched our president shamelessly spew Islamophobic rhetoric in front of an entire nation. In January of 2017, Donald Trump enacted the Muslim Ban which kept out refugees from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen, predominately Muslim countries.

On April 12, he shared a video on his Twitter attacking Minnesota Representative Ilhan Omar for speaking to the danger of generalizing all Muslims as terrorists. Her sentiments were given at the Council of American-Islamic Relations. Ironically, her speech was about upholding American ideals.

The scary thing is, America is on board.

Shortly after Trump shared the Islamophobic video, a Trump supporter was arrested for delivering death threats against Omar.

On March 22, The Washington Post released a study that found that “counties that hosted political rallies with Donald Trump as a headliner in 2016 saw a 226 percent increase in hate crimes over comparable counties that did not host such a rally in subsequent months.” The Southern Poverty Law Center reported to The New York Times that the number of white nationalist groups has increased by nearly 50 percent in 2018.

With a prominent figure constantly vocalizing and enacting an lslamophobic agenda, both hate speech and hate crimes are not only normalized, but encouraged.

Evanston isn’t immune to the nation’s effects. Our moral axiom is equally flawed. While xenophobic sentiments are often rebuked, and those who express them may be ostracized, Islamophobic comments seem to go unpunished. The day of 9/11 has given ample justification for anti-Muslim harrassment. Locally, Evanston can’t provide an adequate safe space for Muslims who have to endure daily provocation because of their religion.

In light of the Christchurch mosque shootings, we [Rachel and Lara-Nour] felt it was necessary to recognize both the prevalence of Islamophobia within our own community as well as honor the voices of those affected by it. We want to address our own positionality in regards to this piece.

I [Lara-Nour] identify as an Arab, Muslim woman. It pains me when the culprit of any violent act is Muslim because it enforces the stereotype that we are all intrinsically criminal. So, when I heard that the perpetrator of the Christchurch attack was Christian, I was relieved. But when I registered that the victims were Muslim, a tremendous sadness came over me. Having experienced and witnessed Islamaphobia, this shooting made me feel even more unsafe than before. I believe that we must bring attention to the plight of Muslims, as well as the unjust way we are portrayed in the media.

I [Rachel] identify as a white, Jewish woman. When I first found out about the Christchurch mosque shootings, I was undoubtedly angry, but also felt a sense of disconnection with what had happened. I have never experienced the negative repercussions of Islamophobia or racism. This article is an attempt to more so humanize the narratives I was able to hear.

The Christchurch, New Zealand shooting occurred on March 15 at two mosques. An alt-right white supremacist carried out an anti-Muslim terrorist attack that left 50 Muslims dead.

“When I found out, I couldn’t breathe,” Djibrine recalled her experience when she first learned about the Christchurch shooting. “My whole family was crying.”

Sophomore Lina Kodaimati, who discussed the massacre in her classes, had a discouraging experience; “I personally had a lot to say about the issue just because so many feelings needed to be let out.”

Growing up in a Syrian-Muslim family, Kodaimati has always grappled with the burden of her racial and religious identities. But during the discussion, it became clear to her that her classmates weren’t at all receptive to her plea to humanize Muslims.

“[My peers] were overlooking what I was speaking about because they don’t understand it. Do I completely blame them for that? No. But, I think that it’s a serious issue that fear controls people in a way that they’re not willing to listen and learn.”

This fear is a direct effect of 9/11 which resulted in the common misconception that Muslims are inherently nefarious and are only here in the U.S. to spread their anti-Western sentiments.

Yosra Yehia, history teacher, reports experiencing anti-Muslim aggression from the parent of one of her students. The parent, Yehia explains, emailed her with “concerns” regarding Yehia being the teacher of the World Religions unit.

“The parent was concerned that I was forcing her child into specific religious practices. I didn’t know what was happening. I was like ‘did this confuse you?’” Yehia recalls, pointing to her hijab.

Systematic dehumanization of POC communities in this country is exemplified by our census not representing the Muslim/Arab* demographic accurately, erroneously lumping the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) communities with the White category. Likewise, our standardized tests don’t reflect the presence of Muslim MENA individuals in school settings.

The MENA population is not acknowledged as part of the American population; neither their pasts as a POC community who have faced American oppression, nor their physical existences are recognized. In effect, their rich cultural histories are subject to erasure.

If Muslims aren’t even accurately and entirely recognized systematically, how are they supposed to be humanized in a social context?

Muslims are humans too, but it is the job of the government and the general public to find the humanity within themselves to guarantee Muslims safety and recognition.

As the Sufi mystic Rumi wrote, “Your task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.”