How hip-hop discusses safety and the criminalization of Blackness

December 16, 2022

Hip-hop has always had two very distinct ways of approaching social issues, lyrically speaking. The first is through sharp, observant and precisely crafted lines and songs. Take for example Chicago artist Saba’s song BUSY/SIRENS where he raps “Drawing they gun right off their hip/ I’m probably deservin’/ ‘Cause I know they serve and protect/ But they think I’m servin/Or they think my cellphone’s a weapon”, his downcast tone emphasizes his lyrics about police violence. Alternatively, 2Pac on his track “Changes”, penned, “There’s war in the streets and war in the Middle East/ Instead of war on poverty, they got a war on drugs/ So the police can bother me”. Two artists, on opposite sides of the country, twenty years apart. These lyrics are formed from musicians who have lived and seen the impact of things like police violence on their communities. The instrumentals are downcast, and reflective, spurring reflection on the words.

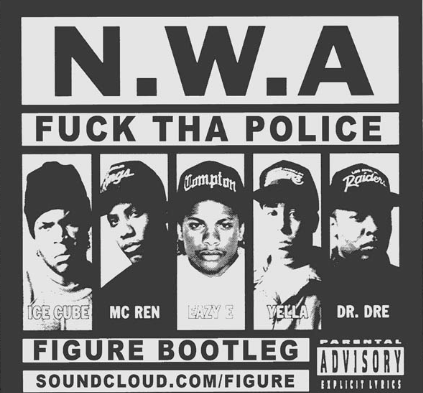

The latter approach is a bit different. Where the former was focused on painting a picture, this response is more about firing back. These are abrasive, brash, and unapologetic. It’s impossible not to mention N.W.A’s “Fuck Tha Police”, where Ice Cube raps “Beat a police outta shape/ and when I’m finished, bring the yellow tape”, or Vince Staples’ “Hands Up”, in which he raps, “Raidin’ homes without a warrant, shoot him first without a warning/And they expect respect and non-violence? I refuse the right to be silent”. Just as their counterparts who dissect the things they have seen, these artists react to what they have seen. Again, almost thirty years apart, the perspective through which they examine the problems is very similar. The anger is palpable, and seeps through the tense instrumentals behind the lyrics.

It’s within hip-hop’s disposition to combat the system. For as long as this country has existed, Black art has had a target on its back, especially if that art was deemed “radical” or “revolutionary”. In the 1920s, as Jazz came to popularity as an invigorating genre led by Black talents, the U.S government had schemes to stop it. In the 1930s, director Harry Anslinger of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics remarked that, “Their Satanic music, jazz and swing result from marijuana use” and that, “[Jazz] sounded ‘like the jungles in the dead of night.” Years later, Anslinger would lead the charge to arrest (and eventually murder) Billie Holiday, famous for her rendition of the anti-lynching anthem “Strange Fruit”.

Half a century later, in a cramped Bronx apartment, hip-hop was born. A product of Black exuberance and the dense New York borough, the music was a fresh new style. Less than a decade after its inception, these communities that fostered the genre, in its infancy at the time, became a target of the government. The (allegedly) CIA backed drug trade, and subsequent militant policing tactics unleashed as a “War on Drugs” ravaged these impoverished urban communities. The country changed as prison rates skyrocketed, and law enforcement became more hostile than ever.

Everyone knew that the system had changed for the worse. And as these conditions continued, the music began to reflect that. In 1988, N.W.A shocked the world with their record “Straight Outta Compton”. The album was a razor-sharp meditation on the poverty they had seen around them in a once-Black suburb destroyed by the government’s response to drugs. The driving force of this anti-establishment thesis was made clear on track three, the aforementioned “F*** Tha Police”.

Other artists knew the effects on their neighborhoods. Nas in the early ‘90s wrote “D’s on the roof tryna’, watch us and knock us/And even killer coppers, come through on helicopters”. Years later, on his gripping 2012 track “Reagan” (named in opposition of President Reagan who enacted the War on Drugs, and the importation of said drugs), Mike raps, “The end of the Reagan Era, I’m like ‘leven, twelve, or/ Old enough to understand that shit’d changed forever/ They declared a War on Drugs, like a war on terror/ But what it really did was let the police terrorize whoever”. The Reagan era ended around the end of the ‘80s. He finished his second term in 1989, five years before Nas wrote those lyrics. The catastrophic effects of the government’s tactics were blatant, and changed the way these neighborhoods—Nas in Queens and KM in Atlanta.

Of course, the scope of these issues is much broader. Some of these artists discuss more cyclical and personal traumas as a result of government policies that create disparate living conditions. Meek Mill’s 2018 song “Trauma”, for example, with the powerful line “and the judge got a hold on your father/go to school, bullet holes in the lockers”. Many artists have been put in jail under the pretense of their lyrics as evidence (amongst other malfeasances, such as coercing witness testimonies). The genre itself, as an outlet against the systematic issues that plague the communities of these artists, has always had a target on its back. Between people who characterize the music as violent or radical, and the government’s incessant attempts to convict the creators, the existence of hip-hop has always been a protest against the systems that try and destroy it. The musicians’ approaches to the unsafe conditions and the people who perpetrate them differ across areas and eras. Nevertheless, the music stays. It is impossible to ignore these issues and remain silent. The music speaks out, and against, the forces trying to stop it.

Saif • Dec 16, 2022 at 2:46 pm

I believe this is the most beautiful piece of writing I’ve ever read.