Opinion | Drawing the home that could be

February 22, 2021

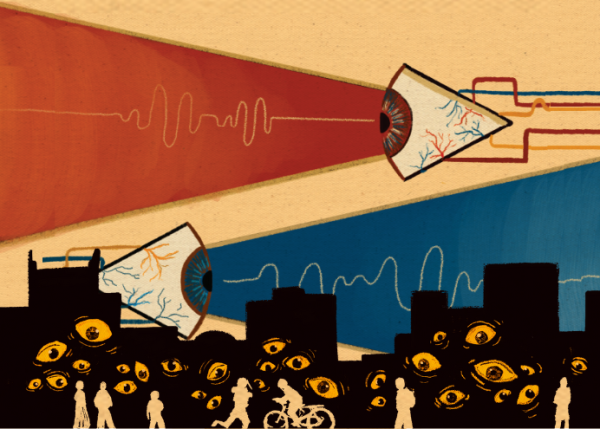

Drawing teachers, the good ones at least, will always tell you to see something, not just depict symbols and images—constructs—of what you believe you are looking at. It took continuous repetition of, “Just because you know what an eye looks like, that’s not what you see,” or something with a similar sentiment, for me to know what my mentors meant. It took even longer for me to understand that the act of seeing, and feeling truly seen for that matter, doesn’t just apply to visual art.

I believe that the first real identity, at least the first one I knew to be true, real and proud of, was as an artist. I entered the Evanstonian space as an illustrator, but it quickly became, and still is, the place I ran to when I didn’t want to go home, literally and figuratively; it became the place that I have simultaneously felt the least and most seen at ETHS.

As I began to write for the paper, though, I didn’t think twice about the stories I was assigned and how they reflected the student body. When considering the majority of whose stories were being told or what ideologies were constantly being pushed, published and praised, I tried not to wonder why.

I grew used to the assumption that I’d be covering the Black and Latinx summits, the notion that I was the social justice expert, the repeated question of ‘Why do you have to bring race into this?’ when I just wanted my peers to see something the way I did. I remember how cold the room grew when Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR) walked in for the first time. I can still hear the complacent and bitter wondering of ‘Why do we have to do this again?’

Whether it be my strong desire to assimilate with my white peers or my fear of being tagged as an “angry Black person,” I didn’t raise the question I was aching to know the answer to: why or how barely anyone I worked with, or wrote about, on the Evanstonian, looked like me?

Though I tried to compartmentalize how I navigated the Evanstonian space, my emotions could not. I recall walking home one day from a SOAR workshop. My face was hot, with angry tears streaming down my face because of this unanswerable question. I can’t remember what specifically sparked my frustration, but I remember that I seriously considered quitting the Evanstonian. Although I was still fairly new to the staff, I remember that, already, I was tired of being belittled; I was exhausted by the reality that I was one of the few Black or brown people on the paper. I was annoyed that rarely did people relate to the experiences of people of color at ETHS as I did. But, quitting wasn’t and still isn’t an option for me, at the least, I understood that. I understood that I would never “quit” being Black or Latinx; it wasn’t possible. It has taken a few meltdowns about why my eyes weren’t blue, but I couldn’t be more proud of my racial identity. I began to understand that, inevitably, I would experience racism in any institution that stood much larger than me, wherever I went. If it wasn’t in the Evanstonian, where I did feel pure joy as I wrote, interviewed and learned about people in my community, it would be somewhere else.

I quickly was secure in the fact that the Evanstonian was an activity I loved and should continue contributing to, but again I found myself at a crossroads: I could either leave it be and play a game that wasn’t created for me, or I could do everything humanly possible to reimagine that publication into space where I genuinely feel welcomed, heard and seen in the space. I chose the latter.

Still, I wonder what could have been, not if I decided to keep my foot in the open door, but what would have been if I never knew where the Evanstonian door was. Sometimes, even as an executive editor, I wonder what would have happened if I wasn’t nudged by my English teacher and then advisor for the Evanstonian, Patricia Delacruz, to illustrate. I wonder about all of the nudges that never happened during and before my time at ETHS because of the Evanstonian’s proximity to whiteness.

The Evanstonian has been the place I have felt most at home; it is also one of the spaces where I have felt most alone. For most of my time there and even still, the space may have been the place where I felt the safest in the entire school community, but often it would morph into a monster I had little experience fighting. The Evanstonian was the place where I first heard the word “tokenized” and “microaggression;” it was the first place in high school that I had felt those words in action; it was the first place where I personally understood what it felt like to be overpowered by a white, male presence. Simultaneously, the Evanstonian was the space that almost singularly helped me navigate ETHS. The Evanstonian motivated me to continue journalism after high school; it is the space that allowed me to discover my joy for people and storytelling.

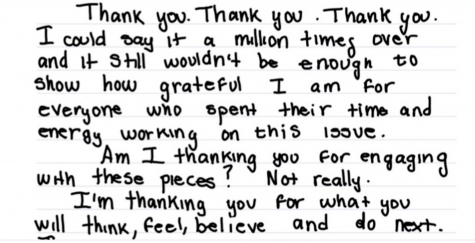

For the past four years, and especially after producing this issue, I can safely say that I was right about how I wasn’t alone in my constantly conflicting feelings about our paper—feelings that all boil down to the feeling genuinely seen and seeing myself consistently reflected in our publication. My feelings, at their core, are as straightforward as drawing has become for me.

In drawing, it’s all about seeing shapes and lines rather than ideas and perceptions. In journalism, it’s all about seeing individual people and complex experiences rather than entire communities and stereotyped narratives. Furthermore, it’s about giving said people an equitable opportunity to speak—a definitive platform to connect with the world as so many non-BIPOC are given since birth. In journalism, it’s seeing me as a complex human being rather than your token Black writer.

In this issue, after seeing every piece from start to finish, I know full well how much bravery and vulnerability writers were willing to compose to try to illustrate the complexities with race and the Evanstonian and how they intersect. For once, we all dared to see the paper—my home—for all that we are and all that we could be.